1940–1946 in French Indochina

During World War II Japan would station a large number of soldiers and sailors in Vietnam although the French administrative structure was allowed to continue to function.

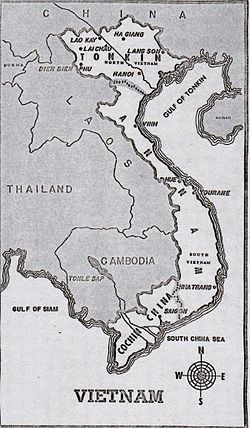

[3] The rising power of Japan in Vietnam encouraged nationalist groups to revolt from French rule in Bac Son near the Chinese border and in Cochinchina.

"[9] The United States declared war on Japan after the Japanese launched invasions throughout Southeast Asia and bombed Pearl Harbor in Hawaii.

[11] The French Sûreté discovered a Việt Minh base in Cao Bằng Province with arms and other material and warned of an immediate need "to re-establish authority."

The Việt Minh at this time controlled much of the border areas on northern Vietnam in Cao Bằng, Bắc Kạn, and Lạng Sơn provinces.

Hurley "had increasing evidence that the British, French, and Dutch are working...for the attainment of imperialistic policies and he felt we should do nothing to assist them in their endeavors which run counter to U.S.

"[17] U.S. General Claire Lee Chennault in Chongqing said that "any help or aid given by us [to Vietnam] shall be in such a way that it cannot possibly be construed as furthering the political aims of the French.

Japan persuaded the former emperor Bảo Đại to declare Vietnam independent of France and set up a puppet government headed by Trần Trọng Kim.

[20] Ho Chi Minh and Phạm Văn Đồng met with American Captain Charles Fenn who worked for the Office of Strategic Services in Kunming, China.

[25] The United States Department of War authorized General Wedemeyer in China to support French forces in Vietnam "providing they represent only a negligible diversion" from U.S. priorities.

Southeast Asian specialists at the State Department complained later that the policy paper deliberately excluded information about President Roosevelt's opposition to the French in Indochina.

[30] During this month, the Japanese also launched a series of raids against the Viet Minh, with the 21st Division striking bases in Tonkin while the military police arrested 300 suspects.

[31] Three U.S. soldiers from the OSS led by Major Allison Thomas parachuted into the Việt Minh's base camp in northern Viet Nam.

[33] 19 July A major Viet Minh strike occurred at Tam Dao internment camp, in which 500 soldiers killed fifty Japanese guards and officials, freeing French civilians who were escorted to the Chinese border.

[44] British forces of the Indian Army numbering 20,000, led by General Douglas Gracey, entered Saigon to accept the surrender of Japanese troops south of the 16th parallel of Vietnam.

"[46] General Philip E. Gallagher, commander of the U.S. military mission in Hanoi, reported that Ho Chi Minh was a "product of Moscow" but that "his party represented the real aspirations of the Vietnamese people for independence.

[47] General Gracey, commander of British forces in Saigon, declared martial law and released and armed more than 1,000 French soldiers held prisoner by the Japanese.

[53] In a meeting with U.S. Army officers General Gallagher and Major Patti, Ho Chi Minh "expressed the fear that the Allies considered Indochina a conquered country and that the Chinese came as conquerors."

[53] U.S. General Gallagher in Hanoi reported a "noticeable change in the attitude of the Annamites [Vietnamese] here...since that became aware of the fact that we were not going to interfere and would probably help the French.

"[57] Former Catholic monk and supporter of French leader Charles de Gaulle, Thierry d'Argenlieu arrived in Saigon as High Commissioner for Indochina.

Described by one wag as having "the most brilliant mind of the twelfth century", D'Argenliu shared De Gaulle's belief that the French empire, including Indochina, should be retained intact.

[58] At a meeting in Hanoi the Indochina Communist Party dissolved itself, citing a need to foster national unity in search of independence from France as the reason.

[64] French General Leclerc declared that, as a result of his military campaigns against nationalist groups, "the pacification of Cochinchina [southern Vietnam] is entirely achieved.

Leclerc said "it would be very dangerous for the French representatives at the negotiations to let themselves be fooled by the deceptive language (democracy, resistance, the new France) that Ho Chi Minh and his team utilize to perfection.

The fact that the ceasefire proved to be effective was a measure of the control the Việt Minh had over nationalist groups in southern Vietnam even though its power base was in the north.

With the departure of the Chinese army in June, Giap had crushed the pro-Chinese nationalist groups in northern Vietnam, killing hundreds or thousands of their followers and, despite a cease fire, engaged the French when they attempted to expand their control out of the cities to the countryside.

The Việt Minh, said historian Frederik Logevall, "previously had genuine legitimacy in calling themselves a broad-based nationalist front" but were now "synonymous with the Communist movement.

[86] The U.S. Department of State in Washington informed its personnel worldwide that the Việt Minh were communists and that the French presence in Vietnam was imperative "as an antidote to Soviet influence [and] future Chinese imperialism.

The Việt Minh military leader, Võ Nguyên Giáp, had three divisions of soldiers stationed near Hanoi and used his few pieces of artillery to blast away at the French.

The communists were attempting to maintain a place in the Cabinet of Ministers and in mainstream politics of France and had little interest in supporting the Việt Minh in Vietnam.