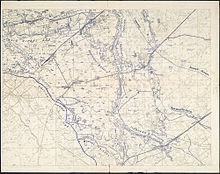

Action of 22 October 1917

Attacking on ground cut up by bombardments and soaked by rain, the British struggled to advance in places and lost the ability to move quickly to outflank pillboxes.

At a meeting on 13 October, Haig and the army commanders agreed that no more attacks could be made until the rain stopped and roads had been built to move forward the artillery and make bombardments more effective.

Haig wanted to continue the offensive until Passchendaele Ridge as far as Westroosebeek had been captured and to support the forthcoming French attack at La Malmaison, by keeping the Germans pinned down in Flanders.

The tactical sophistication of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) had increased during the battle but the chronic difficulty of communication between front and rear during an attack could not be resolved.

Due to the German system of pillbox defence and the impossibility of maintaining linear formations on ground full of flooded shell-craters, waves of infantry had been replaced by a thin line of skirmishers leading small columns.

[7] The Stellungsdivisionen held sectors that were too wide for swift replacement, because of the tempo of British attacks; Eingreif divisions had to be ready to swap places to enable frequent reliefs.

Divisional reliefs should be accomplished in one night; Eingreif divisions were to keep a third of their troops close to the front and the rest in reserve, only to advance to the battlefront after a British attack had started.

[10] The 4th Army HQ considered that the Allied advance in the north to be less dangerous than that towards Flandern II Stellung, the defensive position between Passchendaele and Drogenbroodhoek but a fresh division was moved to the area from Westrozebeke.

[11] Ludendorff changed his mind about holding Passchendaele Ridge, believing that the British had only fourteen days before the autumn weather ended the battle and ordered Rupprecht to stand fast.

Bombing raids were made on Abeele and Heule airfields and in dogfights with German fighters, ten aircraft were claimed shot down, for a loss of 19 British aircrew casualties.

After a two-hour pause, the second phase would begin, with three companies of the 10th Battalion Essex Regiment leap-frogging through the Norfolk positions, following a creeping barrage to the final objectives from Meunier House to Nobles Farm, 500 yd (460 m) beyond the Brewery.

If the attack succeeded, the third phase would begin with the fourth Essex company near Gloster Farm on the right flank, advancing to capture the Beek House blockhouse.

With no landmarks and deep mud, assembling at night and under German artillery-fire, the two battalions managed to deploy on a two-company front about 1,000 yd (910 m) wide from Aden House to Gravel Farm, with two companies in support.

[27] The attacking troops moved up to the front line on the night of 21/22 October, through the morass of the Steenbeek with respirators at the alert position on their heads, having already been bombarded with HE and gas shell.

German artillery-fire had increased, the dreadful condition of the ground made it difficult to vacate the area being bombarded and C Company arrived at the jumping-off position severely depleted, their weapons already jammed by mud.

A patrol went forward to Tracas Farm 200 yd (180 m) further on, which was empty but under British artillery-fire; a message to lift the fire was received quickly and a platoon occupied the position.

The 15th Royal Scots advanced on a two-company front from Gravel Farm and Turenne Crossing on the Ypres–Staden railway, towards the first objective 300 yd (270 m) away, near huts along by the Vijfwegen road and the Broenbeek.

The two support companies waited at Taube Farm, 700 yd (640 m) back and the attacking battalions were hit by machine-gun fire from several directions, particularly from pillboxes on the north bank of the Broenbeek.

German artillery-fire began after ten minutes but only a few shells landed near the attackers, sending up water spouts but Taube Farm was hit accurately and half of the two support companies were unable to move forward.

At 7:00 a.m., a German counter-attack was repulsed by rifle-fire but after holding on despite mounting casualties, the remaining 16th Royal Scots and Manchesters retreated to a point east of Egypt House.

Communication with the rear had been almost impossible, unburied telephone cables being cut early on, runners being slowed to a crawl by the mud and the area being bombarded continuously all day with HE and gas shell.

[32] The 104th Brigade battalions moved forward to tapes laid out in no man's land at 2:00 a.m. to evade the dawn bombardment by the German artillery of the British front line.

By noon, the brigade held a line from Maréchal Farm, a short stretch of Conter Drive and back to some huts 500 yd (460 m) to the north-east of Angle Point and thence to Aden House.

In the afternoon, patrols, often up to their waists in water, reached the fringes of Houthulst Forest, 1,100 yd (1,000 m) from the jumping-off point and captured two field guns and several prisoners.

[39] A British platoon had been provided for liaison with the 201st Infantry Regiment and when the French reached their objectives, Marindin sent two companies to form a defensive flank from Louvois Farm to Obtuse Bend.

At 2:00 a.m. on 23 October, a party of 22 men from the 20th Lancashire Fusiliers struggled through the mud to reach the position, which was 350 yd (320 m) beyond the wire that had blocked the advance of the 16th Royal Scots and the Manchester battalion, the day before.

[48] Poelcappelle had mainly been defended by artillery and the 18th (Eastern) Division captured the east end of the village ruins, where the Germans had repulsed two previous attacks.

[49] In 2014, Robert Perry wrote that the weather and the deplorable condition of the ground had led to the British infantry having to lie down cold and wet, in waterlogged shell-holes, under German bombardment.

Captured pillboxes and blockhouses were methodically bombarded by the German guns with HE and gas shell, making communication between the British front line and the rear almost impossible.

The creeping barrage moved forward too fast, rifles clogged with mud and the British fell back to the start line where they could or were surrounded by the Germans and overrun.