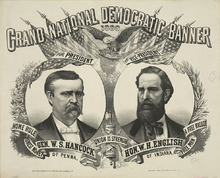

1880 Democratic National Convention

As the convention opened, some delegates favored Bayard, a conservative Senator, and some others supported Hancock, a career soldier and Civil War hero.

In 1876, Republican Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio defeated Democrat Samuel J. Tilden of New York in the most hotly contested election to that time in the nation's history.

[1] The results initially indicated a Democratic victory, but the electoral votes of several states were ardently disputed until mere days before the new president was to be inaugurated.

Monetary debate intensified as Congress effectively demonetized silver in 1873 and began redeeming greenbacks in gold by 1879, while limiting their circulation.

[9] Samuel Jones Tilden began his political career in the "Barnburner," or Free Soil, faction of the New York Democratic Party.

[12] Tilden initially cooperated with Tammany Hall, the New York City political machine of William "Boss" Tweed, but the two men soon became enemies.

[13] He formed a rival faction that captured control of the party and led the effort to uncover proof of Tammany's corruption and remove its men from office.

Congressional Democrats acquiesced in Hayes's election, but at a price: the new Republican president withdrew federal troops from Southern capitals after his inauguration.

[21] He considered many of his former friends (including Senator Thomas F. Bayard of Delaware) enemies now for their support of the Electoral Commission, and sought to keep the "fraud of '76" in the spotlight and burnish his own future candidacy by having his congressional allies investigate the events of the post-election maneuvering.

Tammany ran its new leader, "Honest" John Kelly, as an independent candidate for governor, allowing the Republicans to carry the state with a plurality of the vote.

[27] As the New York delegation left for the national convention in Cincinnati, Tilden gave a letter to one of his chief supporters, Daniel Manning, suggesting that his health might force him to decline the nomination.

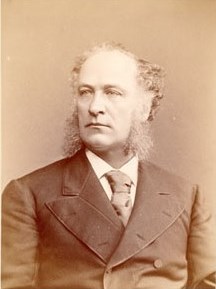

As one of a relative handful of conservative Democrats in the Senate at the time, Bayard began his career opposing vigorously, if ineffectively, the Republican majority's plans for the Reconstruction of the Southern states after the Civil War.

[33] The gold standard was less popular in the South, but there Bayard stacked his years-long advocacy in the Senate for pro-Southern conservative policies against Tilden's political machine and wealth in the contest for Southern delegates.

[35] At the same time, Bayard's uncompromising stance on the money question pushed some Democrats to support Major General Winfield Scott Hancock, who had not been identified with either extreme in the gold–silver debate and had a military record that appealed to Northerners.

[37] Winfield Scott Hancock represented an unusual confluence in the post-war nation: a man who believed in the Democratic Party's principles of states' rights and limited government, but whose anti-secessionist sentiment was unimpeachable.

[38] A native of Pennsylvania, Hancock graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1844 and began a forty-year career as a soldier.

[41] In the Peninsula Campaign of 1862, he led a critical counterattack and earned the nickname "Hancock the Superb" from his commander, Major General George B.

[45] As military governor of Louisiana and Texas in 1867, Hancock had won the respect of the white conservative population by issuing his General Order Number 40, in which he stated that if the residents of the district conducted themselves peacefully and the civilian officials performed their duties, then "the military power should cease to lead, and the civil administration resume its natural and rightful dominion.

Some were unsure whether, after eight years of Grant, himself a former general, the party would be wise to give the nomination to another "man on horseback", but Hancock remained among the leading contenders as the convention began that June.

[51][52] In April 1880, the New York Star published a tale that Tilden had bowed out of the race and instructed the Irving Hall faction to back Payne for the presidency.

With his sympathies as broad as this great continent, a private character as spotless as the snow from heaven, a judgment as clear as the sunlight, an intellect as keen and bright as a flashing sabre, honest in thought and deed, the people all know him by heart.

"Great in genius, correct in judgment," as McSweeney described him in a lengthy speech, Thurman was "of unrivaled eloquence in defense of the right, with a spotless name, he stands forth as a born leader of the people.

Hubbard praised Hancock's conduct as military governor of Texas and Louisiana, saying, "in our hour of sorrow, when he held his power at the hands of the great dominant Republican party ... there stood a man with the constitution before him, reading it as the fathers read it; that the war having ended we resumed the habiliments that as a right belong to us, not as a conquered province, but as a free people.

After that, according to the party records, "every delegate was on his feet and the roar of ten thousand voices completely drowned the full military band in the gallery.

Only Indiana refrained completely from joining in, casting its 30 votes for Hendricks; two Bayard voters from Maryland and one Tilden man from Iowa were the remaining hold-outs.

The platform was, in the words of historian Herbert J. Clancy, "deliberately vague and general" on some points, designed to appeal to the largest number possible.

[98] In it, they pledged to work for "constitutional doctrines and traditions," to oppose centralization, to favor "honest money consisting of gold and silver", a "tariff for revenue only", and to put an end to Chinese immigration.

Democratic newspapers attacked the Republican nominee, James A. Garfield of Ohio, over rumors of corruption and self-dealing in the Crédit Mobilier affair, among others.

[9] Both parties knew that, with the end of Reconstruction and the disenfranchisement of black Southerners, the South would be solid for Hancock, netting 137 electoral votes of the 185 needed for victory.

[108] With fifteen years having passed since the end of the war, and Union generals at the head of both tickets, the bloody shirt was of less effect than it had been in the past.