A Dictionary of the Chinese Language

[4] This groundbreaking reference work is enormous, comprising 4,595 pages in 6 quarto volumes and including 47,035 head characters taken from the 1716 Kangxi Dictionary.

[8] In 1807, the LMS instructed Morrison to sail to Guangzhou (then known as "Canton") and continue studying until he had "accomplished [his] great object of acquiring the language", whereupon he would "turn this attainment into a direction which may be of extensive use to the world: perhaps you may have the honour of forming a Chinese Dictionary, more comprehensive and correct than any preceding one", as well as translating the Bible into Chinese.

Morrison eventually found two tutors, the scholar "Ko Seen-sang" and Abel Yun, who had learned Latin from Catholic missionaries.

The situation worsened in 1812 when the Jiaqing Emperor issued an edict adding Christianity to the list of banned witchcrafts and superstitions, making the printing of Chinese-language books on the subject a capital crime.

All 6 volumes were printed by P. P. Thoms in Macao and published and sold by Black, Parbury, & Allen, the booksellers to the East India Company.

[17] The LMS was unable to subsidize the entire project, but the directors of the East India Company agreed to pay because they recognized the dictionary's incalculable benefit, not only to missionaries but also to their own employees.

The initial edition of 750 copies and subsequent reprints enabled Morrison's dictionary to reach a wider readership and have a far more profound impact.

For example, the American sinologist W. South Coblin analyzed Morrison's romanization of Mandarin for clues about the pronunciation of early 19th-century standard Chinese.

[34] Morrison's pronunciation glosses followed the lower Yangtze koiné as the standard Mandarin of the time, "what the Chinese call the Nanking Dialect, than the Peking".

Morrison acknowledged his debt to the Kangxi Dictionary in his introduction to Volume I, saying it "forms the ground work" of Part I,[38] including its arrangement, number of characters (47,035), and many of its definitions and examples.

Chinese scholars have found that the majority of the Kangxi dictionary's usage examples were taken from books before the 10th century and ignored vulgar forms and expressions.

[43] Philosophically, Morrison's dictionary departed from that ordered by the Kangxi Emperor by including not only the Confucian Four Books and Five Classics but many more items drawn from Taoist and Buddhist texts.

The internal Three, they call 氣之清神之靈精之潔靜裏分陰陽而精氣神同化於虛無… "The clear unmixed influence, the intelligence of spirit; the purity of essence; in the midst of quiescence separated the Yin and Yang.

[39] To illustrate Volume I's "grand scope" and "many surprises", Wu Xian & al. cited the 40-page entry for 學 (xue, "study; receive instruction; practice; imitate; learn; a place of studying")[46] whose usage examples and illustrations range across the traditional Chinese educational system from "private school" (學館, xueguan) to "government-run prefectural school" (府學, fuxue), explain the imperial examination civil service system from "county candidates" (秀才, xiucai) to "members of the imperial Hanlin Academy" (翰林, hanlin), and include a variety of related terms and passages such as 100 rules for schools, details on examination systems, and a list of books for classical study.

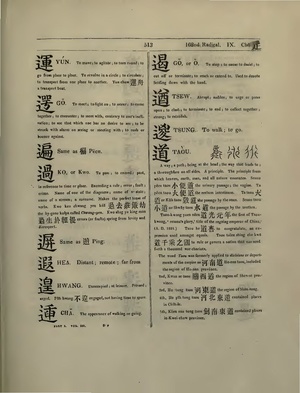

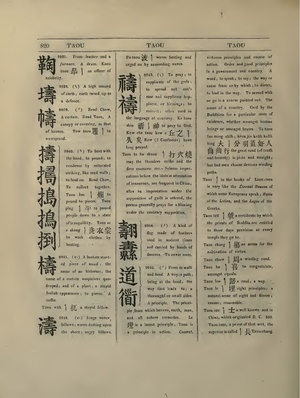

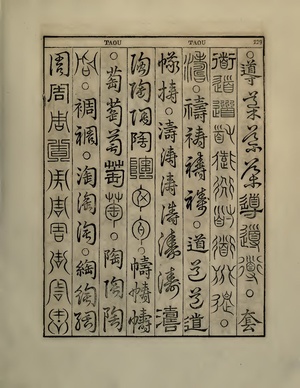

The regular script character and pronunciation are given alongside its small seal and cursive forms, followed by English translations, derived terms, and usage examples.

[52] Yang's comparative study of Parts I and II found, however, that the definitions of both are clearly based on the Kangxi Dictionary and reflect little content from original Wuche Yunfu.

Wu Xian & al. draw attention to his treatment of the character 仰 (yǎng, "look up; admire"), which now consists of Radical 9 (人, "person") and 卬 (áng, "high").

[48]The usage examples include words from Taoism and Buddhism: "Taou 道 in the books of Laou-tsze is very like the Eternal Reason of which some Europeans speak; Ratio of the Latins, and the Logos of the Greeks.

"; and using zhì (帙, "cloth case for a book"), "Taou těë 道帙 a certificate by which the priests of Buddha are entitled to three days provision at every temple they go to."

Considering that he was a self-taught lexicographer who compiled a dictionary of such a colossal size and scope, working with assistants who did not speak English, it would inevitably fall short of perfection, such the typographical errors and misprints noted above.

[15] In 1818 and again in 1830, the German orientalist Julius Klaproth accused Morrison of merely translating Chinese dictionaries rather than compiling a new or original one.

[66][67] In response to Klaproth's challenges, Morrison wrote an 1831 letter to the Asiatic Journal that describes the dictionary's compilation in detail.

[68]In retrospect, a "major flaw" in Morrison's dictionary is the failure to distinguish the phonemic contrast between aspirated and unaspirated consonants.

[69] Herbert Giles's Chinese-English Dictionary says Morrison's 1819 volume gave no aspirates, "a defect many times worse" than would be omitting the rough breathing in a Greek lexicon.

Another example is when he takes the 郎 in 招郎入室 to mean "bride"[72] when the intended sense is a "bridegroom" being invited to live with his in-laws.

[47] On the other hand, Morrison's Chinese dictionary has won critical acclaims from scholars all over the world since the publication of the first volume in 1815.

Alexander Leith Ross wrote to Morrison that his dictionary had an extensive circulation in Europe, and would be "an invaluable treasure to every student of Chinese".

[73] The French sinologist Stanislas Julien described Part II as "without dispute, the best Chinese Dictionary composed in a European language".

[76] Wu and Zheng say Morrison's was the first widely used Chinese-English dictionary and has served as a "milestone in the early promotion of communications between China and the West".

[77] Morrison's obituary notice summarizes his dedication and contribution to the world, "In efforts to make this [Chinese] language known to foreigners and chiefly to the English, he has done more than any other man living or dead."