Acrocanthosaurus

However, most of these remains are assigned to the species based on the assumption that Acrocanthosaurus is the only large carcharodontosaurid from North America during this time, and there exists the possibility that some referred specimens could represent distinct taxa.

As the name suggests, it is best known for the high neural spines on many of its vertebrae, which most likely supported a ridge of muscle over the animal's neck, back, and hips.

Recent discoveries have elucidated many details of its anatomy, allowing for specialized studies focusing on its brain structure and forelimb function.

The first (SMU 74646) is a partial skeleton, missing most of the skull, recovered from the Twin Mountains Formation of Texas and currently part of the Fort Worth Museum of Science and History collection.

[6] An even more complete skeleton (NCSM 14345, nicknamed "Fran") was recovered from the Antlers Formation of Oklahoma by Cephis Hall and Sid Love, prepared by the Black Hills Institute in South Dakota, and is now housed at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences in Raleigh.

[8] Unlike many other dinosaur genera, much less large theropods, Acrocanthosaurus inhabited both the western and eastern regions of the North American continent.

This skeleton, the most completely known theropod specimen from the formation despite its fragmentary nature, had been previously identified as an ornithomimosaur until this study, and also represents the smallest known individual of the genus.

The weight-reducing opening in front of the eye socket (antorbital fenestra) was quite large, more than a quarter of the length of the skull and two-thirds of its height.

Acrocanthosaurus and Giganotosaurus shared a thick horizontal ridge on the outside surface of the surangular bone of the lower jaw, underneath the articulation with the skull.

[19] The lower spines of Acrocanthosaurus had attachments for powerful muscles like those of modern bison, probably forming a tall, thick ridge down its back.

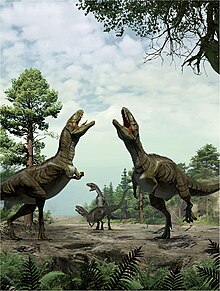

Acrocanthosaurus was bipedal, with a long, heavy tail counterbalancing the head and body, maintaining its center of gravity over its hips.

Unlike many smaller fast-running dinosaurs, its femur was longer than its tibia and metatarsals,[6][7] suggesting that Acrocanthosaurus was not a fast runner.

This superfamily is characterized by paired ridges on the nasal and lacrimal bones on top of the snout and tall neural spines on the neck vertebrae, among other features.

[18][21][22] At the time of its discovery, Acrocanthosaurus and most other large theropods were known from only fragmentary remains, leading to highly variable classifications for this genus.

J. Willis Stovall and Wann Langston Jr. first assigned it to the "Antrodemidae", the equivalent of the Allosauridae, but it was transferred to the Megalosauridae, a wastebasket taxon, by Alfred Sherwood Romer in 1956.

[27][28] Tall spined vertebrae from the Early Cretaceous of England were once considered to be very similar to those of Acrocanthosaurus,[29] and in 1988 Gregory S. Paul named them as a second species of the genus, A.

[31] Most cladistic analyses including Acrocanthosaurus have found it to be a carcharodontosaurid, usually in a basal position relative to Carcharodontosaurus of Africa and Giganotosaurus from South America.

[34] His results are shown below.Sauroniops Veterupristisaurus Lusovenator Concavenator Carcharodontosaurus iguidensis (holotype maxilla) Eocarcharia (referred maxilla) Carcharodontosaurus iguidensis (referred cranial material) Lajasvenator Labocania Carcharodontosaurus saharicus (described by Stromer in 1931) Tyrannotitan In the description of the carcharodontosaurid Tameryraptor, it is noted the specimen NCSM 14345 possesses several differences from the type specimen of Acrocanthosaurus atokensis, seen listed below: While beyond the scope of their paper, the authors note that these differences may be grounds for a reexamination of North American carcharodontosaurid material, and may suggest a much richer diversity than once thought.

Among other findings, the study suggested that, in a resting position, the forelimbs would have hung from the shoulders with the humerus angled backward slightly, the elbow bent, and the claws facing medially (inwards).

Another possibility is that Acrocanthosaurus held its prey in its jaws, while repeatedly retracting its forelimbs, tearing large gashes with its claws.

In 2005, scientists reconstructed an endocast (replica) of an Acrocanthosaurus cranial cavity using computed tomography (CT scanning) to analyze the spaces within the holotype braincase (OMNH 10146).

[37] The Glen Rose Formation of central Texas preserves many dinosaur footprints, including large, three-toed theropod prints.

[43] The famous Glen Rose trackway on display in New York City includes theropod footprints belonging to several individuals which moved in the same direction as up to twelve sauropod dinosaurs.

For example, several solitary theropods may have moved through in the same direction at different times after the sauropods had passed, creating the appearance of a pack stalking its prey.

[45] However, other scientists doubt the validity of this interpretation because the sauropod did not change gait, as would be expected if a large predator were hanging onto its side.

This indicates that the Twin Mountains Formation lies entirely within the Aptian stage, which lasted from 125 to 112 million years ago.

[18] During this time, the area preserved in the Twin Mountains and Antlers formations was a large floodplain that drained into a shallow inland sea.

[10] The Glen Rose Formation represents a coastal environment, with possible Acrocanthosaurus tracks preserved in mudflats along the ancient shoreline.

[43] Potential prey animals include sauropods like Astrodon[49] or possibly even the enormous Sauroposeidon,[50] as well as large ornithopod like Tenontosaurus.

[51] The smaller theropod Deinonychus also prowled the area but at 3 m (10 ft) in length, most likely provided only minimal competition, or even food, for Acrocanthosaurus.