Achaemenid architecture

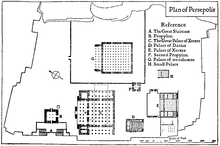

[6] Perhaps the most striking extant structures to date are the ruins of Persepolis, a once opulent city established by the Achaemenid king, Darius the Great for governmental and ceremonial functions, and also acting as one of the empire's four capitals.

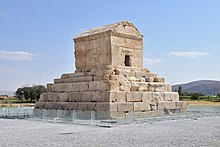

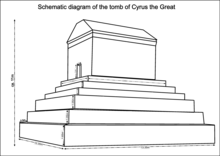

[11] Translated Greek accounts describe the tomb as having been placed in the fertile Pasargadae gardens, surrounded by trees and ornamental shrubs, with a group of Achaemenian protectors (the "Magi"), stationed nearby to protect the edifice from theft or damage.

[12][13] The magi were a group of on-site Zoroastrian observers, located in their separate but attached structure possibly a caravanserai, paid and cared for by the Achaemenid state (by some accounts they received a salary of daily bread and flour, and one sheep payment a day[14]).

[12] On some accounts, Alexander's decision to put the Magi on trial was more about his attempt to undermine their influence and his show of power in his newly conquered empire, than a concern for Cyrus's tomb.

[17] Mohammad Reza Pahlavi (Shah of Iran), the last official monarch of Persia, during his 2,500 year celebration of the Persian Empire paid significant homage to the Achaemenid kings and specially Cyrus the Great.

After the Iranian revolution, the tomb of Cyrus the Great survived the initial chaos and vandalism propagated by the Islamic revolutionary hardliners who equated Persian imperial historical artifacts with the late Shah of Iran.

The structure originally had an upper stone slab that in three different languages, (Old Persian, Elamite, Babylonian) declared, "I, (am) Cyrus the king, an Achaemenid.

[19] Noted Iranologist, Ilya Gershevitch explains this statement by Herodotus and its connection with the four winged figure in the following way:[19] Herodotus, therefore as I surmise, may have known of the close connection, between this type of winged figure, and the image of the Iranian majesty, which he associated with a dream prognosticating, the king's death, before his last, fatal campaign across the Oxus.This relief sculpture, in a sense depicts the eclectic inclusion of various art forms by the Achaemenids, yet their ability to create a new synthetic form that is uniquely Persian in style, and heavily dependent on the contributions of their subject states.

[16] Persepolis's prestige and grand riches were well known in the ancient world, and it was best described by the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus as "the richest city under the sun".

The columns in the porticoes have circular bases and are capped by ornate capitals after the end of the fluting, themselves topped by detailed addorsed bulls, supporting the roof.

In fact, the halls of Persepolis could at any one time host some ten thousand visitors easily, with the king and the royal staff seated appropriately.

As Persepolis was in essence an important cultural center often used by the beginning of the spring during the festival of Nowruz it enjoyed great precipitation and water runoffs from the molten ice and snow.

The second strategy was to divert water away from the structure should the reservoirs be filled to capacity; this system used a 180-meter-long conduit 7 m wide and 2.6 m deep located just west of the site.

Extensive use of stone in Persepolis, not only guaranteed its structural integrity for the duration of its use but also meant that its remains lasted longer than the mud-bricks of Susa palaces.

Excavations on behalf of the Oriental Institute of Chicago University, headed by Herzfeld in 1931 and later cooperation by Eric F. Schmidt in 1933 led to some of the most impressive uncovering of Achaemenid artifacts, palaces, and structures.

Herzfeld felt that the site of Persepolis was made for special ceremonies and was meant to convey the power of the Achaemenid empire to its subject nations.

[16] On some accounts, Persepolis was never officially finished as its existence was cut short by Alexander the Great, who in a fit of anger, ordered the burning of the city in 330 B.C.

Started originally by Darius the Great a century earlier, the structure was constantly changing, receiving upgrades from subsequent Persian monarchs, and undergoing renovation to maintain its impressive façade.

During this time period many western politicians, poets, artists, and writers were gravitated to Iran, and Persepolis, either as a function of the political relations with the Iranian monarchy or to report on, or visit the ruins.

[24] Despite this stern hatred, Alexander also admired the Persians as is obvious through his respect for Cyrus the Great, and his act of giving a dignified burial to Darius III.

[25]In retrospect, it must be understood that despite his momentary lapse of judgment and his role as having been the single most significant figure to bring an end to Persepolis, Alexander is not by any means the only.

[27] The first French excavation in Susa carried out by the Dieulafoys and the looting and the destruction of Persian antiquities by the so-called archeologists had a deep impact on the site.

After the Iranian revolution, a group of fundamentalists serving Khomeini, including his right-hand man Sadegh Khalkhali, tried to bulldoze both the renowned Persian poet, Ferdowsi's tomb, and Persepolis, but they were stopped by the provisional government.

"[6] French archaeologist, Egyptologist, and historian Charles Chipiez (1835–1901) has created some of the most advanced virtual drawings of what Persepolis would have looked like as a metropolis of the Persian Empire.

[16] What remains in way of structure from this once active capital, are five archaeological mounds, today located in modern Shush, in southwestern Iran, scattered over 250 hectares.

[30] Intricate scenes depicting archers of king Darius would decorate the walls, as well as motifs of nature such as double-bulls, unicorns, fasciae curling into volutes, and palms disposed as a flower or a bell.

[33] French archaeologist Marcel-Auguste Dieulafoy discovered the remnants of the palace of Darius, among the ruins of Susa producing the artifacts of this once magnificent structure now at display in the Louvre museum, France.

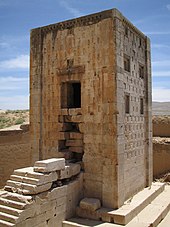

Structurally both "Jail of Solomon" and "Cube of Zoroaster" have the same cubic shape, and even resemble each other in the most minute of details, including facade, and dimensions.

[14] It should also be noted, that the structures as they exist today are not simply the work of the Achaemenid architects and have been modified, and improved by the Sassanids, who also used them for their festive, and political needs.

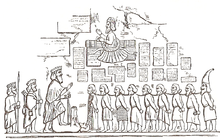

Architecturally speaking, the Behistun inscription is a massive project, that entailed cutting into the rough edge of the mountain in order to create bas-relief figures as seen in the pictures above.