Affine transformation

In Euclidean geometry, an affine transformation or affinity (from the Latin, affinis, "connected with") is a geometric transformation that preserves lines and parallelism, but not necessarily Euclidean distances and angles.

An affine transformation does not necessarily preserve angles between lines or distances between points, though it does preserve ratios of distances between points lying on a straight line.

Examples of affine transformations include translation, scaling, homothety, similarity, reflection, rotation, hyperbolic rotation, shear mapping, and compositions of them in any combination and sequence.

Viewing an affine space as the complement of a hyperplane at infinity of a projective space, the affine transformations are the projective transformations of that projective space that leave the hyperplane at infinity invariant, restricted to the complement of that hyperplane.

If the dimension of X is at least two, a semiaffine transformation f of X is a bijection from X onto itself satisfying:[3] These two conditions are satisfied by affine transformations, and express what is precisely meant by the expression that "f preserves parallelism".

This identification permits points to be viewed as vectors and vice versa.

Formally, in the finite-dimensional case, if the linear map is represented as a multiplication by an invertible matrix

can be represented as Using an augmented matrix and an augmented vector, it is possible to represent both the translation and the linear map using a single matrix multiplication.

The technique requires that all vectors be augmented with a "1" at the end, and all matrices be augmented with an extra row of zeros at the bottom, an extra column—the translation vector—to the right, and a "1" in the lower right corner.

This representation exhibits the set of all invertible affine transformations as the semidirect product of

The advantage of using homogeneous coordinates is that one can combine any number of affine transformations into one by multiplying the respective matrices.

Suppose you have three points that define a non-degenerate triangle in a plane, or four points that define a non-degenerate tetrahedron in 3-dimensional space, or generally n + 1 points x1, ..., xn+1 that define a non-degenerate simplex in n-dimensional space.

The unique augmented matrix M that achieves the affine transformation

For example, if the affine transformation acts on the plane and if the determinant of

Such transformations form a subgroup called the equi-affine group.

[13] A transformation that is both equi-affine and a similarity is an isometry of the plane taken with Euclidean distance.

Each of these groups has a subgroup of orientation-preserving or positive affine transformations: those where the determinant of

In the last case this is in 3D the group of rigid transformations (proper rotations and pure translations).

For example, describing a transformation as a rotation by a certain angle with respect to a certain axis may give a clearer idea of the overall behavior of the transformation than describing it as a combination of a translation and a rotation.

The word "affine" as a mathematical term is defined in connection with tangents to curves in Euler's 1748 Introductio in analysin infinitorum.

[15] Felix Klein attributes the term "affine transformation" to Möbius and Gauss.

[10] In their applications to digital image processing, the affine transformations are analogous to printing on a sheet of rubber and stretching the sheet's edges parallel to the plane.

This transform relocates pixels requiring intensity interpolation to approximate the value of moved pixels, bicubic interpolation is the standard for image transformations in image processing applications.

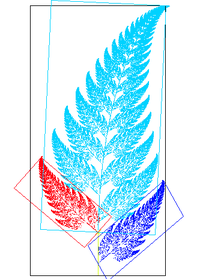

Affine transformations scale, rotate, translate, mirror and shear images as shown in the following examples:[16] The affine transforms are applicable to the registration process where two or more images are aligned (registered).

However, the affine transformations do not facilitate projection onto a curved surface or radial distortions.

Affine transformations in two real dimensions include: To visualise the general affine transformation of the Euclidean plane, take labelled parallelograms ABCD and A′B′C′D′.

Whatever the choices of points, there is an affine transformation T of the plane taking A to A′, and each vertex similarly.

Supposing we exclude the degenerate case where ABCD has zero area, there is a unique such affine transformation T. Drawing out a whole grid of parallelograms based on ABCD, the image T(P) of any point P is determined by noting that T(A) = A′, T applied to the line segment AB is A′B′, T applied to the line segment AC is A′C′, and T respects scalar multiples of vectors based at A.

Affine transformations do not respect lengths or angles; they multiply area by a constant factor A given T may either be direct (respect orientation), or indirect (reverse orientation), and this may be determined by its effect on signed areas (as defined, for example, by the cross product of vectors).

, the transformation shown at left is accomplished using the map given by: Transforming the three corner points of the original triangle (in red) gives three new points which form the new triangle (in blue).