William Hayden English

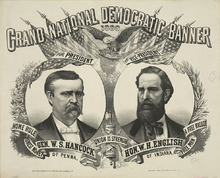

English and his presidential running mate, Winfield Scott Hancock, lost narrowly to their Republican opponents, James A. Garfield and Chester A. Arthur.

Elisha English quickly became involved in local politics as a Democrat, serving in the state legislature as well as building a prominent business career.

[5] English attended the 1848 Democratic National Convention in Baltimore, where he supported Lewis Cass, the eventual presidential nominee.

[3] Democrats were in the majority at the convention, and their proposals were incorporated into the new law, including increasing the number of elective offices, guaranteeing a homestead exemption, and restricting voting rights to white men.

[b][8] Holding the office of Speaker increased English's influence throughout the state; in 1852, the Democrats chose him as their nominee for the federal House of Representatives from the newly reconfigured 2nd district.

That if the people of Kentucky believe the institution of slavery would be conducive to their happiness, they have the same right to establish and maintain that we of Indiana have to reject it; and this doctrine is just as applicable to States hereafter to be admitted as to those already in the Union.

At that time, the simmering disagreement between the free and slave states heated up with the introduction of the Kansas–Nebraska Act, proposed by Illinois Democrat Stephen A. Douglas, which would open the Kansas and Nebraska territories to slavery, an implicit repeal of the Missouri Compromise of 1820.

[18] In December 1857, in an election boycotted by free-state partisans, Kansas adopted the pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution and petitioned Congress to be admitted as a slave state.

The Bill also required Kansans to renounce the unusually large grant of federal lands they had requested in the Lecompton Constitution.

[21] English declined to run for reelection in 1860 but he gave several speeches advocating compromise and moderation in the growing North-South divide.

[22] After southern secession occurred and the Civil War began, Governor Oliver P. Morton offered English command of a regiment, but he declined it since he had no military knowledge or interests.

English lent money to the state government to cover the expenses of outfitting the troops and served as provost marshal for the 2nd congressional district.

[23] After retiring from Congress, English spent a year at his home in Scott County before he relocated to Indianapolis, the state capital.

He turned over management of the Opera House to his son, William Eastin English, who was interested in the theater and had just married an actress, Annie Fox.

[29] After leaving the House of Representatives, English remained in touch with local politics, and served as chairman of the Indiana Democratic Party.

[30] English attended the 1880 Democratic National Convention in Cincinnati as a member of the Indiana delegation, where he favored presidential candidate Thomas F. Bayard of Delaware, whom he admired for his support of the gold standard.

[34] He was not expected to add much to the ticket outside of Indiana, but the party leaders thought his popularity in that swing state would help Hancock against James A. Garfield and Chester A. Arthur, the Republican nominees.

In that letter, English called the disputes of the Civil War settled, and promised a "sound currency, of honest money", the restriction of Chinese immigration, and a "rigid economy in public expenditure".

[41] Garfield's campaign used this statement to paint the Democrats as unsympathetic to the plight of industrial laborers, who benefited from the high protective tariff then in place.

[42] In the end, English was proven wrong: the Democrats and Hancock failed to carry any of the Midwestern states they had targeted, including Indiana.

He also became more interested in local history, joining a reunion of the survivors of the 1850 state constitutional convention, which met at his opera house in 1885.

[27] He became the president of the Indiana Historical Society and wrote two volumes, which were published at his death: Conquest of the Country Northwest of the River Ohio, 1778–1783; and Life of General George Rogers Clark.

His grandson, William English Walling, the son of his daughter Rosalind, was a co-founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

[46] An extensive collection of English's personal and family papers is housed at the Indiana Historical Society in Indianapolis, where it is open for research.