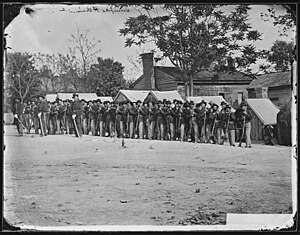

9th Indiana Infantry Regiment

Governor Oliver Hazard Perry Morton appointed Robert H. Milroy as colonel of the 9th on April 26, 1861, nearly two weeks after the firing began at the Battle of Fort Sumter.

[4][note 2] By the time the 9th was assigned to William B. Hazen's 19th Brigade of Buell's Army of the Ohio in March 1862, Colonel Gideon C. Moody, a former prosecutor and politician, commanded the regiment.

Photographs of some of these officers and a number of other officers and enlisted men from the 9th can be found at Indiana Civil War Soldiers, 9th Infantry,CITEREFCWI,_9th_Infantry_(2001)[note 3] The NPS System includes 816 troop records (three-month) and 2916 troop records (three-year) classified as 9th Regiment, Indiana Infantry.

[11] Soldiers from the 9th Indiana Infantry were among the first troops of Major General George B. McClellan’s Department of the Ohio to enter western Virginia in the spring of 1861.

[note 6] The battle began when a Federal battery started lobbing shells into a camp of around 825 and surprised Confederate recruits who had been asleep.

He recalled that visit and the battle in a 1904 piece written for the Eighth Annual Reunion of the 9th Indiana, noting that the Union battery involved "did nothing worse than take off a young Confederate's leg.

[16] As part of Morris' brigade, the 9th Indiana, taking cover behind trees, exchanged fire with Confederates, who were behind breastworks.

Tiring of the stalemate that ensued, the Union troops charged the breastworks and did "well enough, considering the hopeless folly of the movement," according to Ambrose Bierce.

The 9th along with the rest of Morris' brigade (including the Seventh Indiana and the 14th Ohio) pursued Garnett to Corrick's Ford.

To ensure the escape of most of his forces, Garnett ordered the 23rd Virginia Infantry to make a stand in a laurel thicket on the east side of Shaver's Fork at Corrick's Ford.

Morris' brigade successfully attacked and displaced the 23rd, and a member of the Seventh Indiana managed to shoot Garnett in the spine, killing him.

During a 1903 visit to the site, Bierce noted Union graves, most of which had been opened, with the bodies relocated to the National Cemetery at Grafton.

After a 1909 visit to the area, Bierce recounted the manner of Abbott's death, although he did not personally witness it: "He was lying flat upon his stomach and was killed by being struck in the side by a nearly spent cannon-shot that came rolling in among us.

It was a solid round-shot, apparently cast in some private foundry, whose proprietor, setting the laws of thrift above those of ballistics, had put his 'imprint' upon it; upon it: it bore, in slightly sunken letters, the name 'Abbott.

The 9th formed part of a brigade under their old regimental commander, now Brigadier General Robert H. Milroy, that attacked Col. Edward Johnson's forces protecting the Staunton-Parkersburg Pike.

They exchanged fire for a good portion of that morning, and the Confederates managed to force a Union retreat back to the Cheat Mountain camps.

But the Regular Army fellow had not the heart to suggest the demolition of our Towers of Babel, and the foundations remain to this day.

Once on a steamer riding precariously low in the water under the weight of the troops, the 9th had a closer view of two Union gunboats, the Lexington and the Tyler.

[23] During the night of April 6 and the early morning of the 7th, Buell positioned Nelson's division closest to the river of all the troops under his command.

On December 31, the 9th as part of Hazen's brigade defended the left flank of the Union line at Round Wood, now known as "Hell's Half Acre" because of the intensity of the battle at this location.

Hazen's forces were the only part of the original line to hold, despite a number of attacks by Breckenridge's division and reinforcements from Polk's corps.

[27] Ambrose Bierce, then a 2nd Lieutenant, documents the ferocity and sheer brutality of the battle in his famous short story "Chickamauga".