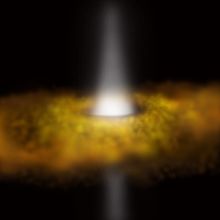

Accretion disk

Friction, uneven irradiance, magnetohydrodynamic effects, and other forces induce instabilities causing orbiting material in the disk to spiral inward toward the central body.

Gravitational and frictional forces compress and raise the temperature of the material, causing the emission of electromagnetic radiation.

The most prominent accretion disks are those of active galactic nuclei and of quasars, which are thought to be massive black holes at the center of galaxies.

The large luminosity of quasars is believed to be a result of gas being accreted by supermassive black holes.

[3] Elliptical accretion disks formed at tidal disruption of stars can be typical in galactic nuclei and quasars.

Angular momentum conservation prevents a straight flow from one star to the other and an accretion disk forms instead.

On one hand, it was clear that viscous stresses would eventually cause the matter toward the center to heat up and radiate away some of its gravitational energy.

[7][8] In 1991, with the rediscovery of the magnetorotational instability (MRI), S. A. Balbus, and J. F. Hawley established that a weakly magnetized disk accreting around a heavy, compact central object would be highly unstable, providing a direct mechanism for angular-momentum redistribution.

In the radiatively inefficient case, the disk may "puff up" into a torus or some other three-dimensional solution like an Advection Dominated Accretion Flow (ADAF).

Another extreme is the case of Saturn's rings, where the disk is so gas-poor that its angular momentum transport is dominated by solid body collisions and disk-moon gravitational interactions.

[13][14][15][16] Balbus and Hawley (1991)[9] proposed a mechanism which involves magnetic fields to generate the angular momentum transport.

A simple system displaying this mechanism is a gas disk in the presence of a weak axial magnetic field.

The inner fluid element is then forced by the spring to slow down, reduce correspondingly its angular momentum causing it to move to a lower orbit.

The outer fluid element being pulled forward will speed up, increasing its angular momentum and move to a larger radius orbit.

The magnetic fields present in astrophysical objects (required for the instability to occur) are believed to be generated via dynamo action.

[18] Accretion disks are usually assumed to be threaded by the external magnetic fields present in the interstellar medium.

These fields are typically weak (about few micro-Gauss), but they can get anchored to the matter in the disk, because of its high electrical conductivity, and carried inward toward the central star.

[20] High electric conductivity dictates that the magnetic field is frozen into the matter which is being accreted onto the central object with a slow velocity.

However, numerical simulations and theoretical models show that the viscosity and magnetic diffusivity have almost the same order of magnitude in magneto-rotationally turbulent disks.

In fact, a combination of different mechanisms might be responsible for efficiently carrying the external field inward toward the central parts of the disk where the jet is launched.

It is geometrically thin in the vertical direction (has a disk-like shape), and is made of a relatively cold gas, with a negligible radiation pressure.

Thin disks are relatively luminous and they have thermal electromagnetic spectra, i.e. not much different from that of a sum of black bodies.

The classic 1974 work by Shakura and Sunyaev on thin accretion disks is one of the most often quoted papers in modern astrophysics.

A fully general relativistic treatment, as needed for the inner part of the disk when the central object is a black hole, has been provided by Page and Thorne,[25] and used for producing simulated optical images by Luminet[26] and Marck,[27] in which, although such a system is intrinsically symmetric its image is not, because the relativistic rotation speed needed for centrifugal equilibrium in the very strong gravitational field near the black hole produces a strong Doppler redshift on the receding side (taken here to be on the right) whereas there will be a strong blueshift on the approaching side.

ADAFs started to be intensely studied by many authors only after their rediscovery in the early 1990s by Popham and Narayan in numerical models of accretion disk boundary layers.

[28][29] Self-similar solutions for advection-dominated accretion were found by Narayan and Yi, and independently by Abramowicz, Chen, Kato, Lasota (who coined the name ADAF), and Regev.

They are very radiatively inefficient, geometrically extended, similar in shape to a sphere (or a "corona") rather than a disk, and very hot (close to the virial temperature).

Credit: NASA/JPL-CaltechThe theory of highly super-Eddington black hole accretion, M≫MEdd, was developed in the 1980s by Abramowicz, Jaroszynski, Paczyński, Sikora, and others in terms of "Polish doughnuts" (the name was coined by Rees).

Polish doughnuts are low viscosity, optically thick, radiation pressure supported accretion disks cooled by advection.

Slim disks (name coined by Kolakowska) have only moderately super-Eddington accretion rates, M≥MEdd, rather disk-like shapes, and almost thermal spectra.