Aging of Japan

[6] The Japanese government has responded to concerns about the stresses demographic changes place on the economy and social services with policies intended to restore the fertility rate as well as increase the activity of the elderly in society.

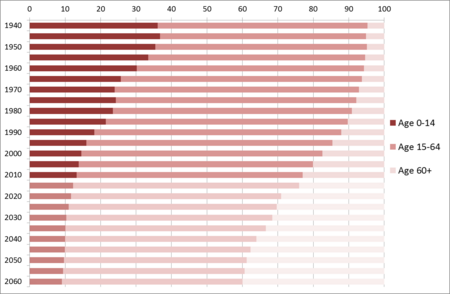

[12] This change in the demographic makeup of Japanese society, referred to as population ageing (kōreikashakai, 高齢化社会),[13] has taken place in a shorter period of time than in any other country.

Peace and prosperity following World War II were integral to the massive economic growth of post-war Japan, contributing further to the population's longevity.

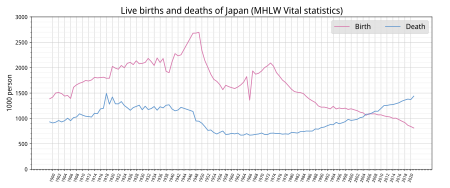

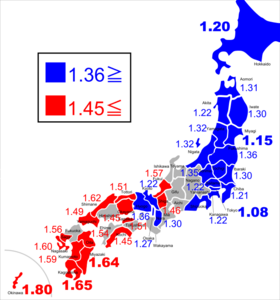

[23] Japan's total fertility rate, or TFR, the number of children born from each woman in her lifetime, has remained below the replacement threshold of 2.1 since 1974, and reached a historic low of 1.26 in 2005.

[20] Experts believe that signs of a slight recovery reflect the expiration of a "tempo effect," arising from a shift in the timing of children being born rather than any positive change.

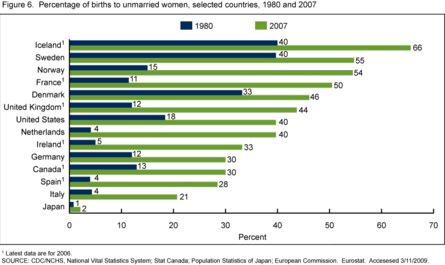

[25] A range of economic and cultural factors contributed to the decline in childbirth during the late 20th century: later and fewer marriages, higher education, urbanization, increase in nuclear family households (rather than the extended family), poor work-life balance, increased participation of women in the workforce, a decline in wages and lifetime employment, small living spaces and the high cost of raising a child.

[38] The Japanese sociologist Masahiro Yamada coined the term parasite singles (パラサイトシングル, parasaito shinguru) for unmarried women in their late 20s and 30s who continue to live with their parents.

[46] A smaller population could make the country's crowded metropolitan areas more livable, and the stagnation of economic output might still benefit a shrinking workforce.

However, low birth rates and high life expectancy have also inverted the standard population pyramid, forcing a narrowing base of young people to provide and care for a bulging older cohort, even as they try to form families of their own.

[53] During the first half of 2024, the National Police Agency reported that 37,227 individuals living alone were found dead at home, with 70% of these being aged 65 and above, and nearly 4,000 bodies discovered more than a month after death, including 130 that remained unnoticed for at least a year.

[54] The disposable income in Japan's older population has increased business in biomedical technologies research in cosmetics and regenerative medicine.

[5] The Greater Tokyo Area is virtually the only locality in Japan to see population growth, mostly due to internal migration from other parts of the country.

[58] Internal migration and population decline have created a severe regional imbalance in electoral power, where the weight of a single vote depends on where it was cast.

In 2014, the Supreme Court of Japan declared that the disparities in voting power violates the Constitution, but the ruling Liberal Democratic Party, which relies on rural and older voters, has been slow to make the necessary realignment.

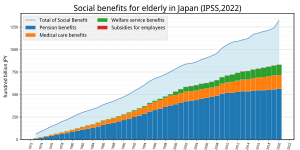

As recently as the early 1970s, the cost of public pensions, healthcare, and welfare services for the aged amounted to only about 6% of Japan's national income.

A study by the UN Population Division in 2000 found that Japan would need to raise its retirement age to 77 (or allow net immigration of 17 million by 2050) to maintain its worker-to-retiree ratio.

[5] The decline in working-aged cohorts may lead to a shrinking economy if productivity does not increase faster than the rate of Japan's decreasing workforce.

The increase is said to arise from day-care centers near or inside train stations, which are without waiting lists, and co-working spaces that include childcare rooms.

The Okinawan culture also emphasises a form of mutual aid called yuimaru, with relatives living close together to help family members with childrearing.

[85][88] However, "Womenomics", the set of policies intended to bring more women into the workplace as part of Prime Minister Shinzō Abe's economic recovery plan, has struggled to overcome cultural barriers and entrenched stereotypes.

[91] A net decline in population due to a historically low birth rate has raised the issue of immigration as a way to compensate for labor shortages.

[92][93] Professor Noriko Tsuya, of Keio University, states that it is not realistic to combat Japan's low birthrate with the increase of immigration.

The government has also expanded options available for international students, allowing them to begin work and potentially stay in Japan to help the economy.

Existing initiatives such as the JET Program encourage English-speaking people from across the world to work in Japan as English language teachers.

[105] In contrast to Japan, a more open immigration policy has allowed Australia, Canada, and the United States to grow their workforce despite low fertility rates.

[78] An expansion of immigration is often rejected as a solution to population decline by Japan's political leaders and people for reasons including the fear of foreign crime and a desire to preserve cultural traditions.

[107] Historically, European countries have had the largest elderly populations by proportion as they became developed nations earlier, experiencing subsequent drops in fertility rates.

As of 2015, 22 of the 25 oldest countries are located in Europe, but parts of Asia such as South Korea, Hong Kong, and Taiwan are expected to be in the list by 2050.

[109] The smaller states of Singapore and Taiwan are also struggling to boost fertility rates from record lows and manage aging populations.

[110] More than a third of the world's elderly (65 and older) live in East Asia and the Pacific, and many of the economic concerns raised first in Japan can be projected to the rest of the region.