Portuguese India Armadas

The rule that quickly emerged was that if an outbound armada doubled the Cape of Good Hope before mid-July, then it should follow the old "inner route" – that is, sail into the Mozambique Channel, up the East African coast until the equatorial latitude (around Malindi, in modern-day Kenya), then take the southwesterly monsoon across the ocean to India.

If, however, the armada doubled the Cape after mid-July, then it was obliged to sail the "outer route" – that is, strike out straight east from South Africa, go under the southern tip of Madagascar, and then turn up from there, taking a northerly path through the Mascarenes islands, across the open ocean to India.

The route from Mina down to South Africa involved tacking against the southeasterly trade winds and the contrary Benguela Current, a particularly tiresome task for heavy square rigged carracks.

The Cape was not only a confluence point of opposing winds, which created unpredictable whirlwinds, it also produced a strange and extraordinarily fast southerly current, violent enough to break a badly-sewn ship, and confusing enough to throw all reckoning out the window and lure pilots into grievous errors.

Although a Madagascar-hugging route cleared up the longitude problem, it was also abundant in fearful obstacles – coral islets, atolls, shoals, protruding rocks, submerged reefs, made for a particularly nerve-wracking experience to navigate, especially at night or in bad weather.

Mozambique's main attribute was its splendid harbor, which served as the usual first stop and collection point of Portuguese India armadas after the crossing of the Cape of Good Hope.

Although Mozambique islanders had established watering holes, gardens and coconut palm groves (essential for timber) just across on the mainland (at Cabaceira inlet), the Bantu inhabitants of the area were generally hostile to both the Swahili and the Portuguese, and often prevented the collection of supplies.

The Mozambican factor also collected East African trade goods that could be picked up by the armadas and sold profitably in Indian markets – notably gold, ivory, copper, pearls and coral.

Notice that the trajectory, as described, skips over nearly all the towns on the East African coast north of Mozambique – Kilwa (Quíloa), Zanzibar, Mombasa (Mombaça), Malindi (Melinde), Barawa (Brava), Mogadishu (Magadoxo), etc.

Plenty of experienced Indian Ocean pilots – Swahili, Arab or Gujarati – could be found in the city, and Malindi was likely to have the latest news from across the sea, so it was a very convenient stop for the Portuguese before a crossing.

The island was generally undersupplied – it contained only a few fishing villages – but the armada ships were often forced to sojourn there for long periods, usually for repair or to await for better winds to carry them down to Cochin.

Although Cochin, with its important spice markets, remained the ultimate destination, and was still the official Portuguese headquarters in India until the 1530s, Goa was more favorably located relative to Indian Ocean wind patterns and served as its military-naval center.

The Casa was in charge of monitoring the crown monopoly on India trade – receiving goods, collecting duties, assembling, maintaining and scheduling the fleets, contracting private merchants, correspondence with the feitorias (overseas factories), drafting documents and handling legal matters.

Separately from the Casa, but working in coordination with it, was the Armazém das Índias, the royal agency in charge of nautical outfitting, that oversaw the Lisbon docks and naval arsenal.

The Armazém was responsible for the training of pilots and sailors, ship construction and repair, and the procurement and provision of naval equipment – sails, ropes, guns, instruments and, most importantly, maps.

The piloto-mor ('chief pilot') of the Armazém, in charge of pilot-training, was, up until 1548, also the keeper of the Padrão Real, the secret royal master map, incorporating all the cartographic details reported by Portuguese captains and explorers, and upon which all official nautical charts were based.

[19] In the early Carreira da India, the carracks were usually accompanied by smaller caravels (caravelas), averaging 50–70 tons (rarely reaching 100), and capable of holding 20–30 men at most.

With a few exceptions (e.g. Flor de la Mar, Santa Catarina do Monte Sinai), Portuguese India naus were not typically built to last longer than four or five years of useful service.

Hulls were amply coated in pitch and pine tar (imported in bulk amounts from northern Germany), giving the India naus their famous (and, to some observers, sinister) dark tone.

The most famous of these was probably the mighty Portuguese carrack Santa Catarina (not to be confused with its earlier Mount Sinai namesake), captured in 1603, by Dutch captain Jacob van Heemskerk.

These included general instructions on how to read, plot and follow routes by nautical chart, how to use the principal nautical instruments of the day – the mariner's compass, the quadrant, the astrolabe, the nocturlabe and the balestilha (cross-staff) – and astronomical tables (notably that of solar declination, derived from Abraham Zacuto and later Pedro Nunes's own) to correctly account for "compass error" (the deviation of the magnetic north from the true north) by recourse to the Pole Star, Sun and Southern Cross, the flux and reflux of tides, etc.

As naval artillery was the single most important advantage the Portuguese had over rival powers in the Indian Ocean, gunners were highly trained and enjoyed a bit of an elite status on the ship.

The remainder is subsequently divided into three parts: 2/3 for the crown again (albeit to be expended on the armada itself in the form of equipment, supplies and ammunition), and the remaining third distributed among the crew for private taking.

The first Portuguese factory in Asia was set up in Calicut (Calecute, Kozhikode), the principal spice entrepot on the Malabar Coast of India in September 1500, but it was overrun in a riot a couple of months later.

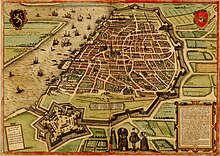

The intercontinental streams of spices, gold and silver flowing in and out of the Portuguese factory transformed Antwerp overnight from a sleepy town into arguably the leading commercial and financial center of Europe in the 16th century, a position it would enjoy until its sack by mutinous Spanish soldiers in 1576.

Most of the European leg of the trade was directly contracted between the Casa da Índia in Lisbon and private foreign consortiums (usually Italian and German) in Antwerp and freighted largely by Dutch, Hanseatic and Breton ships.

With this information in hand, the Dutch finally made their move in 1595, when a group of Amsterdam merchants formed the Compagnie van Verre and sent out their first expedition, under de Houtman, to the East Indies, aiming for the market port of Bantam.

The vigorous Dutch VOC and English EIC encroachments on the Portuguese empire and trade in Asia, prompted the monarchy (then in Iberian Union with Spain) to experiment with different arrangements.

[44] Of the unofficial accounts, Jerónimo Osório's De rebus Emmanuelis, is essentially a Latin restatement of the earlier chronicles, hoping for a wider European audience, and provides little that we don't already know.

Unlike Barros, Góis or Osório, Castanheda actually visited the East, spending ten years in India, and supplemented the archival material with independent interviews he conducted there and back in Coimbra.