Acacia

[1] The genus name is Neo-Latin, borrowed from the Greek ἀκακία (akakia), a term used in antiquity to describe a preparation extracted from Vachellia nilotica, the original type species.

The flowers are borne in spikes or cylindrical heads, sometimes singly, in pairs or in racemes in the axils of leaves or phyllodes, sometimes in panicles on the ends of branches.

The genus name comes from Neo-Latin; Gaspard Bauhin in his book Pinax (1623) writes it coming from Pedanius Dioscorides who uses the name ἀκακία akakia[13] for species Vachellia nilotica, the original type species growing in Egypt, from ἀκακίς akakis meaning "point".

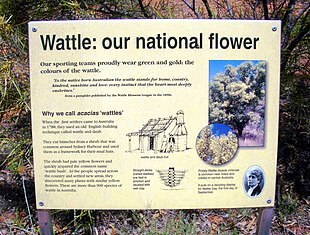

[15] From around 700 AD, watul was used in Old English to refer to the flexible woody vines, branches, and sticks which were interwoven to form walls, roofs, and fences.

Australian botanists proposed a less disruptive solution, setting a different type species for Acacia (A. penninervis) and allowing this largest number of species to remain in Acacia, resulting in the two pan-tropical lineages being renamed Vachellia and Senegalia, and the two endemic American lineages renamed Acaciella and Mariosousa.

[22][23] At the 2011 International Botanical Congress held in Melbourne, Australia, the decision to use the name Acacia, rather than the proposed Racosperma for this genus, was upheld.

in turn include the Australian and South East Asian genera Archidendron, Archidendropsis, Pararchidendron and Wallaceodendron, all of the tribe Ingeae.

[30] The oldest fossil Acacia pollen in Australia are recorded as being from the late Oligocene epoch, 25 million years ago.

[9][33] They are present in all terrestrial habitats, including alpine settings, rainforests, woodlands, grasslands, coastal dunes and deserts.

[40] Aboriginal Australians have traditionally harvested the seeds of some species, to be ground into flour and eaten as a paste or baked into a cake.

Wattleseeds contain as much as 25% more protein than common cereals, and they store well for long periods due to the hard seed coats.

[41] In addition to consuming the edible seed and gum, Aboriginal people also employed the timber for implements, weapons, fuel and musical instruments.

Black wattle bark supported the tanning industries of several countries, and may supply tannins for production of waterproof adhesives.