1820 United States presidential election

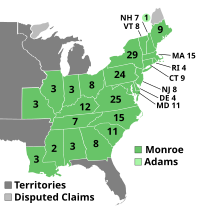

Taking place at the height of the Era of Good Feelings, the election saw incumbent Democratic-Republican President James Monroe win reelection without a major opponent.

Although able to field a nominee for vice president, the Federalists could not put forward a presidential candidate, leaving Monroe without organized opposition.

Nine different Federalists received electoral votes for vice president, but Tompkins won re-election by a large margin.

The nation had endured a widespread depression following the Panic of 1819 and momentous disagreement about the extension of slavery into the territories was taking center stage.

Nevertheless, James Monroe faced no opposition party or candidate in his re-election bid, although he did not receive all of the electoral votes (see below).

[5] Monroe's opposition to federal funds in constructing internal improvements and his apparent neutrality on the tariff issue were especially displeasing to Kentucky and the Middle Atlantic states.

In early 1819, the Kentucky Gazette vigorously endorsed the idea of federal internal improvements, condemning Monroe for his position on the issue.

Later, commenting on Monroe's pending visit to Lexington, the Kentucky Gazette said:[4] It is hoped the president will remain with us long enough to examine the state of our factories.

If their fallen state should produce any impression, it is possible, through the agency of the chief magistrate, that the government will take some steps to encourage domestic manufactures.After Monroe's visit, the Gazette, once more returning to the issue of internal improvements, noted that the President had been emphatically told during his stay in Kentucky that the people of the state were not in sympathy with his position on that question.

This conflict openly erupted after the Clintonians accused the Monroe administration of using patronage to defeat Clinton in his campaign for re-election.

When it came to the time of choosing electors, the Bucktail faction of the Democratic-Republicans, which was loyal to Monroe, and the Clintonians ran rival tickets.

The Panic of 1819, with its disastrous effects on many factories in the state, produced a strong demand for higher protective tariffs.

In 1820 the Aurora's anonymous correspondent, BRUTUS (suspected to be Duane himself), began to denounce Monroe as the champion of slavery, blamed him for causing the defeat of the tariff bill of 1820, blamed him for discouraging internal improvements, and accused him of championing the cause of the national bank, favoring the caucus system, and even encouraging the Supreme Court to render corrupt decisions.

The Democratic Press claimed that Monroe supporters were so numerous at the State House's Mayor's Court Room that the opposition had to move to Overholt's Tavern.

[4] The newly formed anti-Monroe ticket pledged support for Clinton as president and campaigned briefly in Philadelphia, though the rest of the state remained largely indifferent.

The Aurora vehemently attacked Monroe as a candidate who supported slavery and urged Pennsylvania to break from their vassalage to the "slave aristocracy."

On the eve of the election, BRUTUS (the anonymous source mentioned above) denounced Monroe as an enemy of internal improvements and domestic manufacturing, while praising Governor Clinton's support for these initiatives.

However, while Northern moderates urged Monroe to accept the compromise, Virginia Democratic-Republicans, led by the Richmond Enquirer, demanded that the South resist any restrictions on slavery in Missouri or other territories.

As such, the Virginia caucus was dismayed to hear rumors that Monroe supported a compromise allowing slavery in Missouri but prohibiting it in the Louisiana Territory above the Parallel 36°30′ north.

Virginians, including Henry St. George Tucker, wrote furious letters to Washington, condemning the compromise and expressing their unwillingness to support Monroe if it meant sacrificing Southern rights.

He wrote to his son-in-law, George Hay, emphasizing that principles were more important than expediency and suggesting that if the legislators preferred another candidate, they should say so.

Instead, the caucus reconvened on February 17 and nominated Monroe supporters for the electoral college, likely realizing their earlier mistake.

[4] On March 9, 1820, Congress had passed a law directing Missouri to hold a convention to form a constitution and a state government.

[11] While legend has it this was to ensure that George Washington would remain the only American president unanimously chosen by the Electoral College, that was not Plumer's goal.

Monroe's share of the electoral vote has not been exceeded by any candidate since, with the closest competition coming from Franklin D. Roosevelt's landslide 1936 victory.