2nd Portuguese India Armada (Cabral, 1500)

Determined not to repeat Gama's mistakes, this one was to be a large and well-armed fleet of 13 ships and 1500 men, laden with valuable gifts and diplomatic letters to win over the potentates of the east.

[note 6] The fleet carried some twenty Portuguese degredados, who were criminal convicts who could fulfill their sentences by being abandoned along the shores of various places and exploring inland on the crown's behalf.

There are three surviving eyewitness accounts of this expedition: (1) an extended letter written by Pêro Vaz de Caminha (possibly dictated by Aires Correia), written from Brazil on May 1, 1500, to King Manuel I; (2) the brief letter by Mestre João Faras to the king, also from Brazil; and (3) the account of an anonymous Portuguese pilot, first published in Italian in 1507 (commonly referred to as the Relação do Piloto Anônimo, sometimes believed to be the clerk João de Sá).

The priority of the mission was to secure a treaty with Zamorin's Calicut (Calecute, Kozhikode), the principal commercial entrepôt of the Kerala spice trade and dominant feudal city-state on the Malabar coast of India.

[13] Sofala had been secretly visited and described by the explorer Pêro da Covilhã during his overland expedition a decade earlier (c. 1487), and he identified it as the endpoint of the Monomatapa gold trade.

[14] Among the pieces of evidence is an indication of an island in the area in a 1448 map of Andrea Bianco, apparently alluded to in the letter of Master João Faras; there is also the suggestion by Duarte Pacheco Pereira in his Esmeraldo de Situ Orbis that he had been sent on an expedition to a western landmass in 1498.

It is unknown why he chose such an unusual direction, but the most probable hypothesis is that he was simply following the wide arc in the South Atlantic to catch a favorable wind to carry them to the Cape of Good Hope.

From Cape Verde, the ship would cut across the doldrums below the equator, catch the southwest-bound equatorial drift, and turn into the southbound Brazil Current that will carry them down to the horse latitudes (30°S), where the prevailing westerlies begin.

[note 11] Alternative hypotheses forwarded for Cabral striking southwest are that he was trying to reach the Azores to repair his storm-battered fleet, that he was searching for and rounding up missing tempest-tossed ships, or that it was an intentional attempt to discover if there was any land by the Tordesillas line.

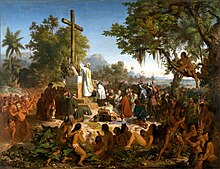

On April 26, the Octave of Easter Sunday, the Franciscan friar Henrique Soares of Coimbra went ashore to celebrate mass in front of 200 Tupiniquim Indians.

[note 12] On May 2, Cabral dispatched the supply ship back to Lisbon, with the Brazilian items and a letter to King Manuel I composed by the secretary Pêro Vaz de Caminha to announce the discovery.

After that, with a couple of Portuguese degredados left behind with the Tupiniquim of Porto Seguro,[27] Cabral ordered the eleven remaining ships to set sail and continue on their route to India.

Leaving behind two degredados, Luís de Moura and João Machado, and picking up two Gujarati pilots, Cabral's six-ship armada finally began its Indian Ocean crossing on August 7, 1500.

Hoping for a spectacle, the Zamorin himself came down to the beachfront to witness the engagement, but left in disgust when the Arab ship slipped past Ataide, who gave chase and eventually caught up to it near Cannanore.

[note 16] Cabral presented Correia's complaint to the Zamorin, and requested that he crack down on the Arab merchant guild or enforce Portuguese priority in the spice markets.

At the suggestion of Gaspar da Gama, the Goese Jew who had been accompanying the expedition, Cabral set sail south along the coast toward Cochin kingdom (Cochim, Kochi or Perumpadappu Swarupam), a small Hindu Nair city-state at the outlet of the Vembanad lagoon in the Kerala backwaters.

In early January 1501, while in Cochin, Cabral received missives from the rulers of Cannanore (Canonor, Kannur or Kolathunad), one of Calicut's reluctant rivals in the north, and Quilon (Coulão, Kollam or Venad Swarupam), which was further south and had once been a great Syrian Christian merchant city-state, being an entrepôt for cinnamon, ginger, and dyewood.

The encounter with a clearly recognizable Christian community in Kerala confirmed to Cabral what the Franciscan friars had already suspected back in Calicut, namely that Vasco da Gama's earlier hypothesis about a "Hindu Church" was mistaken.

Despite the Trimumpara Raja of Cochin's offer of military assistance against the Calicut fleet, Cabral decided to precipitously lift anchor and slip away rather than risk a confrontation.

Shortly after being separated from the main fleet at the Cape in June 1500, Dias had struck out too far east into the Indian Ocean and sighted the western coast of the island of Madagascar.

He was trapped by contrary winds, battered by tempests, attacked by Arab pirates, and forced aground on the Eritrean coast, unable to find food and water.

Cabral ordered the private ship Anunciada of Nuno Leitão da Cunha, the fastest in the fleet, to be placed under the command of veteran hand Nicolau Coelho.

In the meantime, Cabral landed the degredado António Fernandes on the African coast, with letters of instruction for Diogo Dias and any passing Portuguese expeditions, informing them of the dramatic turn of events in India, and warning them to avoid Calicut.

It is also possible that Fernandes had been instructed to make his way to Sofala overland, meet Tovar's ship there, and then proceed to explore inland from there to locate Monomatapa, though this does not explain why Cabral had given him the letters.

But Cabral and Miranda had decided to proceed on together towards Lisbon without him, so Ataíde made his way home alone, leaving behind a letter in a boot by a local watering hole giving an account of the expedition; Ataide's note would be found later that year by João da Nova's third armada.

[note 21] Setting out from Lisbon in May 1501, the expedition made a watering stop in early June at Bezeguiche, as the bay of Dakar, near present-day Senegal, was known to the Portuguese sailors of the time.

Just two days later, the lead ship of the returning India fleet—the Anunciada under Nicolau Coelho—sailed into Bezeguiche, which must have been a pre-arranged point of encounter for the Second Armada, surprised to find both Dias and the Brazilian mapping expedition there.

On June 23, the Anunciada, commanded by Nicolau Coelho, who had also been the first to deliver the news of Gama's expedition several years earlier, arrived in Lisbon and anchored in Belém.

The plenitude of brazilwood (pau-brasil) discovered by the mapping expeditions on its shores lured the interest of European cloth industry and led to the 1505 contract granted to Fernão de Loronha for the commercial exploitation of Brazil.

The lucrative brazilwood trade eventually drew competition from French and Spanish interlopers, forcing the Portuguese government to take a more active interest in Cabral's "Land of Vera Cruz".