Abdul Qadeer Khan

[6][7] Khan admitted his role in running a nuclear proliferation network – only to retract his statements in later years when he leveled accusations at the former administration of Pakistan's Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto in 1990, and also directed allegations at President Musharraf over the controversy in 2008.

[11][12] The United States reacted negatively to the verdict and the Obama administration issued an official statement warning that Khan still remained a "serious proliferation risk".

[25][26] From 1956 to 1959, Khan was employed by the Karachi Metropolitan Corporation (city government) as an Inspector of weights and measures, and applied for a scholarship that allowed him to study in West Germany.

[22] In 1962, while on vacation in The Hague, he met Hendrina "Henny" Reternik, a British passport holder who had been born in South Africa to Dutch expatriates.

[32] He worked under Belgian professor Martin J. Brabers at Leuven University, who supervised his doctoral thesis which Khan successfully defended, and graduated with a DEng in metallurgical engineering in 1972.

[33] In 1972, Khan joined the Physics Dynamics Research Laboratory (or in Dutch: FDO), an engineering firm subsidiary of Verenigde Machinefabrieken (VMF) based in Amsterdam, from Brabers's recommendation.

[49] Upon learning of India's surprise nuclear test, 'Smiling Buddha', in May 1974, Khan wanted to contribute to efforts to build an atomic bomb and met with officials at the Pakistani Embassy in The Hague, who dissuaded him by saying it was "hard to find" a job in PAEC as a "metallurgist".

[38]: 143–144 Later, Khan was advised by several officials in the Bhutto administration to remain in the Netherlands to learn more about centrifuge technology but continue to provide consultation on the Project-706 enrichment program led by Mahmood.

[38]: 143–144 By December 1975, Khan was given a transfer to a less sensitive section when URENCO became suspicious of his indiscreet open sessions with Mahmood to instruct him on centrifuge technology.

[38]: 147 In April 1976, Khan joined the atomic bomb program and became part of the enrichment division, initially collaborating with Khalil Qureshi – a physical chemist.

[54]: 62–63 Calculations performed by him were valuable contributions to centrifuges and a vital link to nuclear weapon research, but continue to push for his ideas for feasibility of weapon-grade uranium even though it had a low priority, with most efforts still aimed to produce military-grade plutonium.

[38]: 147–148 Khan became highly unsatisfied and bored with the research led by Mahmood – finally, he submitted a critical report to Bhutto, in which he explained that the "enrichment program" was nowhere near success.

[54]: 62–63 Upon reviewing the report, Bhutto sensed a great danger as the scientists were split between military-grade uranium and plutonium and informed Khan to take over the enrichment division from Mahmood, who separated the program from PAEC by founding the Engineering Research Laboratories (ERL).

[58] Many of his theorists were unsure that military-grade uranium would be feasible on time without the centrifuges, since Alam had notified PAEC that the "blueprints were incomplete" and "lacked the scientific information needed even for the basic gas-centrifuges.

However, they were riddled with serious technical errors, and while he bought some components for analysis, they were broken pieces, making them useless for quick assembly of a centrifuge.

[62] Intervention by the Chairman Joint Chiefs, General Jehangir Karamat, allowed Khan to be a participant and eye-witness his nation's first nuclear test, 'Chagai-I' in 1998.

[56] Many of Khan's colleagues were irritated that he seemed to enjoy taking full credit for something he had only a small part in, and in response, he authored an article, "Torch-Bearers", which appeared in The News International, emphasising that he was not alone in the weapon's development.

He made an attempt to work on the Teller–Ulam design for the hydrogen bomb, but the military strategists had objected to the idea as it went against the government's policy of minimum credible deterrence.

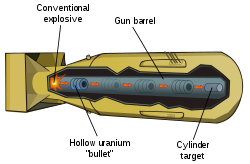

[68] In 1996, the U.S. intelligence community maintained that China provided magnetic rings for special suspension bearings mounted at the top of rotating centrifuge cylinders.

Iraqi officials said "the documents were authentic but that they had not agreed to work with A. Q. Khan, fearing an ISI sting operation, due to strained relations between two countries.

[89][90] Alfred Hempel, a German businessman, arranged the shipment of gas centrifuge parts from Khan in Pakistan to Libya and Iran via Dubai.

[94] Starting in 2001, Khan served as an adviser on science and technology in the Musharraf administration and had become a public figure who enjoyed much support from his country's political conservative sphere.

[81] On 4 February 2004, Khan appeared on Pakistan Television (PTV) and confessed to running a proliferation ring, and transferring technology to Iran between 1989 and 1991, and to North Korea and Libya between 1991 and 1997.

[99] While the local television news media aired sympathetic documentaries on Khan, the opposition parties in the country protested so strongly that the U.S. Embassy in Islamabad had pointed out to the Bush administration that the successor to Musharraf could be less friendly towards the United States.

[99] In 2007, the U.S. and European Commission politicians as well as IAEA officials had made several strong calls to have Khan interrogated by IAEA investigators, given the lingering scepticism about the disclosures made by Pakistan, but Prime Minister Shaukat Aziz, who remained supportive of Khan and spoke highly of him, strongly dismissed the calls by terming it as "case closed".

[101] In 2008, the security hearings were officially terminated by Chairman joint chiefs General Tariq Majid who marked the details of debriefings as "classified".

[8] In 2012, Khan also implicated Benazir Bhutto's administration in proliferation matters, pointing to the fact as she had issued "clear directions in thi[s] regard.

If (Pakistan) had an [atomic] capability before 1971, we [Pakistanis] would not have lost half of our country after a disgraceful defeat.During his work on the nuclear weapons program and onwards, Khan faced heated and intense criticism from his fellow theorists, most notably Pervez Hoodbhoy who contested his scientific understanding in quantum physics.

According to the editor-in-chief of Foreign Policy, Moisés Naím, although his actions were certainly ideological or political in nature, Khan's motives remain essentially financial.

[118] His wife, two daughters and brother Abdul Quyuim Khan were all named in the Panama Papers in 2016 as owners of Wahdat Ltd., an offshore company registered in the Bahamas.