1880 United States presidential election

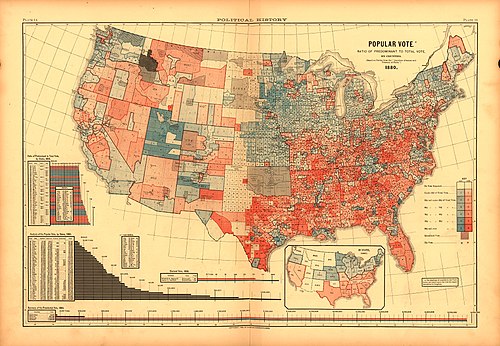

In a campaign fought mainly over issues of Civil War loyalties, tariffs, and Chinese immigration, Garfield narrowly won both the electoral and popular vote.

Of the men vying for the Republican nomination, the three strongest candidates leading up to the convention were former president Ulysses S. Grant, Senator James G. Blaine and Treasury Secretary John Sherman.

After the thirty-fifth ballot, Blaine and Sherman delegates switched their support to the new "dark horse" candidate, Representative James A. Garfield from Ohio.

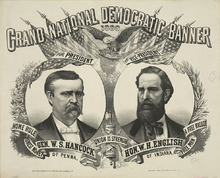

[23] As the convention opened, some delegates favored Bayard, a conservative senator, while others supported Hancock, a career soldier and Civil War hero.

Still others flocked to men they saw as surrogates for Tilden, including Henry B. Payne from Ohio, an attorney and former congressman, and Samuel J. Randall from Pennsylvania, the Speaker of the United States House of Representatives.

[30] The reduction of the money supply, combined with the economic depression, made life harder for debtors, farmers, and industrial laborers; the Greenback Party hoped to draw support from these groups.

[28] Beyond their support for a larger money supply, they also favored an eight-hour work day, safety regulations in factories, and an end to child labor.

James B. Weaver, an Iowa congressman and Civil War general, was the clear favorite, but two other congressmen, Benjamin F. Butler from Massachusetts and Hendrick B. Wright from Pennsylvania, also commanded considerable followings.

[32] More tumultuous was the fight over the platform, as delegates from disparate factions of the left-wing movement clashed over women's suffrage, Chinese immigration, and the extent to which the government should regulate working conditions.

[40] Garfield opposed Confederate secession, served as a major general in the Union Army during the Civil War, and fought in the battles of Middle Creek, Shiloh, and Chickamauga.

[43] Garfield initially agreed with Radical Republican views regarding Reconstruction, but later favored a moderate approach for civil rights enforcement for freedmen.

[46] He straddled the divide on civil service reform, saying that he agreed with the concept, while promising to make no appointments without consulting party leaders, a position 20th-century biographer Allan Peskin called "inconsistent".

Known to his Army colleagues as "Hancock the Superb", he was noted in particular for his personal leadership at the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863, where he led the defense of Pickett's Charge, getting wounded in the process.

During Reconstruction, he sided with then-President Andrew Johnson in working for a quick end to military occupation of the South and a return to government by the pre-war establishment.

[50] Hancock's reputation as a war hero at Gettysburg, combined with his status as a prominent Democrat with impeccable Unionist credentials and pro-states' rights views, made him a quadrennial presidential possibility.

[60] Weaver's path to victory, already unlikely, was made more difficult by his refusal to run a fusion ticket in states where Democratic and Greenbacker strength might have combined to outvote the Republicans.

[62] Hancock and the Democrats expected to carry the Solid South, while much of the North was considered safe territory for Garfield and the Republicans; most of the campaign would involve a handful of close states, including New York and Indiana.

Practical differences between the major party candidates were few, and Republicans began the campaign with the familiar theme of "waving the bloody shirt", reminding Northern voters that the Democratic Party was responsible for secession and four years of civil war, and that if they held power they would reverse the gains of that war, dishonor Union veterans, and pay Confederate soldiers' pensions out of the federal treasury.

[63] With fifteen years having passed since the end of the war, and Union generals at the head of all of the major and minor party tickets, the appeal to wartime loyalties was of diminishing value in exciting the voters.

[62] The party's courtship of black voters, too, threatened the white Democratic establishment, leading to violent outbursts at Weaver's rallies and threats against his supporters.

[62] As Weaver campaigned in the North in September and October, Republicans accused him of purposely dividing the vote to help Democrats win a plurality in marginal states.

[61] In the September gubernatorial race in Maine, one such fusion ticket nominated Harris M. Plaisted, who narrowly defeated the incumbent Republican in what was thought to be a safe state for that party.

[11] Garfield's campaigners used this statement to paint the Democrats as unsympathetic to the plight of industrial laborers, a group that benefited from a high protective tariff.

[65] The change in tactics appeared to be effective, as October state elections in Ohio and Indiana resulted in Republican victories there, discouraging Democrats about their chances the following month.

Both major parties (as well as the Greenbackers) pledged in their platforms to limit immigration from China, which native-born workers in the Western states believed was depressing their wages.

On October 20, however, a Democratic newspaper published a letter, purportedly from Garfield to a group of businessmen, pledging to keep immigration at the current levels so that industry could keep workers' wages low.

[73] Once the letter was exposed as a forgery, Garfield biographer Peskin believes it may even have gained votes for the Republican in the East, but it likely weakened him in the West.

[96] Before that result was known, however, Charles Guiteau, a mentally unstable man angry about not receiving a patronage appointment, shot Garfield in Washington, D.C., on July 2, 1881.

[98] Garfield's murder by a spoilsman inspired the nation to reform the civil service—and Arthur, erstwhile member of the Conkling machine, joined the cause.

[101] Tariffs, a major issue in the campaign, remained largely unchanged in the four years that followed, although Congress did pass a minor revision that reduced them by an average of less than 2 percent.