Wonder Stories

It was founded by Hugo Gernsback in 1929 after he had lost control of his first science fiction magazine, Amazing Stories, when his media company Experimenter Publishing went bankrupt.

For a period in the early 1940s it was aimed at younger readers, with a juvenile editorial tone and covers that depicted beautiful women in implausibly revealing spacesuits.

By the end of the 19th century, stories centered on scientific inventions and set in the future, in the tradition of Jules Verne, were appearing regularly in popular fiction magazines.

He repeatedly made this assertion in Amazing Stories, and continued to do so in his editorials for the new magazines, stating, for example, that "teachers encourage the reading of this fiction because they know that it gives the pupil a fundamental knowledge of science and aviation.

Science fiction historian Everett Bleiler describes this as "fakery, pure and simple", asserting that there is no evidence that the men on the panel—some of whom, such as Lee De Forest, were well-known scientists—had any editorial influence.

[28] The schedule stuttered for the first time, missing the July and September 1933 issues;[28] the recent bankruptcy of the company's distributor, Eastern Distributing Corporation, may have been partly responsible for this disruption.

To bypass the dealers, he made a plea in the March 1936 issue to his readers, asking them to subscribe, and proposing to distribute Wonder Stories solely by subscription.

[14] In February 1938 Weisinger asked for reader feedback regarding the idea of a companion magazine; the response was positive, and in January 1939 the first issue of Startling Stories appeared, alternating months with Thrilling Wonder.

Friend, a pulp writer with more experience in Westerns than science fiction, though he had published a novel, The Kid from Mars, in Startling Stories just the year before.

These included: When Air Wonder Stories was launched in the middle of 1929 there were already pulp magazines such as Sky Birds and Flying Aces which focused on aerial adventures.

[58] By contrast, Gernsback said he planned to fill Air Wonder solely with "flying stories of the future, strictly along scientific-mechanical-technical lines, full of adventure, exploration and achievement.

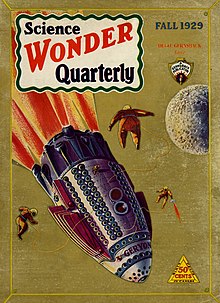

[60] Science Wonder's first issue included the first part of a serial, The Reign of the Ray, by Fletcher Pratt and Irwin Lester, and short stories by Stanton Coblentz and David H. Keller.

Writers who first appeared in the pages of these magazines include Neil R. Jones, Ed Earl Repp, Raymond Z. Gallun and Lloyd Eshbach.

On 11 May 1931 he wrote to his regular contributors to tell them that their science fiction stories "should deal realistically with the effect upon people, individually and in groups, of a scientific invention or discovery. ...

In other words, allow yourself one fundamental assumption—that a certain machine or discovery is possible—and then show what would be its logical and dramatic consequences upon the world; also what would be the effect upon the group of characters that you pick to carry your theme.

[63] Some of his correspondence has survived, including an exchange with Jack Williamson, whom Lasser commissioned in early 1932 to write a story based on a plot provided by a reader—the winning entry in one of the magazine's competitions.

Science fiction historian Sam Moskowitz has suggested that the reason was the poor financial state of Wonder Stories—Gernsback perhaps avoided corresponding with authors as he owed many of them money.

[65][66] Lasser allowed the letter column to become a free discussion of ideas and values, and published stories dealing with topics such as the relationship between the sexes.

Gernsback published two issues of Technocracy Review, which Lasser edited, commissioning stories based on technocratic ideas from Nat Schachner.

Despite these handicaps, Hornig managed to find some good material, including Stanley G. Weinbaum's "A Martian Odyssey", which appeared in the July 1934 Wonder and has been frequently reprinted.

[22] Both Lasser and Hornig printed fiction translated from French and German writers, including Otfrid von Hanstein and Otto Willi Gail.

With the rise of Adolf Hitler in Germany in the 1930s a few readers (including Donald Wollheim) wrote letters complaining about the inclusion of German stories.

Several well-known writers contributed, including Ray Cummings, and John W. Campbell, whose "Brain-Stealers of Mars" series began in Thrilling Wonder in the December 1936 issue.

He used the alias "Sergeant Saturn" and was generally condescending to the readers; this may not have been his fault as Margulies, who was still the editorial director, probably wanted him to attract a younger readership.

Under Friend's direction, Earle K. Bergey transformed the look of Thrilling Wonder Stories by foregrounding human figures in space, focusing on the anatomy of women in implausibly revealing spacesuits and his trademark "brass brassières".

[45][80] He argued against restrictions in science fiction themes, and in 1952 published Philip José Farmer's "The Lovers", a ground-breaking story about inter-species sex, in Startling.

The magazine was less constrained by pulp convention than its competitors, and published some novels such as Eric Temple Bell's The Time Stream and Festus Pragnell's The Green Man of Graypec, which were not in the mainstream of development of the science fiction genre.

Until the mid-1940s it was focused on younger readers, and by the time Merwin and Mines introduced a more adult approach, Astounding Science Fiction had taken over as the unquestioned leader of the field.

More details are given in the publishing history section, above, which focuses on when the editors involved actually obtained control of the magazine contents, instead of when their names appeared on the masthead.

The short duration of these price cuts suggests Gernsback rapidly realized that the additional circulation they gained him cost too much in lost revenue.