Academy

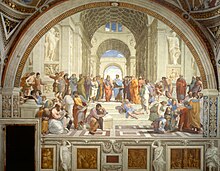

The name traces back to Plato's school of philosophy, founded approximately 386 BC at Akademia, a sanctuary of Athena, the goddess of wisdom and skill, north of Athens, Greece.

[4] The archaic name for the site was Hekademia, which by classical times evolved into Akademia and was explained, at least as early as the beginning of the 6th century BC, by linking it to an Athenian hero, a legendary "Akademos".

[5][6] Other notable members of Akademia include Aristotle, Heraclides Ponticus, Eudoxus of Cnidus, Philip of Opus, Crantor, and Antiochus of Ascalon.

According to the sole witness, the historian Agathias, its remaining members looked for protection under the rule of Sassanid king Khosrau I in his capital at Ctesiphon, carrying with them precious scrolls of literature and philosophy, and to a lesser degree of science.

After a peace treaty between the Persian and the Byzantine empire in 532 guaranteed their personal security (an early document in the history of freedom of religion), some members found sanctuary in the pagan stronghold of Harran, near Edessa.

The Musaeum, Serapeum and library of Alexandria Egypt was frequented by intellectuals from Africa, Europe and Asia studying various aspects of philosophy, language and mathematics.

Several cities developed centers of higher learning in the Sasanian Empire, including Mosul, al-Hira, and Harran (famous for the Pythagorean School of the Sabians).

It remained in place even after the new scholasticism of the School of Chartres and the encyclopedic work of Thomas Aquinas, until the humanism of the 15th and 16th centuries opened new studies of arts and sciences.

During the Florentine Renaissance, Cosimo de' Medici took a personal interest in the new Platonic Academy that he determined to re-establish in 1439, centered on the marvellous promise shown by the young Marsilio Ficino.

In Rome, after unity was restored following the Western Schism, humanist circles, cultivating philosophy and searching out and sharing ancient texts tended to gather where there was access to a library.

At the head of this movement for renewal in Rome was Cardinal Bessarion, whose house from the mid-century was the centre of a flourishing academy of Neoplatonic philosophy and a varied intellectual culture.

He was a worshipper not merely of the literary and artistic form, but also of the ideas and spirit of classic paganism, which made him appear a condemner of Christianity and an enemy of the Church.

Its principal members were humanists, like Bessarion's protégé Giovanni Antonio Campani (Campanus), Bartolomeo Platina, the papal librarian, and Filippo Buonaccorsi, and young visitors who received polish in the academic circle, like Publio Fausto Andrelini of Bologna who took the New Learning to the University of Paris, to the discomfiture of his friend Erasmus.

[24] In Naples, the Quattrocento academy founded by Alfonso of Aragon and guided by Antonio Beccadelli was the Porticus Antoniana, later known as the Accademia Pontaniana, after Giovanni Pontano.

The 16th century saw at Rome a great increase of literary and aesthetic academies, more or less inspired by the Renaissance, all of which assumed, as was the fashion, odd and fantastic names.

There were also the academy of the "Vignaiuoli", or "Vinegrowers" (1530), and the Accademia della Virtù [it] (1542), founded by Claudio Tolomei under the patronage of Cardinal Ippolito de' Medici.

As a rule these academies, all very much alike, were merely circles of friends or clients gathered around a learned man or wealthy patron, and were dedicated to literary pastimes rather than methodical study.

In the 17th century the tradition of literary-philosophical academies, as circles of friends gathering around learned patrons, was continued in Italy; the "Umoristi" (1611), the "Fantastici (1625), and the "Ordinati", founded by Cardinal Dati and Giulio Strozzi.

In its turn the state established Académie was the model for the Real Academia Española (founded in 1713) and the Swedish Academy (1786), which are the ruling bodies of their respective languages and editors of major dictionaries.

Although Prussia was a member of Holy Roman Empire, in 1700 Prince-elector Frederick III of Brandenburg founded its own Prussian Academy of Sciences upon the advice of Gottfried Leibniz, who was appointed president.

Starting at the end of the 16th century in the Holy Roman Empire, France, Poland and Denmark, many Knight academies were established to prepare the aristocratic youth for state and military service.

The École Militaire was founded by Louis XV of France in 1750 with the aim of creating an academic college for cadet officers from poor families.

In the early 19th century "academy" took the connotations that "gymnasium" was acquiring in German-speaking lands, of school that was less advanced than a college (for which it might prepare students) but considerably more than elementary.

[30] The Queen's Speech, which followed the 2010 general election, included proposals for a bill to allow the Secretary of State for Education to approve schools, both Primary and Secondary, that have been graded "outstanding" by Ofsted, to become academies.

In the beginning of the 19th century Wilhelm von Humboldt not only published his philosophical paper On the Limits of State Action, but also directed the educational system in Prussia for a short time.

In addition, academic institutions generally have an overall administrative structure (usually including a president and several deans) which is controlled by no single department, discipline, or field of thought.

Also, the tenure system, a major component of academic employment and research in the US, serves to ensure that academia is relatively protected from political and financial pressures on thought.

The Royal Society was steadfast in its unpopular belief that science could only move forward through a transparent and open exchange of ideas backed by experimental evidence.

In modern times, in the US and UK, gowns are normally only worn at graduation ceremonies, although some colleges still demand the wearing of academic dress on formal occasions (official banquets and other similar affairs).

We have to be extremely cautious in dealing with the literary evidence, because much of the information offered in the secondary literature on Taxila is derived from the Jataka prose that was only fixed in Ceylon several hundred years after the events that it purports to describe, probably some time after Buddhaghosa, i.e. around A.D. 500.