The Holocaust in Slovakia

The Holocaust in Slovakia was the systematic dispossession, deportation, and murder of Jews in the Slovak Republic, a client state of Nazi Germany, during World War II.

After the September 1938 Munich Agreement, Slovakia unilaterally declared its autonomy within Czechoslovakia, but lost significant territory to Hungary in the First Vienna Award, signed in November.

Between March and October 1942, 58,000 Jews were deported to Auschwitz concentration camp and the Lublin District of the General Governorate; only a few hundred survived until the end of the war.

[5][6] Due to the schism in Hungarian Jewry, communities split in the mid-nineteenth century into Orthodox (the majority), Status Quo, and more assimilated Neolog factions.

Jews spearheaded the nineteenth-century economic changes that led to greater commerce in rural areas; by the end of the century some 70 percent of the bankers and businessmen in the Slovak uplands were Jewish.

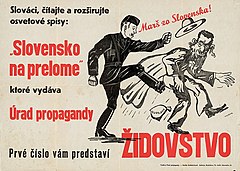

[23][24] HSĽS consolidated its power by passing an enabling act, banning opposition parties, shutting down independent newspapers, distributing antisemitic and anti-Czech propaganda, and founding the paramilitary Hlinka Guard.

[45] In his first radio address following the establishment of the Slovak State in 1939, Tiso emphasized his desire to "solve the Jewish Question";[46] anti-Jewish legislation was the only concrete measure that he promised.

[49] Adolf Eichmann, a Nazi official who had been sent to Bratislava, coauthored a plan with Tiso and other HSĽS politicians to deport impoverished and foreign Jews to the territory ceded to Hungary.

The state failed to raise substantial funds from the sale of Jewish property and businesses, and most of its gains came from the confiscation of Jewish-owned bank accounts and financial securities.

The main beneficiaries of Aryanization were members of Slovak fascist political parties and paramilitary groups, who were eager to acquire Jewish property but had little expertise in running businesses.

[101][103] The first leader of the ÚŽ was Heinrich Schwartz, who thwarted anti-Jewish orders to the best of his ability: he sabotaged a census of Jews in eastern Slovakia which was intended to justify their removal to the west of the country; Wisliceny had him arrested in April 1941.

[107] Wisliceny set up a Department for Special Affairs in the ÚŽ to ensure the prompt implementation of Nazi decrees, appointing the collaborationist Karol Hochberg (a Viennese Jew) as its director.

[95][110] Although the ÚŽ had to supplement the workers' pay to meet the legal minimum, the labor camps greatly increased the living standard of Jews impoverished by Aryanization.

[64][114] In mid-1941, as the focus shifted to restricting Jews' civil rights after they had been deprived of their property through Aryanization, Department 14 of the Ministry of the Interior was formed to enforce anti-Jewish measures.

[126][132] Both bishop Karol Kmeťko and papal chargé d'affaires Giuseppe Burzio confronted the president with reliable reports of the mass murder of Jewish civilians in Ukraine.

[147] The Slovak government agreed to pay 500 Reichsmarks per deportee (ostensibly to cover shelter, food, retraining and housing)[147][148] and an additional fee to the Deutsche Reichsbahn for transport.

[147][159] Slovak officials promised that deportees would be allowed to return home after a fixed period,[160] and many Jews initially believed that it was better to report for deportation rather than risk reprisals against their families.

[164] Reinhard Heydrich, the head of the Reich Security Main Office,[169] visited Bratislava on 10 April, and he and Tuka agreed that further deportations would target whole families and eventually remove all Jews from Slovakia.

[172][173] During the first half of June 1942 ten transports stopped briefly at Majdanek, where able-bodied men were selected for labor; the trains continued to Sobibor extermination camp, where the remaining victims were murdered.

Its leaders, Zionist organizer Gisi Fleischmann and Orthodox rabbi Michael Dov Weissmandl, bribed Anton Vašek, head of Department 14, and Wisliceny.

[226][214][h] The halt in deportations from Slovakia enabled the Working Group to launch the Europa Plan, an unsuccessful effort to bribe SS chief Heinrich Himmler to spare the surviving Jews under German occupation.

[238] In response to the threatened resumption, Slovak bishops issued a pastoral letter in Latin on 8 March condemning antisemitism and totalitarianism and defending the rights of all Jews.

[275] Anti-Jewish legislation in the liberated areas was canceled by the Slovak National Council,[243] but the attitude of the local population varied: some risked their lives to hide Jews, and others turned them in to the police.

[276][287] Half of Bratislava was on its feet this morning to watch the show of the Judenevakuierung ... so was the kick, administered by an S.S.-man to a tardy Jew received by the large crowd ... with hand claps and cries of support and encouragement.

The largest roundup was carried out in the city during the night of 28/29 September by Einsatzkommando 29, aided by 600 HS and POHG collaborators and a Luftwaffe unit that guarded the streets: around 1,600 Jews were arrested and taken to Sereď.

Although there were no transports until the end of September, the Jews experienced harsh treatment (including rape and murder) and severe overcrowding as the population swelled to 3,000 – more than twice the intended capacity.

[321][322] Both Tiso and Tuka were tried under Decree 33/1945, an ex post facto law that mandated the death penalty for the suppression of the Slovak National Uprising;[323][324] their roles in the Holocaust were a subset of the crimes for which they were convicted.

[334][335] Following the 1968 Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia, authorities cracked down on free expression,[336][337] while anti-Zionist propaganda, much of it imported from the Soviet Union, intensified and veered into antisemitism after Israeli victory in the 1967 Six-Day War.

[345] As of January 2019[update], Yad Vashem (the official Israeli memorial to the Holocaust) has recognized 602 Slovaks as Righteous Among the Nations for risking their lives to save Jews.

[54][139] A 1997 textbook by Milan Stanislav Ďurica and endorsed by the government sparked international controversy (and was eventually withdrawn from the school curriculum) because it portrayed Jews as living happily in labor camps during the war.