Staghorn coral

It is characterized by thick, upright branches which can grow in excess of 2 meters (6.5 ft) in height and resemble the antlers of a stag, hence the name, Staghorn.

[6] Due to this fast growth, Acropora cervicornis, serve as one of the most important reef building corals, functioning as marine nurseries for juvenile fish, buffer zones for erosion and storms, and center points of biodiversity in the Western Atlantic.

It occurs in the western Gulf of Mexico, but is absent from U.S. waters in the Gulf of Mexico, as well as Bermuda and the west coast of South America; the northern limit of this species is Palm Beach County, Florida, where only small populations have been documented[10] Staghorn coral is most commonly found within 20 meters (65 ft) of the water's surface, in clear, non-turbid environments consistent with fore, back and patch reefs in the Western Atlantic Ocean.

[10] A fully grown and healthy colony could have potential hundreds of these branches, and achieve sizes up to and exceeding 2 meters (6.5 ft) in both height and width.

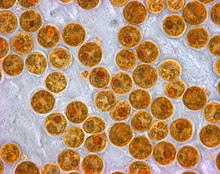

[4] Throughout millions of years of evolution, stony corals have formed a symbiotic relationship with 8 phylogenetic clades of dinoflagellate algae within the genus of Symbiodinium (also known as zooxanthellae).

[15] At the same time, the coral has become dependent on the dinoflagellates for up to 90% of their total nutritional requirements, which includes various lipids, amino acids, and sugars as well as a source of oxygenation and waste removal.

Using their long feeding tentacles, polyps are able to catch passing food, stunning it with their stinging nematocysts to prevent escape, eventually orientating it towards the mouth at the center for digestion.

[19] The contribution of nutrients gained from heterotrophy is poorly understood, however, it is thought that in stony corals, of which Staghorn is one, that it may account for anywhere from 0 to 66% of carbon fixation.

[21] Fragmentation can occur at anytime, and is usually the result of turbid flow from storms, nearby ships, dredging, or any disturbances in the water which would cause the breakage and successive replantation of coral branches.

Staghorn coral spawning is typically restricted to late summer, in the months of July and August and occurs several days following a full moon.

[23] The mechanism by which these corals choose a spawn day is still unknown, however, it is almost certainly influenced by a multitude of factors including water temperature, the lunar cycle, wave action and tidal periods.

Instead of drifting through the water aimlessly and attaching at a random point, coral planula have developed various key adaptations to aid in their search for the perfect home.

[26] As sponges grow uninhibited, they outcompete, smother and prevent the settlement of coral planula as they become the dominant habitat forming organisms on the reef.

[32] This increase in temperature has accelerated over the past decade, resulting in approximately 4.5 times greater ocean warming than the previous 100 years.

[36] On May 9, 2005, the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) determined that sufficient evidence existed to reclassify both the Staghorn (A. cervicornis), and the closely related Elkhorn (A. palmata), as threatened under the Endangered Species Act of 1973 (ESA).

[39] The main purpose of this plan was to rebuild the population and ensure its long-term viability with the ultimate goal of removal from the Endangered Species Act of 1973 (ESA).

[39] To achieve this removal, goals were put into place, including increasing the abundance of genetic diversity among both species throughout their geographical range, while at the same time identifying, reducing and/or eliminating threats to their survival, through both research and monitoring practices.

[39] A successful recovery plan for Staghorn coral must ensure populations increase to a size large enough to include many reproductively active colonies, with branches thick enough to provide ecosystem function and maintain genetic diversity.

[40] The goal of this designation was to address the key conservation objective when it came to the Staghorn coral, that is, to facilitate an increase in reproduction, both sexually and asexually.