European witchcraft

[5][6] Some cultures have feared witchcraft much less than others, because they tend to have other explanations for strange misfortune; for example that it was caused by gods, spirits, demons or fairies, or by other humans who have unwittingly cast the evil eye.

[4]: 24-25 In these societies, practitioners of helpful magic provided services such as breaking the effects of witchcraft, healing, divination, finding lost or stolen goods, and love magic.<[4]: x-xi In Britain they were commonly known as cunning folk or wise people.

[20] Emma Wilby says folk magicians in Europe were viewed ambivalently by communities, and were considered as capable of harming as of healing, which could lead to their being accused as "witches" in the negative sense.

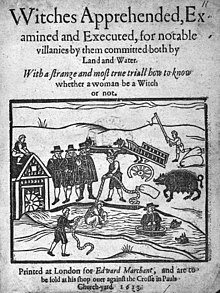

The Constitutio Criminalis Carolina (1532) of the Holy Roman Empire, and the Danish Witchcraft Act of 1617, stated that workers of folk magic should be dealt with differently from witches.

Deborah Willis adds, "The number of witchcraft quarrels that began between women may actually have been higher; in some cases, it appears that the husband as 'head of household' came forward to make statements on behalf of his wife".

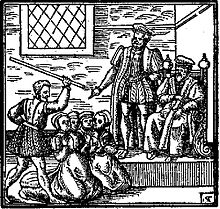

Not only were physicians and surgeons the principal professional arbiters for determining natural versus preternatural signs and symptoms of disease, they occupied key legislative, judicial, and ministerial roles relating to witchcraft proceedings.

These practitioners served on coroners' inquests, performed autopsies, took testimony, issued writs, wrote letters, or committed people to prison, in addition to diagnosing and treating patients.

[4]: 61 Hutton states that if even some portion were charged for killing with magical rites "then the Republican Romans hunted witches on a scale unknown anywhere else in the ancient world, and any other time in European history".

Thus, for example, the oldest document of Frankish legislation, the Salic law, which was reduced to a written form and promulgated under Clovis, who died 27 November, 511, punishes those who practice magic with various fines, especially when it could be proven that the accused launched a deadly curse, or had tied the Witch's Knot.

[citation needed] The Pactus Legis Alamannorum, an early 7th-century code of laws of the Alemanni confederation of Germanic tribes, lists witchcraft as a punishable crime on equal terms with poisoning.

The Council of Leptinnes in 744 drew up a "List of Superstitions", which prohibited sacrifice to saints and created a baptismal formula that required one to renounce works of demons, specifically naming Thor and Odin.

When Charlemagne imposed Christianity upon the people of Saxony in 789, he proclaimed: If anyone, deceived by the Devil, shall believe, as is customary among pagans, that any man or woman is a night-witch, and eats men, and on that account burn that person to death... he shall be executed.

[46] In 814, Louis the Pious upon his accession to the throne began to take very active measures against all sorcerers and necromancers, and it was owing to his influence and authority that the Council of Paris in 829 appealed to the secular courts to carry out any such sentences as the Bishops might pronounce.

The consequence was that from this time forward the penalty of witchcraft was death, and there is evidence that if the constituted authority, either ecclesiastical or civil, seemed to slacken in their efforts the populace took the law into their own hands with far more fearful results.

[citation needed] In England, the early Penitentials are greatly concerned with the repression of pagan ceremonies, which under the cover of Christian festivities were very largely practised at Christmas and on New Year's Day.

These rites were closely connected with witchcraft, and especially do S. Theodore, S. Aldhelm, Ecgberht of York, and other prelates prohibit the masquerade as a horned animal, a stag, or a bull, which S. Caesarius of Arles had denounced as a "foul tradition", an "evil custom", a "most heinous abomination".

[citation needed] Among the laws attributed to the Pictish King Cináed mac Ailpin (ruled 843 to 858), "is an important statute which enacts that all sorcerers and witches, and such as invoke spirits, 'and use to seek upon them for helpe, let them be burned to death'.

[48]The later Middle Ages saw words for these practitioners of harmful magical acts appear in various European languages: sorcière in French, Hexe in German, strega in Italian, and bruja in Spanish.

[citation needed] Hence the following law: We teach that every priest shall extinguish heathendom, and forbid wilweorthunga (fountain worship), and licwiglunga (incantations of the dead), and hwata (omens), and galdra (magic), and man worship, and the abominations that men exercise in various sorts of witchcraft, and in frithspottum (peace-enclosures) with elms and other trees, and with stones, and with many phantoms.While the common people were aware of the difference between witches, who they considered willing to undertake evil actions, such as cursing, and cunning folk who avoided involvement in such activities, the Church attempted to blot out the distinction.

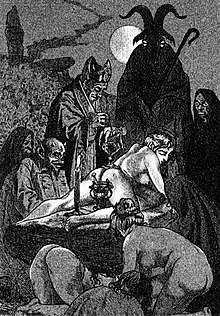

[57] The idea that witches gained their powers through a pact with the Devil provided a satisfactory explanation, and allowed authorities to develop a mythology through which they could project accusations of crimes formerly associated with various heretical sects (cannibalism, ritual infanticide, and the worship of demonic familiars) onto the newly emerging threat of diabolical witchcraft.

Custom provided a framework of responding to witches and witchcraft in such a way that interpersonal and communal harmony was maintained, Showing to regard to the importance of honour, social place and cultural status.

A person who claimed to have the power to call up spirits, or foretell the future, or cast spells, or discover the whereabouts of stolen goods, was to be punished as a vagrant and a con artist, subject to fines and imprisonment.

Ecclesiastical jurisdiction over witchcraft trials was established in the church, with origins dating back to early references in historical documents, such as the eleventh-century State Statute of Vladimir the Great and the Primary Chronicle.

Russia's approach to witchcraft trials showcased its unique blend of religious and social factors, culminating in a distinct historical context compared to the widespread witch hysteria observed in other parts of Europe.

Influenced by the now-discredited witch-cult hypothesis,[4]: 121 which suggested persecuted witches in Europe were followers of a surviving pagan religion, these traditions seek to reconnect with ancient beliefs and rituals.

The hypothesis received its most prominent exposition when it was adopted by a British Egyptologist, Margaret Murray, who presented her version of it in The Witch-Cult in Western Europe (1921), before further expounding it in books such as The God of the Witches (1931) and her contribution to the Encyclopædia Britannica.

Medieval accounts from writers including Joseph Glanvill and Johannes Nider describe the use of hallucinogenic concoctions, often referred to as ointments or brews, applied to sensitive areas of the body or objects like brooms for inducing altered states of consciousness.

These substances were believed to grant witches special abilities to commune with spirits, transform into animals, and participate in supernatural gatherings, forming a complex aspect of the European witchcraft tradition.

[145][146] A number of modern researchers have argued for the existence of hallucinogenic plants in the practice of European witchcraft; among them, anthropologists Edward B. Taylor, Bernard Barnett,[147] Michael J. Harner and Julio C. Baroja[148] and pharmacologists Louis Lewin[149] and Erich Hesse.

Many scholars attribute their manifestation in art as inspired by texts such as Canon Episcopi, a demonology-centered work of literature, and Malleus Maleficarum, a "witch-craze" manual published in 1487, by Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger.