Balance of payments

[2] In the essays Of Money and Of the Balance of Trade, Hume argued that the accumulation of precious metals would create monetary inflation without any real effect on interest rates.

[3] According to historian Carroll Quigley, Great Britain could afford to act benevolently[5] in the 19th century due to the advantages of her geographical location, naval power, and economic ascendancy as the first nation to enjoy an Industrial Revolution.

A view advanced by economists such as Barry Eichengreen is that the first age of Globalization began with the laying of transatlantic telegraph cables in the 1860s, which facilitated a rapid increase in the already growing trade between Britain and America.

Deficit nations such as Great Britain found it harder to adjust by deflation as workers were more enfranchised and unions in particular were able to resist downwards pressure on wages.

There was a return to mercantilist type "beggar thy neighbour" policies, with countries competitively devaluing their exchange rates, thus effectively competing to export unemployment.

From the mid-1970s however, and especially in the 1980s and early 1990s, many other countries followed the US in liberalizing controls on both their capital and current accounts, in adopting a somewhat relaxed attitude to their balance of payments and in allowing the value of their currency to float relatively freely with exchange rates determined mostly by the market.

Typically but not always the panic among foreign creditors and investors that preceded the crises in this period was triggered by concerns over excess borrowing by the private sector, rather than by a government deficit.

[17][18] This new form of imbalance began to develop in part due to the increasing practice of emerging economies, principally China, in pegging their currency against the dollar, rather than allowing the value to freely float.

In the early to mid-1990s, many free market economists and policy makers such as U.S. Treasury secretary Paul O'Neill and Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan went on record suggesting the growing US deficit was not a major concern.

While several emerging economies had intervened to boost their reserves and assist their exporters from the late 1980s, they only began running a net current account surplus after 1999.

Mainstream opinion expressed by the leading financial press and economists, international bodies like the IMF – as well as leaders of surplus and deficit countries – has returned to the view that large current account imbalances do matter.

[36] Many Keynesian economists consider the existing differences between the current accounts in the eurozone to be the root cause of the Euro crisis, for instance Heiner Flassbeck,[37] Paul Krugman[38] or Joseph Stiglitz.

The conventional view is that current account factors are the primary cause[40] – these include the exchange rate, the government's fiscal deficit, business competitiveness, and private behaviour such as the willingness of consumers to go into debt to finance extra consumption.

[41] An alternative view, argued at length in a 2005 paper by Ben Bernanke, is that the primary driver is the capital account, where a global savings glut caused by savers in surplus countries, runs ahead of the available investment opportunities, and is pushed into the US resulting in excess consumption and asset price inflation.

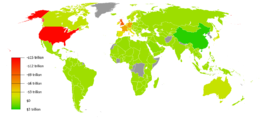

Global reserves rose sharply in the first decade of the 21st century, partly as a result of the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, where several nations ran out of foreign currency needed for essential imports and thus had to accept deals on unfavourable terms.

In a November 2009 article published in Foreign Affairs magazine, economist C. Fred Bergsten argued that Zhou's suggestion or a similar change to the international monetary system would be in the best interests of the United States as well as the rest of the world.

Conversely a downward shift in the value of a nation's currency makes it more expensive for its citizens to buy imports and increases the competitiveness of their exports, thus helping to correct a deficit (though the solution often doesn't have a positive impact immediately due to the Marshall–Lerner condition).

[55] Exchange rates can be adjusted by government[56] in a rules based or managed currency regime, and when left to float freely in the market they also tend to change in the direction that will restore balance.

While the gold standard is generally considered to have been successful[59] up until 1914, correction by deflation to the degree required by the large imbalances that arose after WWI proved painful, with deflationary policies contributing to prolonged unemployment but not re-establishing balance.

A possible method for surplus countries such as Germany to contribute to re-balancing efforts when exchange rate adjustment is not suitable, is to increase its level of internal demand (i.e. its spending on goods).

However, in 2009 Germany amended its constitution to prohibit running a deficit greater than 0.35% of its GDP[61] and calls to reduce its surplus by increasing demand have not been welcome by officials,[62] adding to fears that the 2010s would not be an easy decade for the eurozone.

[63] In their April 2010 world economic outlook report, the IMF presented a study showing how with the right choice of policy options governments can shift away from a sustained current account surplus with no negative effect on growth and with a positive impact on unemployment.

[65] Keynes suggested that traditional balancing mechanisms should be supplemented by the threat of confiscation of a portion of excess revenue if the surplus country did not choose to spend it on additional imports.

In 2008 and 2009, American economist Paul Davidson had been promoting his revamped form of Keynes's plan as a possible solution to global imbalances which in his opinion would expand growth all round without the downside risk of other rebalancing methods.

[75] In June 2009, Olivier Blanchard the chief economist of the IMF wrote that rebalancing the world economy by reducing both sizeable surpluses and deficits will be a requirement for sustained recovery.

The euro used by Germany is allowed to float fairly freely in value, however further appreciation would be problematic for other members of the currency union such as Spain, Greece and Ireland who run large deficits.

[80] China announced the end of the renminbi's peg to the US dollar in June 2010; the move was widely welcomed by markets and helped defuse tension over imbalances prior to the 2010 G-20 Toronto summit.

[82][83] In February 2011, Moody's analyst Alaistair Chan has predicted that despite a strong case for an upward revaluation, an increased rate of appreciation against the US dollar is unlikely in the short term.

Some economists such as Barry Eichengreen have argued that competitive devaluation may be a good thing as the net result will effectively be equivalent to expansionary global monetary policy.

An IMF report released after the summit warned that without additional progress there is a risk of imbalances approximately doubling to reach pre-crises levels by 2014.