Adolphe Thiers

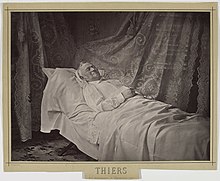

When he died in 1877, his funeral became a major political event; the procession was led by two of the leaders of the republican movement, Victor Hugo and Léon Gambetta, who at the time of his death were his allies against the conservative monarchists.

Historian Robert Tombs states it was, "A bold political act during the Bourbon Restoration...and it formed part of an intellectual upsurge of liberals against the counter-revolutionary offensive of the Ultra Royalists.

On 13 May 1797, his previous wife having died 2 months prior, his father married his mother Marie-Madeleine Amic, with Adolphe thereby becoming a legitimate child, undergoing a baptism by a refractory priest.

At the same time that Thiers began writing, his friend from the law school in Aix, Mignet, was hired as a writer for another leading opposition journal, the Courier Français, and then worked for a major Paris book publisher.

The British historian Thomas Carlyle, who wrote his own history of the French Revolution, complained that it "was far as possible from meriting its high reputation", though he admitted that Thiers is "a brisk man in his way, and will tell you much if you know nothing".

The historian George Saintsbury wrote in the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition (1911): "Thiers' historical work is marked by extreme inaccuracy, by prejudice which passes the limits of accidental unfairness, and by an almost complete indifference to the merits as compared with the successes of his heroes.

When the Constitutionel hesitated to publish some of his more energetic attacks on the government, Thiers, with Armand Carrel, Mignet, Stendhal and others, started a new opposition newspaper, the National, whose first issue appeared on 3 January 1830.

On 19 March 1830, he raised the temperature, warning that if the deputies put obstacles in his path, he would "find the force to overcome them in my resolution to maintain the public peace, with the full confidence of the French and the love they have also shown toward their King."

Without consulting with Louis-Philippe, whom he had never met, Thiers immediately had posters printed and put up around Paris declaring that the Duke of Orleans was a friend of the people, and he should take the crown.

In 1833, he was nominated for an open seat in the Académie française, based on his ten-volume history of the French Revolution, and other books he had written on the law and public finance, and the 1830 monarchy, and the Congress of Verona.

After 1833, his career was bolstered by his marriage to the daughter of his intimate friend, Madame Dosne, which allowed him to pay off his one hundred thousand franc loan from her father, finally giving him financial security.

His new government proposed the construction of the first railroad in France, from Paris to Saint-Germain (though Thiers privately described it as "A toy for the Parisians") and suppressed the national lottery on the grounds of morality.

When Thiers drafted a note to Britain warning that a British ultimatum to Egypt would upset the global balance of power, and he ordered construction of a new ring of fortresses around Paris.

A month later, he rose in Parliament to denounce the King's foreign policy, declaring that France had lost its influence in the Middle East, and had a duty to defend Egypt against Britain, and Turkey against Russia.

The book was criticized by Chateaubriand, who called it "an odious advertisement for Bonaparte, edited in the style of a newspaper" It had the unplanned effect of raising even further the prestige of Napoleon's nephew and Thiers' future enemy, Louis-Napoleon.

The day began peacefully, but by midday groups of demonstrators were raising barricades on the Champs-Élysées and hurling rocks at soldiers in front of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, at the corner of Boulevard des Capucines and rue Cambon.

"[26] The King reluctantly agreed, and sent for Thiers, but another event that evening changed the course of the Revolution; a unit of the army fired without orders on demonstrators outside the Ministry of Foreign Affairs on Boulevard des Capucines, killing sixteen and wounding dozens.

"[34] On economic policy, he was relentlessly conservative; he called for protectionism to defend French industry, and condemned the high cost of Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann's rebuilding of Paris, which had reached 461 million francs.

Thiers then followed the same plan that he had proposed to Louis-Philippe during the 1848 Revolution, but which the King had rejected; instead of fighting the insurrection immediately in Paris with the troops he had, he ordered regular army to withdraw to Versailles, to gather its forces, and then, when it was ready, to recapture the city.

While Thiers assembled his forces, including French soldiers just released from the German prison camps, Parisians elected a radical republican and socialist city government on 26 March: the Paris Commune.

The Assembly voted funds to rebuild his house on Place Saint-Georges in Paris, which had been burned by the Communards, and gave him money to replace his belongings, art collection, and library, which had been looted.

Thiers further won the support of the middle class and businessmen by opposing a proposed income tax, which he declared was entirely arbitrary, "inspired by political hatreds and passions."

Thiers signed a new convention with Germany on 15 March 1873, calling for the Germans to leave the last four French departments they held, Ardennes, Vosges, Meurthe-et-Moselle and Meuse by July 1873, two years ahead of schedule.

On 2 April, the moderate republican president of the Assembly, Jules Grévy, was forced to resign by a personal scandal and was replaced by a deputy of the center-right, Buffet, who supported a constitutional monarchy.

[55] The historian Jules Ferry described the funeral procession: "From rue Le Pelletier to Père Lachaise, a million people were packed in masses along the route of the cortege, standing up, hats off, saluting the casket, which was covered with mountains of flowers carried from all of France.

He brought back two mistresses from Italy, obtained another lucrative government post, from which he seems to have embezzled a large sum; he was chased down, arrested, but again released through the influence of Lucien Bonaparte.

He wrote: "Thiers' style is characterized by brilliant and dramatic descriptions and a liberal and tolerant spirit, but he is at times deficient in rigorous historical accuracy, and owing to the intense national feeling of the writer, his admiration for Napoleon sometimes gets the better of his judgement.

"[63] Thiers' account of the French invasion of Russia was sharply criticized by Leo Tolstoy for its factual inaccuracies and "general high-flown, pompous style, devoid of any direct meaning.

"[68] Another historian, Maxime du Camp wrote after Thiers' funeral: "Certainly people laughed at his contradictions, and during his lifetime he was not spared mockery, but he continued to be respected, because he passionately loved France.

"[70] The historian Pierre Guiral wrote in: "Adolphe Thiers, ou, De la nécessite en politique" in 1986: "He was a founder, the Washington of France, a man full of weaknesses but an uncontested patriot.