Robert Peary

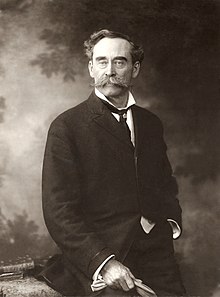

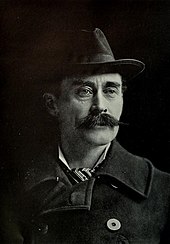

Robert Edwin Peary Sr. (/ˈpɪəri/; May 6, 1856 – February 20, 1920) was an American explorer and officer in the United States Navy who made several expeditions to the Arctic in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

[a] During an expedition in 1894, he was the first Western explorer to reach the Cape York meteorite and its fragments, which were then taken from the native Inuit population who had relied on it for creating tools.

During that expedition, Peary deceived six indigenous individuals, including Minik Wallace, into traveling to America with him by promising they would be able to return with tools, weapons and gifts within the year.

[6] After college, Peary worked as a draftsman making technical drawings at the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey office in Washington, D.C.

The second, more difficult path, was to start from Whale Sound at the top of the known portion of Baffin Bay and travel north to determine whether Greenland was an island or if it extended all the way across the Arctic.

In July, as Kite was ramming through sheets of surface ice, the ship's iron tiller suddenly spun around and broke Peary's lower leg; both bones snapped between the knee and ankle.

[7][9][10] Peary was unloaded with the rest of the supplies at a camp they called Red Cliff, at the mouth of MacCormick Fjord at the north west end of Inglefield Gulf.

[7] Unlike most previous explorers, Peary had studied Inuit survival techniques; he built igloos during the expedition and dressed in practical furs in the native fashion.

By wearing furs to preserve body heat and building igloos, he was able to dispense with the extra weight of tents and sleeping bags when on the march.

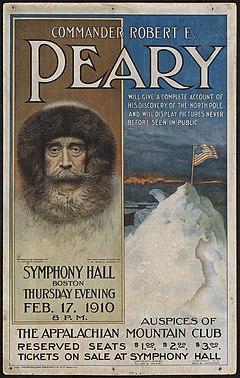

"[19] On December 15, 1906, the National Geographic Society of the United States, certified Peary's 1905–1906 expedition and "Farthest" with its highest honor, the Hubbard Medal.

The expedition used the "Peary system" for the sledge journey, with Bartlett and the Inuit, Poodloonah, "Harrigan," and Ooqueah, composing the pioneer division.

Peary states some of these observations were "beyond the Pole," and "...at some moment during these marches and counter-marches, I had passed over or very near the point where north and south and east and west blend into one.

"[20]: 287–298 [21]: 72–75 Henson scouted ahead to what was thought to be the North Pole site; he returned with the greeting, "I think I'm the first man to sit on top of the world," much to Peary's chagrin.

[24] Despite remaining doubts, a committee of the National Geographic Society, as well as the Naval Affairs Subcommittee of the U.S. House of Representatives, credited Peary with reaching the North Pole.

In early 1916, Peary became chairman of the National Aerial Coast Patrol Commission, a private organization created by the Aero Club of America.

[42] [43] Peary has also been harshly criticized for bringing back a group of Inughuit Greenlandic Inuit to the United States along with the Cape York meteorite.

[44] Working at the American Museum of Natural History, anthropologist Franz Boas had requested that Peary bring back an Inuit for study.

[45][46][47] During his expedition to retrieve the meteorite, Peary convinced six people, including a man named Qisuk and his child Minik, to travel to America with him by promising they would be able to return with tools, weapons and gifts within the year.

Our people were afraid to let them go, but Peary promised them that they should have Natooka and my father back within a year, and that with them would come a great stock of guns and ammunition, and wood and metal and presents for the women and children … We were crowded into the hold of the vessel and treated like dogs.

[1]Peary eventually helped Minik travel home in 1909, though it is speculated that this was to avoid any bad press surrounding his anticipated celebratory return after reaching the North Pole.

Convinced that the remains of Qisuk and the three adult Inuit should be returned to Greenland, he tried to persuade the Museum of Natural History to do this, as well as working through the "red tape" of the US and Canadian governments.

Peary had employed the Inughuit in his expeditions for more than a decade, paying them in firearms, ammunition and other Western goods on which they had come to rely, and leaving them in a dire situation in 1909.

This was further exacerbated by Peary's failure to produce records of observed data for steering, for the direction ("variation") of the compass, for his longitudinal position at any time, or for zeroing-in on the pole either latitudinally or transversely beyond Bartlett Camp.

[citation needed] The conflicting and unverified claims of Cook and Peary prompted Roald Amundsen to take extensive precautions in navigation during Amundsen's South Pole expedition so as to leave no room for doubt concerning his 1911 attainment of the South Pole, which—like Robert Falcon Scott's a month later in 1912—was supported by the sextant, theodolite, and compass observations of several other navigators.

Schweikart compared the reports and experiences of Japanese explorer Naomi Uemura, who reached the North Pole alone in 1978, to those of Peary and found they were consistent.

[54][2] In 1989, the NGS also conducted a two-dimensional photogrammetric analysis of the shadows in photographs and a review of ocean depth measures taken by Peary; its staff concluded that he was no more than 5 mi (8 km) away from the pole.

[55][26][56] Supporters of Peary and Henson assert that the depth soundings they made on the outward journey have been matched by recent surveys, and so their claim of having reached the Pole is confirmed.

[citation needed] In 2005, British explorer Tom Avery and four companions re-created the outward portion of Peary's journey using replica wooden sleds and Canadian Eskimo Dog teams.

Admiral Peary Vocational Technical School, located in a neighboring community very close to his birthplace of Cresson, PA, was named for him and was opened in 1972.

A section of U.S. Route 22 in Cambria County, Pennsylvania, is named the Admiral Peary Highway Major General Adolphus Greely, leader of the ill-fated Lady Franklin Bay Expedition from 1881 to 1884, noted that no Arctic expert questioned that Peary courageously risked his life traveling hundreds of miles from land, and that he reached regions adjacent to the pole.