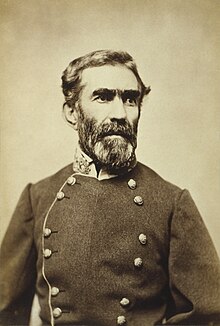

William Rosecrans

His brusque, outspoken manner and willingness to quarrel openly with superiors caused a professional rivalry with Grant (as well as with Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton) that would adversely affect Rosecrans' career.

Crandall was a veteran of the War of 1812, in which he served as adjutant to General William Henry Harrison, and then subsequently ran a tavern and store as well as a family farm.

[1] Rosecrans was descended from the Dutch-Scandinavian nobleman Harmon Henrik Rosenkrantz (1614–1674), who arrived in New Amsterdam in 1651,[2] but the family name changed spelling during the American Revolutionary War.

He graduated from West Point in 1842, fifth in his class of 56 cadets, which included notable future generals such as James Longstreet, Abner Doubleday, Daniel Harvey "D. H." Hill, and Earl Van Dorn.

According to University of Virginia historian William B. Kurtz, “unlike many men of his era content to leave religion to (that of) their wives, he played the central role in his family’s faith life.

Promoted to the rank of colonel, Rosecrans briefly commanded the 23rd Ohio Infantry Regiment, whose members included Rutherford B. Hayes and William McKinley, both future presidents.

He served briefly in Washington, where his opinions clashed with those of newly appointed Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton on tactics and Union command organization for the Shenandoah Valley campaign against Stonewall Jackson.

Considering this delay, Grant ordered Ord to move within 4 miles (6.4 km) of the town, but to await the sound of fighting between Rosecrans and Price before engaging the Confederates.

A fresh north wind, blowing from Ord's position in the direction of Iuka, caused an acoustic shadow that prevented the sound of the guns from reaching him, and he and Grant knew nothing of the engagement until after it was over.

Rosecrans's cavalry and some infantry pursued Price for 15 miles (24 km), but owing to the exhausted condition of his troops, his column was outrun and he gave up the pursuit.

He believed that the Confederate commander would not be foolhardy enough to attack the fortified town and might well instead choose to strike the Mobile and Ohio Railroad and maneuver the Federals out of their position.

Then came a quick rally which his magnificent bearing inspired, a storm of grape from the batteries tore its way through the Rebel ranks, reinforcements which Rosecrans sent flying gave impetus to the National advance, and the charging column was speedily swept back outside the entrenchments.

His biographer, Lamers, paints a romantic picture: One of Davies' men, David Henderson, watched Rosecrans as he dashed in front of the Union lines.

"[32]Peter Cozzens, author of a recent book-length study of Iuka and Corinth, came to the opposite conclusion: Rosecrans was in the thick of battle, but his presence was hardly inspiring.

Grant had given him specific orders to pursue Van Dorn without delay, but he did not begin his march until the morning of October 5, explaining that his troops needed rest and the thicketed country made progress difficult by day and impossible by night.

As a devout Catholic, he carried a crucifix on his watch chain and a rosary in his pocket, and he delighted in keeping his staff up half the night debating religious doctrine.

[38] As Rosecrans raced across the battlefield directing units, seeming ubiquitous to his men, his uniform was covered with blood from his friend and chief of staff, Col. Julius Garesché, beheaded by a cannonball while riding alongside.

He stemmed the tide of retreat, hurried brigades and divisions to the point of danger, massed artillery, infused into them his own dauntless spirit, and out of defeat itself, fashioned the weapons of victory.

As at Rich Mountain, Iuka and Corinth, it was his personal presence that magnetized his plans into success.The armies paused on January 1, but the following day, Bragg attacked again, this time against a strong position on Rosecrans's left flank.

"[41] Rosecrans's XIV Corps was soon redesignated the Army of the Cumberland, which he kept in place occupying Murfreesboro for almost six months, spending the time resupplying and training, for he was reluctant to advance on the muddy winter roads.

He received numerous entreaties from President Lincoln, Secretary of War Stanton, and General-in-Chief Halleck to resume campaigning against Bragg, but rebuffed them through the winter and spring.

A primary concern of the government was that if Rosecrans continued to sit idly, the Confederates might move units from Bragg's army in an attempt to relieve the pressure that Union Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant was applying to Vicksburg, Mississippi.

Rosecrans threw aside his previous caution under the assumption that Bragg would continue to retreat and began to pursue with his army over three routes that left his corps commanders dangerously far apart.

By coincidence, Lt. Gen. James Longstreet had planned to lead a massive assault in that very area and the Confederates exploited the gap to full effect, shattering Rosecrans's right flank.

[52] The Union army managed to escape complete disaster because of the stout defense organized by Thomas on Horseshoe Ridge, heroism that earned him the nickname "Rock of Chickamauga."

Only hours after the defeat at Chickamauga, Secretary Stanton ordered Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker to travel to Chattanooga with 15,000 men in two corps from the Army of the Potomac in Virginia.

During the 1864 Republican National Convention, his former chief of staff, James Garfield, head of the Ohio delegation, telegraphed Rosecrans to ask if he would consider running to be Abraham Lincoln's vice president.

[63] Rosecrans was reelected in 1882 and became the chairman of the House Military Affairs Committee, a position in which he publicly opposed a bill that would provide a pension to former President Grant and his wife.

[66] Rosecrans spoke at a grand reunion of Union and Confederate veterans held at the Chickamauga battlefield on September 19, 1889, delivering a moving address praising national reconciliation.

[citation needed] An equestrian statue of Rosecrans, resting on a 55,000 pound black granite boulder, is located on the square surrounding the Town Hall of Sunbury, Ohio.