2001 anthrax attacks

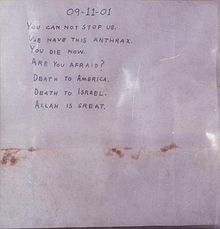

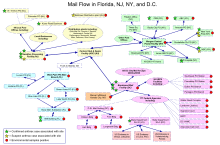

Letters containing anthrax spores were mailed to several news media offices and to senators Tom Daschle and Patrick Leahy, killing five people and infecting 17 others.

[14] The first known victim of the attacks, Robert Stevens, who worked at the Sun tabloid, also published by AMI, died on October 5, 2001, four days after entering a Florida hospital with an undiagnosed illness that caused him to vomit and be short of breath.

Scientists examining the anthrax from the New York Post letter said it was a clumped coarse brown granular material which looked similar to dog food.

The Leahy letter had been misdirected to the State Department mail annex in Sterling, Virginia, because a ZIP Code was misread; a postal worker there, David Hose, contracted inhalational anthrax.

[50] On October 24, 2001, USAMRIID scientist Peter Jahrling was summoned to the White House after he reported signs that silicon had been added to the anthrax recovered from the letter addressed to Daschle.

Seven years later, Jahrling told the Los Angeles Times on September 17, 2008, "I believe I made an honest mistake,” adding that he had been "overly impressed" by what he thought he saw under the microscope.

Two bioweapons experts that were utilized as consultants by the FBI, Kenneth Alibek and Matthew Meselson, were shown electron micrographs of the anthrax from the Daschle letter.

Another group said it "was a diabolical advance in biological weapons technology.”[62] The article describes "a technique used to anchor silica nanoparticles to the surface of spores" using "polymerized glass.”[62] An August 2006 article in Applied and Environmental Microbiology, written by Douglas Beecher of the FBI labs in Quantico, Virginia, states "Individuals familiar with the compositions of the powders in the letters have indicated that they were comprised simply of spores purified to different extents.

The persistent credence given to this impression fosters erroneous preconceptions, which may misguide research and preparedness efforts and generally detract from the magnitude of hazards posed by simple spore preparations.

[64][65] In late October 2001, ABC chief investigative correspondent Brian Ross linked the anthrax sample to Saddam Hussein because of its purportedly containing the unusual additive bentonite.

[67] On October 29, 2001, White House spokesman Scott Stanzel "disputed reports that the anthrax sent to the Senate contained bentonite, an additive that ha[d] been used in Iraqi President Saddam Hussein's biological weapons program.” Stanzel said, "Based on the test results we have, no bentonite has been found.”[68] The same day, Major General John Parker at a White House briefing stated, "We do know that we found silica in the samples.

"[69] Just over a week later, Homeland Security Advisor Tom Ridge in a White House press conference on November 7, 2001, stated, "The ingredient that we talked about before was silicon.

[90] In December 2001, she published "A Compilation of Evidence and Comments on the Source of the Mailed Anthrax" via the web site of the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) claiming that the attacks were "perpetrated with the unwitting assistance of a sophisticated government program".

[102] Hatfill also sued The New York Times and its columnist Nicholas D. Kristof, as well as Donald Foster, Vanity Fair, Reader's Digest, and Vassar College for defamation.

[106] Rush D. Holt Jr. represented the district where the anthrax letters were mailed, and he said that circumstantial evidence was not enough and asked FBI director Robert S. Mueller to appear before Congress to provide an account of the investigation.

[111] Ivins told a mental health counselor more than a year before the anthrax attacks that he was interested in a young woman who lived out of town and that he had "mixed poison" which he took with him when he went to watch her play in a soccer match.

The counselor was so alarmed by his emotionless description of a specific, homicidal plan that she immediately alerted the head of her clinic and a psychiatrist who had treated Ivins, as well as the Frederick Police Department.

Ivins threatened other scientists, made equivocal statements about his possible involvement in a conversation with an acquaintance, and put together outlandish theories in an effort to shift the blame for the anthrax mailings to people close to him.

[118] A DOJ summary report of February 19, 2010, said that "the evidence suggested that Dr. Ivins obstructed the investigation either by providing a submission which was not in compliance with the subpoena, or worse, that he deliberately submitted a false sample.

Below is the media text with the highlighted As and Ts: According to the FBI, Summary Report issued on February 19, 2010, following the search of Ivins' home, cars, and office on November 1, 2007, investigators began examining his trash.

[11]: 59 The FBI Summary Report proceeds to say: "From this analysis, two possible hidden meanings emerged: (1) 'FNY' – a verbal assault on New York, and (2) PAT – the nickname of [Dr. Ivins'] Former Colleague #2."

[133] Reasons cited for these doubts include that Ivins was only one of 100 people who could have worked with the vial used in the attacks and that the FBI could not place him near the New Jersey mailbox from which the anthrax was mailed.

[133][134] The FBI's own genetic consultant, Claire Fraser-Ligget, stated that the failure to find any anthrax spores in Ivins' house, vehicle or on any of his belongings seriously undermined the case.

[120] Noting unanswered questions about the FBI's scientific tests and lack of peer review, Jeffrey Adamovicz, one of Ivins' supervisors in USAMRIID's bacteriology division, stated, "I'd say the vast majority of people [at Fort Detrick] think he had nothing to do with it.

[138]In 2011 Leahy maintained to the Washington Post that the attacks had certainly involved other "people who at the very least were accessories after the fact," and also found it "strange that one person would target such an odd collection of media and political figures".

[151] In what appears to have been a response to lingering skepticism, on September 16, 2008, the FBI asked the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) to conduct an independent review of the scientific evidence that led the agency to implicate U.S. Army researcher Bruce Ivins in the anthrax letter attacks of 2001.

[9] However, despite taking this action, Director Mueller said that the scientific methods applied in the investigation had already been vetted by the research community through the involvement of several dozen nonagency scientists.

[160] The NAS committee released its report on February 15, 2011, concluding that it was "impossible to reach any definitive conclusion about the origins of the anthrax in the letters, based solely on the available scientific evidence".

Under heavy pressure from then Attorney General John D. Ashcroft, a bipartisan compromise in the House Judiciary Committee allowed legislation for the Patriot Act to move forward for full consideration later that month.

[181] A postal inspector, William Paliscak, became severely ill and disabled after removing an anthrax-contaminated air filter from the Brentwood mail facility on October 19, 2001.