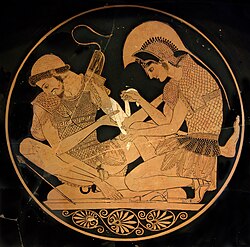

Achilles and Patroclus

In Book IX (lines 225 to 241) the diplomats, Odysseus and Ajax, hear Achilles playing the lyre and singing all alone with Patroclus.

The earlier steadfast and unbreakable Achilles agonizes, touching Patroclus' dead body, smearing himself with ash and fasting.

He returns to battle with the sole aim of avenging Patroclus' death by killing Hector, despite a warning that doing so would cost him his life.

Achilles' attachment to Patroclus is an archetypal male bond that occurs elsewhere in Greek culture: the mythical Damon and Pythias, the legendary Orestes and Pylades, and the historical Harmodius and Aristogeiton are pairs of comrades who gladly face danger and death for and beside each other.

[10] Writers that assumed a pederastic relationship between Achilles and Patroclus, such as Plato and Aeschylus, were then faced with a problem of deciding who must be older and play the role of the erastes.

[12] Specifically, according to Socrates: "Homer pictures us Achilles looking upon Patroclus not as the object of his passion but as a comrade, and in this spirit signally avenging his death".

"[14][15] Pindar's comparison of the adolescent boxer Hagesidamus and his trainer Ilas to Patroclus and Achilles in Olympian 10.16–21 (476 BC) as well as the comparison of Hagesidamus to Zeus' lover Ganymede in Olympian 10.99–105 suggest that student and trainer had a romantic relationship, especially after Aeschylus' depiction of Achilles and Patroclus as lovers in his play Myrmidons.

[16] In Plato's Symposium, written c. 385 BC, the speaker Phaedrus holds up Achilles and Patroclus as an example of divinely approved lovers.

[8] Xenophon cites other examples of legendary comrades, such as Orestes and Pylades, who were renowned for their joint achievements rather than any erotic relationship.

[18] Notably, in Xenophon's Symposium, the host Kallias and the young pankration victor Autolycos are called erastes and eromenos.

Aeschines, at his trial in 345 BC, placed an emphasis on the importance of paiderasteia to the Greeks, argues that though Homer does not state it explicitly, educated people should be able to read between the lines: "Although (Homer) speaks in many places of Patroclus and Achilles, he hides their love and avoids giving a name to their friendship, thinking that the exceeding greatness of their affection is manifest to such of his hearers as are educated men.

"[19] Most ancient writers (among the most influential Aeschylus, Plutarch, Theocritus, Martial and Lucian)[20] followed the thinking laid out by Aeschines.

[27] Achilles' decision to spend his days in his tent with Patroclus is seen by Odysseus (called Ulysses in the play) and many other Greeks as the chief reason for anxiety about Troy.

He argues that while a modern reader is inclined to interpret the portrayal of these intense same-sex male warrior friendships as being fundamentally homoerotic, it is important to consider the greater themes of these relationships: The thematic insistence on mutuality and the merging of individual identities, although it may invoke in the minds of modern readers the formulas of heterosexual romantic love [...] in fact situates avowals of reciprocal love between male friends in an honorable, even glamorous tradition of heroic comradeship: precisely by banishing any hint of subordination on the part of one friend to the other, and thus any suggestion of hierarchy, the emphasis on the fusion of two souls into one actually distances such a love from erotic passion.

[33] According to William A. Percy III, there are some scholars, such as Bernard Sergent, who believe that in Homer's Ionian culture there existed a homosexuality that had not taken on the form it later would in pederasty.

[1] Classicists Victor Davis Hanson and John Heath argue that modern authors who identify the pair as homosexual ingeniously reinvent the Homeric text at will.