1947–1950 in French Indochina

French Overseas Minister Marius Moutet visiting Vietnam said that the Việt Minh "have fallen to the lowest level or barbarity" and that "before there is any negotiation it will be necessary to get a military decision.

"[3] France expanded the powers of the Vietnamese-led government of Cochinchina to include self-government on internal affairs and an election for a legislature.

[5] French forces had pushed the Việt Minh out of most major towns and cities in northern and central Vietnam, including Hanoi and Huế.

Ho Chi Minh maintained his self-proclaimed independent government of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in Thái Nguyên, north of Hanoi.

Việt Minh diplomat Pham Ngoc Thach in Bangkok wrote letters to American companies offering economic concessions if they would invest in Vietnam.

[13] Secretary of State George Marshall asked diplomats in Southeast Asia and Europe their opinion of the Việt Minh and its government, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam.

However, from France American diplomats said that Ho Chi Minh "maintains close connections in Communist circles" and that his government, if it became independent, "would immediately be run in accordance with dictates from Moscow.

[16] American consuls in Hanoi and Saigon reported to Washington that the French were planning a major military operation against the Việt Minh.

[17] French General Jean Étienne Valluy led Operation Léa in an attempt to destroy the Việt Minh and capture or kill its leaders.

Ho Chi Minh and military leader Võ Nguyên Giáp barely escaped but the French attack bogged down and Operation Léa was a failure.

[20] American Consul Edwin C. Rendell in Hanoi reported to Washington that the "hard core' of Việt Minh resistance had not been broken by French military offensives.

[22] Bảo Đại finally returned to Vietnam to attend the signing of a new agreement between France and General Nguyễn Văn Xuân, head of the French-sponsored government of Cochinchina.

The U.S. Consul in Saigon, George M. Abbott, said that a French truce with the Việt Minh "would result in the non-communist elements [in Vietnam] being swallowed up.

"[24] George Abbott, the U.S. Consul in Saigon, said prompt action was needed by France to grant real independence to a Bảo Đại government.

[25] The U.S. Department of State said that the policy of maintaining French support for a Western European coalition to contain the Soviet Union took precedence over attempting to persuade France to concede more independence to Vietnamese and end the war.

[26] The State Department also concluded that "we are all too well aware of the unpleasant fact that Communist Ho Chi Minh is the strongest and perhaps the ablest figure in Indochina and that any suggested solution which excludes him is an expedient of uncertain outcome.

We are naturally hesitant to press the French too strongly or to become deeply involved so long as we are not in a position to suggest a solution or until we are prepared to accept the onus of intervention.

Under Secretary of State Robert A. Lovett said the U.S. should not give its full support to the Bảo Đại government which existed only because of French military forces in Vietnam.

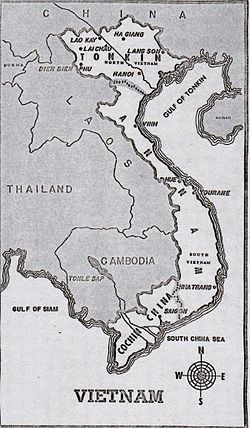

The Accord reaffirmed Vietnamese autonomy and provided for the union of the three French protectorates of Tonkin, Annam, and Cochinchina, but France retained control of the military and foreign affairs.

Secretary of State Dean Acheson said that U.S. military aid might be "the missing component" in defeating communist insurgency in Vietnam.

[35] Reflecting the strong anti-communist views in the U.S., The New York Times said that "the disciplined machinery of international communism, directed by Moscow, is carrying out perhaps the most brilliant example of global political warfare so far known by draining the potential strength of France in the Indo-China civil war."

Ambassador Loy Henderson said that "the Bảo Đại government...reflects more accurately than rival claimants the nationalist aspirations of the people" of Vietnam.

"[45] U.S. President Harry Truman received and would later approve NSC 68, a secret policy paper prepared by U.S. foreign affairs and defense agencies.

This view was bolstered by the recent victory of communist forces in China and by domestic fears of communism, especially those aroused by Senator Joseph McCarthy and Congressman Richard Nixon.

"[46][47] The U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff wrote Secretary of Defense Johnson that French Indochina Vietnam was "a vital segment in the line of containment of communism stretching from Japan southward and around to the Indian peninsula."

[48] The liberal American magazine The New Republic said "Southeast Asia is the center of the cold war....America is late with a program to save Indo-China.

[52] The Korean War began, reinforcing the U.S. view that a monolithic communism directed by the Soviet Union was on the offensive in Asia and threatening to overthrow governments friendly to the United States and its allies.

[56] General Giap, commander of Việt Minh military forces, attacked a French post at Đông Khê in northern Vietnam with 5 regiments.

[59] U.S. Army Brigadier General Francis G. Brink assumed command of the U.S. military advisory group (MAAG) in Saigon.

[64] France concluded an agreement with the Bảo Đại government in Da Lat to create an independent Vietnamese army.