Red panda

It is not closely related to the giant panda, which is a bear, though both possess elongated wrist bones or "false thumbs" used for grasping bamboo.

The evolutionary lineage of the red panda (Ailuridae) stretches back around 25 to 18 million years ago, as indicated by extinct fossil relatives found in Eurasia and North America.

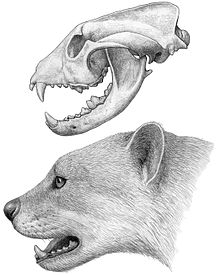

Cuvier's description was based on zoological specimens, including skin, paws, jawbones and teeth "from the mountains north of India", as well as an account by Alfred Duvaucel.

The Chinese subspecies has a more curved forehead and sloping snout, a darker coat with a less white face and more contrast between the tail rings.

[19] The puma-sized Simocyon was likely a tree-climber and shared a "false thumb"—an extended wrist bone—with the modern species, suggesting the appendage was an adaptation to arboreal locomotion and not to feed on bamboo.

The modern red panda's lineage became adapted for a specialised bamboo diet, having molar-like premolars and more elevated cusps.

Researchers have compared it to the genome of the giant panda to learn the genetics of convergent evolution, as both species have false thumbs and are adapted for a specialised bamboo diet despite having the digestive system of a carnivore.

The muzzle, cheeks, brows and inner ear margins are mostly white while the bushy tail has red and buff ring patterns and a dark brown tip.

[28] The red panda has a relatively small head, though proportionally larger than in similarly sized raccoons, with a reduced snout and triangular ears, and nearly evenly lengthed limbs.

The digestive system of the red panda is only 4.2 times its body length, with a simple stomach, no noticeable divide between the ileum and colon, and no caecum.

[28] Both sexes have paired anal glands that emit a secretion consisting of long-chain fatty acids, cholesterol, squalene and 2-Piperidinone; the latter is the most odoriferous compound and is perceived by humans as having an ammoniacal or pepper-like odour.

[33] The red panda inhabits Nepal, the states of Sikkim, West Bengal and Arunachal Pradesh in India, Bhutan, southern Tibet, northern Myanmar and China's Sichuan and Yunnan provinces.

[40] Panchthar and Ilam Districts represent its easternmost range in the country, where its habitat in forest patches is surrounded by villages, livestock pastures and roads.

[35][43][44][45] Records in Bhutan, Arunachal Pradesh's Pangchen Valley, West Kameng and Shi Yomi districts indicate that it frequents habitats with Yushania and Thamnocalamus bamboo, medium-sized Rhododendron, whitebeam and chinquapin trees.

In Fengtongzhai and Yele National Nature Reserves, red panda microhabitat is characterised by steep slopes with lots of bamboo stems, shrubs, fallen logs and stumps, whereas the giant panda prefers gentler slopes with taller but lesser amounts of bamboo and less habitat features overall.

It typically rests or sleeps in trees or other elevated spaces, stretched out prone on a branch with legs dangling when it is hot, and curled up with its hindlimb over the face when it is cold.

[43] In Bhutan's Jigme Dorji National Park, red panda faeces found in the fruiting season contained seeds of Himalayan ivy.

[70] At least seven different vocalisations have been recorded from the red panda, comprising growls, barks, squeals, hoots, bleats, grunts and twitters.

[73] Prior to giving birth, the female selects a denning site, such as a tree, log or stump hollow or rock crevice, and builds a nest using material from nearby, such as twigs, sticks, branches, bark bits, leaves, grass and moss.

[29] Two radio-collared cubs in eastern Nepal separated from their mothers at the age of 7–8 months and left their birth areas three weeks later.

[74] Faecal samples of red panda collected in Nepal contained parasitic protozoa, amoebozoans, roundworms, trematodes and tapeworms.

[75][76] Roundworms, tapeworms and coccidia were also found in red panda scat collected in Rara and Langtang National Parks.

[82] The red panda is primarily threatened by the destruction and fragmentation of its habitat, the causes of which include increasing human population, deforestation, the unlawful taking of non-wood forest material and disturbances by herders and livestock.

[83] The cut lumber stock in Sichuan alone reached 2,661,000 m3 (94,000,000 cu ft) in 1958–1960, and around 3,597.9 km2 (1,389.2 sq mi) of red panda habitat were logged between the mid-1970s and late 1990s.

[48] Throughout Nepal, the red panda habitat outside protected areas is negatively affected by solid waste, livestock trails and herding stations, and people collecting firewood and medicinal plants.

[43][84] Threats identified in Nepal's Lamjung District include grazing by livestock during seasonal transhumance, human-made forest fires and the collection of bamboo as cattle fodder in winter.

[39] In southwestern China, the red panda is hunted for its fur, especially for the highly valued bushy tails, from which hats are produced.

[92] Since 2010, community-based conservation programmes have been initiated in 10 districts in Nepal that aim to help villagers reduce their dependence on natural resources through improved herding and food processing practices and alternative income possibilities.

[93] From 2016 to 2019, 35 ha (86 acres) of high-elevation rangeland in Merak, Bhutan, was restored and fenced in cooperation with 120 herder families to protect the red panda forest habitat and improve communal land.

[94] Villagers in Arunachal Pradesh established two community conservation areas to protect the red panda habitat from disturbance and exploitation of forest resources.