2nd Iowa Infantry Regiment

After engaging the rebels, who were estimated as numbered between 80 and 100 men, Company A managed to save the bridge, capture five horses, and kill 18 Confederate soldiers.

Soon after, the regiment marched to Jackson and Pilot Knob, Missouri, and Fort Jefferson, Kentucky, for more guarding duty until reporting back to Bird's Point on September 24, 1861.

Because of this, General Henry Halleck ordered that the regiment, which was well-liked by the people of St. Louis and the prisoners, march through the streets on the way to the steamer T. H. McGill in disgrace without music or colors.

Strategically, the capture of Fort Donelson meant navigability for steamers along the Cumberland River, a direct path to the rear of Confederate forces in Kentucky and Tennessee, as well as a hold on valuable supply and communications lines.

The Federal army, under the leadership of General Ulysses S. Grant, managed to create an attacking force that numbered approximately 20,000 soldiers.

During the fighting the previous day, a brigade advanced on the extreme left, where the 2nd Iowa was eventually placed, and suffered severe losses before retreating back to the skirmish line.

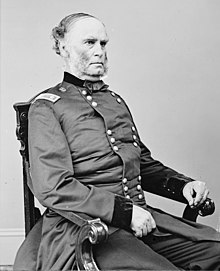

[16] After their arrival on February 14, 1862, the 2nd Iowa was placed at the extreme left of Grant's force as a part of General Charles Smith's division, and Colonel Tuttle sent companies A and B ahead as skirmishers.

The regiment marched in line over the open meadow, through a gully, over a rail fence, and up a hill cluttered with broken trees when suddenly the enemy came into sight and a steady rain of lead poured into the ranks of the brave men.

Don’t stop for me!” At least five members of the color guard were wounded or killed before Corporal Voltaire Twombly would take the flag and be hit in the chest by a spent ball.

General Halleck, who just ten days ago ordered the regiment to march in shame, spoke of the bravery of the men of the 2nd Iowa.

They had the honor of leading the column which entered Fort Donelson.”[23] The price for glory came at a cost; the 2nd Iowa had 32 killed and 164 wounded during the battle.

The 2nd Iowa would remain at Fort Donelson until March 6, 1862, when the regiment would be called to Pittsburg Landing to fight in the Battle of Shiloh.

[25] The Confederate forces attacked Shiloh with a source of approximately 43,000 men under the command of Generals Albert Johnston and Gustave Beauregard.

There the 2nd Iowa experienced pleasant weather and light drill duty until Sunday, April 6, when General Grant ordered the brigade to the front.

The 2nd Iowa Infantry repelled several enemy attacks on that day, resulting in great losses for the Confederate army.

The fighting was so severe in this area that the place became known as “The Hornets’ Nest.” The brigade stood strong in this position for six hours until the Confederate army assembled artillery and blasted the location.

The 2nd Iowa made it to the safety of the Federal gunboats at Pittsburg Landing, while General Don Carlos Buell's army provided reinforcements and re-established a line of defense before nightfall.

The following morning the battle resumed, the 2nd Iowa being used as reserves until 1:00 p.m., when Brigadier General William Nelson ordered a charge against the Confederates who were holding a camp of an Ohio regiment.

James B. Weaver was third in command as major from Company G.[30] During the fighting at Shiloh, the 2nd Iowa again proved themselves as brave and vital to the Federal forces, and seven of the men sacrificed their lives and an additional thirty seven were wounded.

The 2nd Iowa participated in the unsuccessful chase after General Beauregard before reporting back to Camp Montgomery, located near Corinth, on June 15.

The situation would not change until early September when Confederate General Sterling Price advanced his troops to the city of Iuka, just twenty miles east from Corinth.

[34] During the early morning of October 3, the 2nd Iowa, being a part of the First Brigade of the Second Division of the Army of the Tennessee under Brigadier General Thomas A. Davies, moved their line of defense two miles ahead from where they were currently positioned (northwest of Corinth) in order to prepare for an engagement with the enemy.

Corporal John Bell of the 2nd Iowa described the final attack by the Confederates when he wrote: "No braver or more desperate assault was ever made, and as the shot and shells of our siege guns, accurately trained by months of skillful practice, tore dreadful gaps in the ranks of the enemy with the only effect of causing them to close up these gaps and press resistlessly forward, apparently as devoid of fear as wooden men, I thought, “These are not human beings; they are devils.”"[37] However brave the men of the Confederate army were on the charge, their effort was of no use.

For a short period of time in the summer, being placed on outpost duty became more dangerous than usual because enemy personnel were firing upon the soldiers with increased frequency.

After joining the Federal army and learning the locations of the outposts, he deserted and formed a Confederate guerilla unit, which would attack these sites.

In April 1864, the regiment left Pulaski to join the Atlanta campaign as a member of the 2nd Division of the Sixteenth Corps of the District of Tennessee.

The men marched close to the enemy at dusk on the 27th and established trenches and spent the night on the front, preparing for battle the next day.

The next day, the 2nd Iowa was placed in the rear of their division and did not fight again until General Johnston was forced from Dallas and made his new line of defense by Kennesaw Mountain.

On July 22, during a skirmish in which the 2nd Iowa captured twenty prisoners and an enemy's stand of colors, General McPherson was killed and Lieutenant Colonel Howard was injured, leaving the command of the regiment in the hands of Major Matthew G. Hamill.

The next day the units held the position gained, and by the second of September, the enemy had evacuated Atlanta and the surrounding area and the battle was over.