Mutilated victory

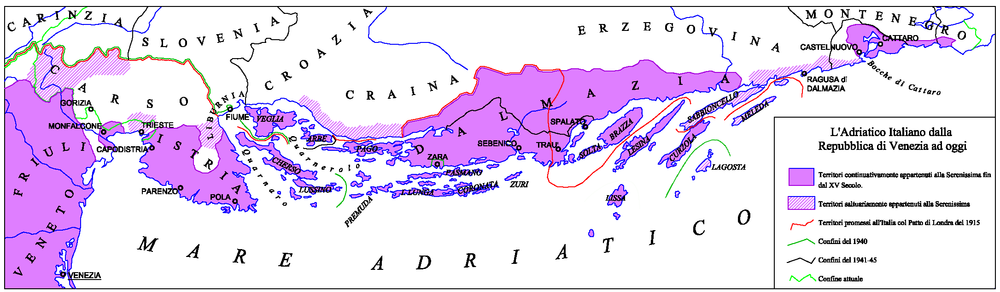

As a condition for entering the war against Austria-Hungary and Germany, Italy was promised, in the treaty of London signed in 1915 with the powers of the Triple Entente, recognition of control over Southern Tyrol, the Austrian Littoral and Dalmatia.

Italy completed the national unification of the country by annexing the provinces of Trento and Trieste, and also gained South Tyrol, Istria and some colonial compensations, but was not awarded Dalmatia, with the exception of the city of Zara.

While France and Britain remained bound by the treaty of London, the US president Woodrow Wilson (who joined the Allies in 1917) opposed it and presented on January 8, 1918 Fourteen Points to redraw the map of Europe on the basis of nationality and ethnicity.

A more substantial transfer of Dalmatian territories to Italy (favoured by Sonnino) was complicated to achieve because of its Slavic population, whereas Fiume was ethnically an Italian city (and as such proposed by Orlando as an alternative), but not included in the Pact of London.

[2] From a contemporary historical point of view, it has sometimes been observed how much of Benito Mussolini's foreign policy was presented as an attempt to amend the injustices lamented as stemming from the mutilated victory: Fiume was taken in 1924, Albania was turned into a client state under Zog I and merged into the Kingdom in 1939, and Dalmatia was annexed during the occupation of Yugoslavia—events that have been sporadically accused of prolonging Italy's participation in World War II.

Some historians have at times seen the actions carried by the Fascist government on the subject as part of a larger imperialist project that brought Italy to descend into foreign affairs, by intervening in Spain, conquering Ethiopia, and occupying southern France and Tunisia.

[3] Conversely, attempts to include in the Italian nation state the detached lands populated by Italophones have also been lauded and supported, with subjects failing to recognize said urgency being decried by poet Gabriele D’Annunzio as "insane and vile".

[4] Notwithstanding the political characterisations of the Interwar period, the final settlement of peace after the end of World War II, which had deprived Italy of all of the lands to the east of the Adriatic Sea (except for the city of Trieste), proved to be unpopular among the Italian opinion and object of harsh criticism, being described by President Luigi Einaudi as leading to a condition of "painfully mutilated" national unity.

In January 1917, British Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour wrote a letter to American President Woodrow Wilson expressing his disapproval of the promise to give Italy the Adriatic territories.

In a later trip to the United States in May to speak with American diplomat Edward M. House about the pact, Balfour made it clear that Britain had no particular ill will against Austria-Hungary and that the planned transfer of the Slavic lands to Italy would only create more problems.

The poet Gabriele D'Annunzio criticized in print and in speeches the failures of Prime Minister Vittorio Emanuele Orlando at the proceedings in Versailles, particularly in his attempts to acquire the city of Fiume (Croatian: Rijeka), which, notwithstanding the fact that its inhabitants were more than 90% ethnic Italians, was supposed to be ceded by Austria to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes.

Mussolini, an interventionist in World War I, attributed Italy’s great price of over 1.2 million casualties and 148 billion lire of expenditure to the weakness of the national government and to the disloyal attitude of the country’s former allies.