Abakuá

Abakuá derives largely from the Ékpè society of West Africa, but displays adaptations like the inclusion of Roman Catholic symbolism.

The society teaches the existence of a supreme divinity named Abasí who supplied humanity with a form of power which holds a central place in Abakuá's origin myth.

Abakuá derives much from the Ékpè society, which was established by Efik people living around the Cross River basin of West Africa during the 18th century.

Through its membership, the society became increasingly influential in the stevedore, transportation, and local manufacturing industries of Cuba's ports, also attracting a reputation for criminal activity.

[11] In Cuba, practitioners of these traditions often see these different religions as offering complementary skills and mechanisms to solve problems.

[12] Thus, some Abakuá members also practice Palo,[13] or Santería,[14] or alternatively are babalawos, initiates in the divinatory system of Ifá.

[26] Abakuá draws heavily on the West African Ekpe society but also reflects innovations and developments that have taken place in Cuba.

[29] It revolves principally around how the god Abisi delivered a source of power, which was in the form of the fish Tanze, to two rival groups, the Efor and the Efik.

[29] In the story, the Efik then pressured the Efor to share the power with them, with seven members of each group meeting to sign an agreement; one individual refused, and this resulted in the thirteen major plazas within the society.

[4] The largest of these drums is called the bonkó enchemiyá; it is approximately 1 metre tall and placed at a slight tilt when being played.

[38] The three are tuned to produce different types of sound; that which reaches the highest pitch is the binkomé, the middle is the kuchí yeremá, and the lowest is the obiapá or salidor.

[38] As well as these four drums, the public rituals are typically accompanied with two rattles, the erikundí, and a bell made from two triangular pieces of iron, the ekón.

[29] The enkríkamo is used to convene the spirits of the dead, while the ekueñón is employed by the dignitary tasked with dispending justice and performing sacrifices, which the drum is expected to witness.

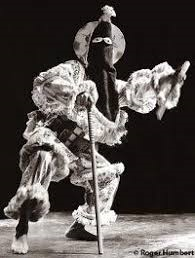

[41] For this they wear elaborate outfits consisting of checkerboard cloth, a design perhaps influenced by a leopard skin pattern.

[44] Abakuá was heavily influenced by the Ékpè society, which existed among the settlements of the Cross River basin in what is now Nigeria and Cameroon during the 18th and 19th centuries.

[45] Ékpè emerged among 18th-century Efik people as a means of transcending ethnic and family barriers and thus facilitating business relations for the trade in palm oil and slaves to European merchants.

[45] In Cuba, African slaves were divided into groups termed naciones (nations), often based on their port of embarkation rather than their own ethno-cultural background.

[50] The most important of these were the cabildos de nación, associations that the establishment regarded as a means of controlling the Afro-Cuban population.

[49] Although Efik people were transported to various parts of the Americas through the Atlantic slave trade, it was only in Cuba that there is evidence for the Ékpè society being reconstituted in any form.

"[49] The group's formation was supported by the Regla's Cabildo de Nación Carabalí Brícamo Appapá Efí.

[57] For over twenty years, Efik Buton and those in its lineage prohibited white and mulatto membership, seeking only those deemed to be of pure African blood.

"[60] The whites who joined were predominantly working class but also included high-ranking military figures, aristocrats, and politicians.

[57] The Efó branch, and also some Efí lodges, also admitted mulattos and those from additional migrant communities, including Canary Islanders, Chinese, and Filipinos.

[21] Abakuá members were among the Cubans who migrated to Florida in the late 19th century, many of them fleeing the Spanish government's crack down against perceived rebels.

[6] The Cuban Revolution of 1959 resulted in the island becoming a Marxist–Leninist state governed by Fidel Castro's Communist Party of Cuba.

[70] Following the Soviet Union's collapse in the 1990s, Castro's government declared that Cuba was entering a "Special Period" in which new economic measures would be necessary.

[75] In 2001, an Abakuá performance troupe appeared at a meeting of the Efik National Association of USA in Brooklyn, New York.

[24] The ethnomusicologist María Teresa Vélez suggested that Abakuá had been "discriminated against and persecuted more than other Afro-Cuban religious practices".

[76] Fernández Olmos and Paravisini-Gebert noted that the society had exerted a "profound and pervasive creative influence" on Cuban music, art, and language.

[78] Soto for instance used an Abakuá mask as a symbol for Cuba in a video-installation performance piece created in the early 21st century.