1796 United States presidential election

The Federalists coalesced behind Adams and the Democratic-Republicans supported Jefferson, but each party ran multiple candidates.

If there was a tie for first place or no person won a majority, the House of Representatives would hold a contingent election.

Republicans sought to associate Adams with the policies developed by fellow Federalist Alexander Hamilton during the Washington administration, which they declaimed were too much in favor of Great Britain and a centralized national government.

In foreign policy, Republicans denounced the Federalists over the Jay Treaty, which had established a temporary peace with Great Britain.

Federalists attacked Jefferson's moral character, alleging he was an atheist and that he had been a coward during the American Revolutionary War.

As a result, both parties ran multiple candidates for president, in hopes of keeping one of their opponents from being the runner-up.

The Federalists' nominee was John Adams of Massachusetts, the incumbent vice president and a leading voice during the Revolutionary period.

Adams's main running mate was Thomas Pinckney, a former governor of South Carolina who had negotiated the Treaty of San Lorenzo with Spain.

Pinckney agreed to run after the first choice of many party leaders, former governor Patrick Henry of Virginia, declined.

[6] The Democratic-Republicans united behind former secretary of state Thomas Jefferson, who had co-founded the party with James Madison and others in opposition to Hamilton's policies.

If no candidate won votes from a majority of the Electoral College, the House of Representatives would hold a contingent election to select the winner.

Additionally, there were rumors that Hamilton had coerced southern electors pledged to Jefferson to give their second vote to Pinckney in hope of electing him president instead of Adams.

If any two of the three Adams electors in Pennsylvania, Virginia, and North Carolina had voted with the rest of their states, it would have flipped the election.

(c) Those states that did choose electors by popular vote had widely varying restrictions on suffrage via property requirements.

Moreover, some states' returns have not survived to the present day, meaning that national popular vote totals in this article are necessarily incomplete.

John Quincy Adams and John C. Calhoun were later elected president and vice-president as political opponents, but they were both Democratic-Republicans, and while Andrew Johnson, Abraham Lincoln's second vice-president, was a Democrat, Lincoln ran on a combined National Union Party ticket in 1864, not as a strict Republican.

[22] The French foreign minister, Charles Delacroix, wrote that France "must raise up the [American] people and at the same time conceal the lever by which we do so… I propose… to send orders and instructions to our minister plenipotentiary at Philadelphia to use all means in his power to bring about a successful revolution, and [George] Washington's replacement.

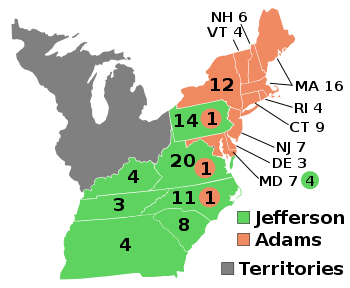

[24] The foreign intrigue France perpetrated was unsuccessful, as Adams won the election with an electoral vote count of 71–68.

A significant factor in thwarting the French efforts was George Washington's Farewell Address, which condemned foreign meddling in America.

[24] The Constitution, in Article II, Section 1, provided that the state legislatures should decide the manner in which their Electors were chosen.