18th century glassmaking in the United States

In the southeastern portion of the Province of Pennsylvania, Henry Stiegel was the first American producer of high–quality glassware known as crystal.

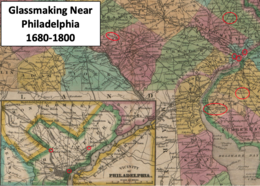

In the United States, the first use of coal as a fuel for glassmaking furnaces is believed to have started in 1794 at a short-lived factory on the Schuylkill River near Philadelphia.

Many of the skilled glass workers in the United States during the 17th and 18th centuries came from the German-speaking region of Europe.

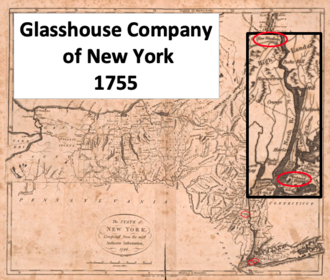

Glass works in New Amsterdam and New York City, the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, Philadelphia, and the province of New Jersey's Glassboro are often mentioned by historians.

Much of the evidence concerning the 17th century New Amsterdam glass factories has been lost, and a 17th-century Massachusetts glassworks did not last long.

However, it is thought that there were no more than a dozen glass works of significant size producing in the United States in 1800.

Glassmakers use the term "batch" for the sum of all the raw ingredients needed to make a particular glass product.

The cullet melts faster than the other ingredients, which results in some savings in fuel cost for the furnace.

[10] Annealing was originally conducted in the United States using a kiln that was sealed with the fresh glass inside, heated, and gradually cooled.

[11] During the 1860s annealing kilns were replaced in the United States with a conveyor oven, called a lehr, that was less labor-intensive.

[18] Alternative fuels such as natural gas and oil did not become available in the United States until the second half of the 19th century.

[20] Glassmaking methods and recipes were kept secret, and most European countries forbade immigration to the United States by glassworkers.

[21] The first attempt to produce glass in what became the United States happened in 1608 in the English (later British) Colony of Virginia near the settlement at Jamestown.

[23] Glassmaking was conducted for a short time in the Colony of Massachusetts Bay near Salem in the 1640s, and in the province of Pennsylvania near Philadelphia in the 1680s.

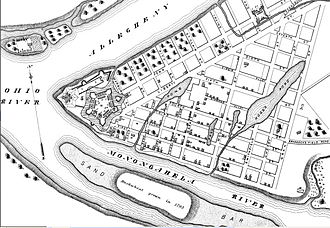

[26] Waterways provided transportation networks for the glass factories before the construction of highways and railroads.

[29] Prior to 1800, about two dozen glass works operated in the English colonies that became the United States, and some of them continued production into the 19th century.

[30] In 1738 Caspar Wistar, a German immigrant and manufacturer of brass buttons in Philadelphia, began plans for a glass works by purchasing land in Salem County, New Jersey.

[32] Wistar, who was originally from the Palatine region of what is now Germany, hired German glassworkers to make bottles, tableware, and window glass.

[43] He became a citizen of the English colony of Pennsylvania in 1760, and changed his name to Henry William Stiegel.

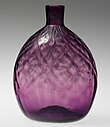

[50] The lead glass of this time period, commonly known as crystal because it was colorless and transparent, was typically used for fine tableware.

[57] The brothers were led by Solomon (the original land holder) and Daniel Stanger, and their glass works was the second (after Wistar) located in "South Jersey".

He purchased land in Frederick County, Maryland along Bennett's Creek to the north and east of Sugarloaf Mountain.

[71] Archaeological evidence suggests his bottles were made with a transparent green glass that did not require molds.

[72] Amelung had invested more money in glassmaking than anyone ever had (at the time), and his factory produced impressive quality glass—but his business failed after 11 years.

[75][Note 6] The domestic glass works were typically located near waterways that provided a transportation resource.

[136] The United States Embargo Act of 1807, and the War of 1812, made red lead extremely difficult for American companies to acquire.

[140] Glassmaking on the East Coast of the United States peaked before 1850, as plants shifted to Pittsburgh because of the availability of coal for fuel.

[141] By 1850, the United States had 3,237 free men above age 15 who listed their occupation as part of the glass manufacturing process.