Air raids on Japan

During that year the naval attaché to the Embassy of the United States in Tokyo reported that Japan's civil defenses were weak, and proposals were made for American aircrew to volunteer for service with Chinese forces in the Second Sino-Japanese War.

These aircraft reached India, but remained there as the Japanese conquest of Burma caused logistics problems and Chinese Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek was reluctant to allow them to operate from territory under his control.

[12] In July 1942, the commander of the American Volunteer Group, Colonel Claire Lee Chennault, sought a force of 100 P-47 Thunderbolt fighters and 30 B-25 Mitchell medium bombers, which he believed would be sufficient to "destroy" the Japanese aircraft industry.

The Japanese military later incorrectly concluded that the ROCAF had aircraft capable of mounting attacks at a range of 1,300 miles (2,100 km) from their bases, and took precautions against potential raids on western Japan when Chinese forces launched an offensive during 1939.

In an operation conducted primarily to raise morale in the United States and to avenge the attack on Pearl Harbor, 16 B-25 Mitchell medium bombers were carried from San Francisco to within range of Japan on the aircraft carrier USS Hornet.

[33] In late 1943, the United States Joint Chiefs of Staff approved a proposal to begin the strategic air campaign against the Japanese home islands and East Asia by basing B-29 Superfortress heavy bombers in India and establishing forward airfields in China.

This strategy, designated Operation Matterhorn, involved the construction of large airstrips near Chengdu in inland China which would be used to refuel B-29s traveling from bases in Bengal en route to targets in Japan.

[45][47][48] Despite these improvements, Japan's air defenses remained inadequate as few aircraft and anti-aircraft guns could effectively engage B-29s at their cruising altitude of 30,000 feet (9,100 m) and the number of radar stations capable of providing early warning of raids was insufficient.

Moreover, the diversion of some supply aircraft flown between India and China to support XX Bomber Command's efforts may have prevented the Fourteenth Air Force from undertaking more effective operations against Japanese positions and shipping.

The official history of the USAAF judged that the difficulty of transporting adequate supplies to India and China was the most important factor behind the failure of Operation Matterhorn, though technical problems with the B-29s and the inexperience of their crews also hindered the campaign.

[63] The adverse weather conditions common over Japan also limited the effectiveness of the Superfortresses, as crews that managed to reach their target were often unable to bomb accurately due to high winds or cloud cover.

[68] These bases were more capable of supporting an intensive air campaign against Japan than those in China as they could be easily supplied by sea and were 1,500 miles (2,400 km) south of Tokyo, which allowed B-29s to strike most areas in the home islands and return without refueling.

[73] In response, the IJAAF and IJN stepped up their air attacks on B-29 bases in the Mariana Islands from 27 November; these raids continued until January 1945 and resulted in the destruction of 11 Superfortresses and damage to another 43 for the loss of probably 37 Japanese aircraft.

Hansell protested this order, as he believed that precision attacks were starting to produce results and moving to area bombardment would be counterproductive, but agreed to the operation after he was assured that it did not represent a general shift in tactics.

[87] From 19 February to 3 March, XXI Bomber Command conducted a series of precision bombing raids on aircraft factories that sought to tie down Japanese air units so they could not participate in the Battle of Iwo Jima.

Japan's main industrial facilities were vulnerable to such attacks as they were concentrated in several large cities and a high proportion of production took place in homes and small factories in urban areas.

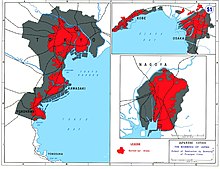

The planners estimated that incendiary bomb attacks on Japan's six largest cities could cause physical damage to almost 40 percent of industrial facilities and result in the loss of 7.6 million man-months of labor.

[98] In light of the poor results of the precision bombing campaign and the success of the 25 February raid on Tokyo, and considering that many tons of incendiaries were now available to him, LeMay decided to begin firebombing attacks on Japan's main cities during early March 1945.

[101] The decision to use firebombing tactics represented a move away from the USAAF's previous focus on precision bombing, and was believed by senior officials in the military and US Government to be justified by the need to rapidly bring the war to an end.

[124][125][126] LeMay resumed night firebombing raids on 13 April when 327 B-29s attacked the arsenal district of Tokyo and destroyed 11.4 square miles (30 km2) of the city, including several armaments factories.

This decision was made despite a recommendation from the United States Strategic Bombing Survey (USSBS) team, which was assessing the effectiveness of air attacks on Germany, that operations against Japan should focus on the country's transportation network and other targets with the goal of crippling the movement of goods and destroying food supplies.

The Commonwealth Tiger Force, which was to include Australian, British, Canadian and New Zealand heavy bomber squadrons and attack Japan from Okinawa, was also to come under the command of USASTAF when it arrived in the region during late 1945.

[190][191] Strikes on the Tokyo area on 17 July were disrupted by bad weather, but the next day aircraft from the fleet attacked Yokosuka naval base where they damaged the battleship Nagato and sank four other warships.

[196] Its next attacks against Japan took place on 9 and 10 August, These were directed at a buildup of Japanese aircraft in northern Honshu which Allied intelligence believed were to be used to conduct a commando raid against the B-29 bases in the Marianas.

[255] Eight bombs were scheduled to have been completed by November, and General George Marshall, the Chief of Staff of the United States Army, was advocating that they be reserved for use against tactical targets in support of the planned invasion rather than be dropped on cities.

In fact, 828 B-29s escorted by 186 fighters (for a total of 1,014 aircraft) were dispatched; during the day precision raids were made against targets at Iwakuni, Osaka and Tokoyama and at night the cities of Kumagaya and Isesaki were firebombed.

[261][262] While the Eighth Air Force units at Okinawa had not yet conducted any missions against Japan, General Doolittle decided not to contribute aircraft to this operation as he did not want to risk the lives of the men under his command when the war was effectively over.

[269] While Spaatz ordered that B-29s and fighters fly continuous show of force patrols of the Tokyo area from 19 August until the formal surrender ceremony took place, these operations were initially frustrated by bad weather and logistics problems.

[277] In September 1945 the Japanese government offered to provide material for 300,000 small temporary houses to evacuees, but the emphasis of its policies in this year and 1946 was to stop people returning to the damaged cities.

[311] Mark Selden described the summer 1945 peak of the bombing campaign as "still perhaps unrivaled in the magnitude of human slaughter" and stated that the factors contributing to its intensity were a combination of "technological breakthroughs, American nationalism, and the erosion of moral and political scruples about killing of civilians, perhaps intensified by the racism that crystallized in the Pacific theater".