1946 California's 12th congressional district election

First elected to Congress in 1936, Voorhis had defeated lackluster Republican opposition four times in the then-rural Los Angeles County district to win re-election.

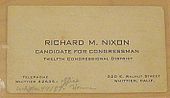

After failing to secure the candidacy of General George Patton, in November 1945 they settled on Lieutenant Commander Richard Nixon, who had lived in the district prior to his World War II service.

Nixon's campaign worked hard to generate publicity in the district, while Voorhis, dealing with congressional business in the capital, received little newspaper coverage.

At five debates held across the district in September and October, Nixon was able to paint the incumbent as ineffectual and to suggest that Voorhis was connected to communist-linked organizations.

The 12th stretched from just south of Pasadena to the Orange and San Bernardino county lines, encompassing such small towns as Whittier, Pomona and Covina.

[1] Voorhis, who gained a reputation as a respected and hard-working representative,[3] nicknamed "Kid Atlas" by the press for taking the weight of the world on his shoulders, was loyal to the New Deal.

[7] In 1940, he faced Captain Irwin Minger, a little-known commandant of a military school,[8] and his 1942 opponent, radio preacher and former Prohibition Party gubernatorial candidate Robert P. Shuler, "embarrassed GOP regulars".

[23] Beginning in February, the Republican hopeful began a heavy speaking schedule, addressing civic groups across the 400 square miles (1,000 km2) district.

[24] Congressman Voorhis's office sent the Nixons a government pamphlet entitled Infant Care, of which representatives received 150 per month to distribute to their constituents.

When Richard Nixon sent his rival a note of thanks in early April, the congressman responded with a letter proposing that the two debate once Congress adjourned in August.

[27] Hoeppel offered to enter the Democratic primary in exchange for a payment of several hundred dollars plus the promise of a civil service job once the Republican was elected.

Voorhis was privy to these events through an informant close to the former representative, and was convinced that Roy Day had arranged to pay Hoeppel's filing fee.

[32] Chotiner arranged for stories in local papers alleging that Voorhis had been endorsed by "the PAC", hoping that voters would take that to mean the Congress of Industrial Organizations's Political Action Committee (CIO-PAC).

Nixon, who had notified organizers that he would be late due to another commitment, arrived during Voorhis's speech, and remained backstage until the congressman had completed his talk.

[45] In response, Nixon reached into his pocket and pulled out a copy of a Southern California NCPAC bulletin mentioning the group's endorsement of Voorhis.

"[45] On September 19, Voorhis wired the NCPAC's Los Angeles and New York offices, requesting that "whatever qualified endorsement the Citizens PAC may have given me be withdrawn".

[54] The Republican candidate stated that he was fighting for "the person on a pension trying to keep up with the rising cost of living ... the white-collar worker who has not had a raise ... Americans have had enough, and they have come to the conclusion that they are going to do something.

[58] Time magazine's post-election issue came out in mid-November, and it praised the future president for "politely avoid[ing] personal attacks on his opponent".

[19] The day after the election, Voorhis issued a concession statement, wishing Nixon well in his new position, and stating: I have given the best years of my life to serving this district in Congress.

[61] Former congressman Hoeppel, who gathered just over one percent of the vote, wrote Nixon after the election, stating that he had never expected to win, and that his purpose had been "to expose what I considered to be the alien-minded, un-American, PAC, Red, congressional record of the Democratic incumbent".

"[70] Jonathan Aitken, also a biographer of Nixon, attributes the later scrutiny to "the unexpected toppling of a liberal icon and [the Democratic Party's] regret over the meteoric rise of the new Republican hero who won the seat".

[73] In an early draft of his memoir, Voorhis wrote that he had documentation showing that "the Nixon campaign was a creature of big eastern financial interests".

"[78] According to Morris, the Committee of One Hundred represented wealthy interests, and Nixon benefited from "the University Club ... the corporate levies, the vastly larger forces arrayed against Voorhis".

[79] Nixon himself addressed this point in his memoir: As I moved up the political ladder, my adversaries tried to picture me as the hand-picked stooge of oil magnates, rich bankers, real estate tycoons and conservative millionaires.

"[88] Bullock indicated that regardless of the tactics used, Nixon would likely have beaten the incumbent given the national Republican tide that swept the party into power in the House of Representatives for the first time since 1931.

The campaign targeted smaller papers, especially the small weekly newspapers that were distributed for free; Republican surveys found that these were widely read and trusted.

[91] Voorhis's campaign, described by Bullock as "traditionally amateurish and poorly put together",[92] was slow to perceive the threat presented by Nixon[93] and remained continually on the defensive.

"[64] In the same article, the Los Angeles Times described Voorhis's campaign as "undermanned, underfinanced, outgunned, outmaneuvered and he apparently was on the wrong side of most of the issues of the day".

[77] Nixon later stated, "In 1946, a damn fool incumbent named Jerry Voorhis debated a young unknown lawyer, and it cost him the election.

"[d] Gellman itemized Voorhis's other errors: "He never established a viable Democratic organization; instead he relied on his father and friends to evaluate voters' likely habits.