Event horizon

[1] In 1784, John Michell proposed that gravity can be strong enough in the vicinity of massive compact objects that even light cannot escape.

He eventually concluded that "the absence of event horizons means that there are no black holes – in the sense of regimes from which light can't escape to infinity.

This differs from the concept of the particle horizon, which represents the largest comoving distance from which light emitted in the past could reach the observer at a given time.

Define a comoving distance dp as In this equation, a is the scale factor, c is the speed of light, and t0 is the age of the Universe.

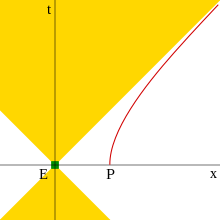

Under these conditions, an apparent horizon is present in the particle's (accelerating) reference frame, representing a boundary beyond which events are unobservable.

As the particle accelerates, it approaches, but never reaches, the speed of light with respect to its original reference frame.

While approximations of this type of situation can occur in the real world[citation needed] (in particle accelerators, for example), a true event horizon is never present, as this requires the particle to be accelerated indefinitely (requiring arbitrarily large amounts of energy and an arbitrarily large apparatus).

One of the best-known examples of an event horizon derives from general relativity's description of a black hole, a celestial object so dense that no nearby matter or radiation can escape its gravitational field.

Theoretically, any amount of matter will become a black hole if compressed into a space that fits within its corresponding Schwarzschild radius.

In practice, however, neither Earth nor the Sun have the necessary mass (and, therefore, the necessary gravitational force) to overcome electron and neutron degeneracy pressure.

If all the stars in the Milky Way would gradually aggregate towards the galactic center while keeping their proportionate distances from each other, they will all fall within their joint Schwarzschild radius long before they are forced to collide.

Astronomers can detect only accretion disks around black holes, where material moves with such speed that friction creates high-energy radiation that can be detected (similarly, some matter from these accretion disks is forced out along the axis of spin of the black hole, creating visible jets when these streams interact with matter such as interstellar gas or when they happen to be aimed directly at Earth).

Topologically, the event horizon is defined from the causal structure as the past null cone of future conformal timelike infinity.

[14][15][16] More precisely, one would need to know the entire history of the universe and all the way into the infinite future to determine the presence of an event horizon, which is not possible for quasilocal observers (not even in principle).

[17][18] In other words, there is no experiment and/or measurement that can be performed within a finite-size region of spacetime and within a finite time interval that answers the question of whether or not an event horizon exists.

Because of the purely theoretical nature of the event horizon, the traveling object does not necessarily experience strange effects and does, in fact, pass through the calculated boundary in a finite amount of its proper time.

Attempting to make an object near the horizon remain stationary with respect to an observer requires applying a force whose magnitude increases unboundedly (becoming infinite) the closer it gets.

In terms of visual appearance, observers who fall into the hole perceive the eventual apparent horizon as a black impermeable area enclosing the singularity.

In realistic stellar black holes, spaghettification occurs early: tidal forces tear materials apart well before the event horizon.

However, in supermassive black holes, which are found in centers of galaxies, spaghettification occurs inside the event horizon.