Spirituals

[7][8][9] While they were often rooted in biblical stories, they also described the extreme hardships endured by African Americans who were enslaved from the 17th century until the 1860s, the emancipation altering mainly the nature (but not continuation) of slavery for many.

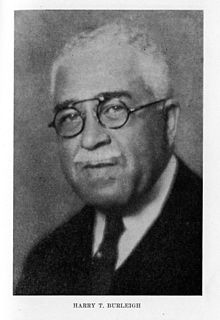

Black composers Harry Burleigh and R. Nathaniel Dett created a "new repertoire for the concert stage" by applying their Western classical education to the spirituals.

The LOC introductory sentence says, "A spiritual is a type of religious folksong that is most closely associated with the enslavement of African people in the American South.

Millions more remained enslaved in Africa, where slavery was a complex and deeply-rooted part of culture going back centuries before widespread European presence on the continent.

[4] Roughly 6% of all enslaved Africans transported via the trans-Atlantic slave trade arrived in the United States, both before and after the colonial era; the remainder went to Brazil, the West Indies or other regions.

[31] The first African enslaved people in what is now the United States arrived in 1526, making landfall in present-day Winyah Bay, South Carolina in a short-lived colony called San Miguel de Gualdape under control of the Spanish Empire.

"[38] His Narrative, which is the most famous of the stories written by former enslaved at that time, is one of the most influential pieces of literature that acted as a catalyst in the early years of the American abolitionist movement, according to the OCLC entry.

"Go Down Moses" referred to Harriet Tubman – that was her nickname—so that when they heard that song, they knew she was coming to the area...I often call the spiritual an omnibus term, because there are lots of different [subcategories] under it.

[16] Allen wrote that, it was almost impossible to convey the spirituals in print because of the inimitable quality of African American voices with its "intonations and delicate variations", where not "even one singer" can be "reproduced on paper".

"[16][46] In their 1925 book, The Books of American Negro Spirituals, James Weldon Johnson and Grace Nail Johnson said that spirituals, which are "purely and solely the creation" of African Americans, represent "America's only type of folk music...When it came to the use of words, the maker of the song was struggling under his limitations in language and, perhaps, also under a misconstruction or misapprehension of the facts in his source of material, generally the Bible.

"[2] The couple were active during the Harlem Renaissance James Weldon Johnson was the leader of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

"[49] According to a May 2012 PBS interview, "spirituals were religious folks songs, often rooted in biblical stories, woven together, sung, and passed along from one slave generation to another".

[50] Brown said that while other similarly-oppressed cultures were "virtually wiped out", the African slave survived because of spirituals by "singing through many of their problems", by creating their own "way of communicating".

[54]: 372 The spirituals provided some immunity protecting the African American religion from being colonized, and in this way preserved the "sacred as a potential space of resistance".

[58] The lyrics of Christian spirituals reference symbolic aspects of Biblical images such as Moses and Israel's Exodus from Egypt in songs such as "Michael Row the Boat Ashore".

Entitled Slave Songs of the United States, it was compiled by three northern abolitionists—Charles Pickard Ware (1840–1921), Lucy McKim Garrison (1842–1877), William Francis Allen (1830–1889)[16][65][Notes 4] The 1867 compilation built on the entire collection of Charles P. Ware, who had mainly collected songs at Coffin's Point, St. Helena Island, South Carolina, home to the African-American Gullah people originally from West Africa.

African American composers—Harry Burleigh, R. Nathaniel Dett, and William Dawson, created a "new repertoire for the concert stage" by applying their Western classical education to the spirituals.

[84][85] The Fisk Jubilee Singers continue to maintain their popularity in the 21st century with live performances in locations such as Grand Ole Opry House in 2019 in Nashville, Tennessee.

Arthur Jones founded "The Spirituals Project" at the University of Denver in 1999 to help keep alive the message and meaning of the songs that had moved from the fields of the South to the concert halls of the North.

[44] Numerous rhythmical and sonic elements of spirituals can be traced to African sources, including prominent use of the pentatonic scale (the black keys on the piano).

[44] In the 20th century, composers, such as Moses Hogan, Roland Carter, Jester Hairston, Brazeal Dennard and Wendell Whalum transformed the "cappella arrangements of spirituals for choruses" beyond its "traditional folk song roots".

[101][8][102][103]: 18 Jones described how during the years of the Underground Railroad "already existing spirituals" were employed "clandestinely" as one of the many ways people used in their "multilayered struggle for freedom.

[105][106] Other spirituals that some believe have coded messages include "The Gospel Train", "Song of the Free", and "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot", "Follow the Drinking Gourd".

[111] When the enslaved person sings, "I been rebuked, I been scorned; done had a hard time sho's you bawn," he is not only referring to freedom from sin but from physical bondage.

[92] Field hollers, cries and hollers of the enslaved people and later sharecroppers working in cotton fields, prison chain gangs, railway gangs (gandy dancers) or turpentine camps were the precursor to the call and response of African American spirituals and gospel music, to jug bands, minstrel shows, stride piano, and ultimately to the blues, rhythm and blues, jazz and African American music in general.

[117] The blues form originated in the 1860s in the Deep South—South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Tennessee, and Texas—states that were most dependent on the slave labor on planations and that held the largest number of enslaved people.

[119] The historical roots of the blues have been traced farther back to West African sources by scholars such as Paul Oliver[120] and Gerhard Kubik[121]—with elements such as the "responsorial 'leader-and-chorus' form".

[126]: 343–345 Bradford's African-American band, the Jazz Hounds, "played live, improvised", "unpredictable", "breakneck" music that was a "refreshing contrast to the buttoned-up versions of the blues interpreted by white artists across the 1910s".

According to Kubik, "the vocal style of many blues singers using melisma, wavy intonation, and so forth is a heritage of that large region of West Africa that had been in contact with the Arabic-Islamic world of the Maghreb since the seventh and eighth centuries.

[93] While many were pressured to convert to Christianity, the Sahelian slaves were allowed to maintain their musical traditions, adapting their skills to instruments such as the fiddle and guitar.