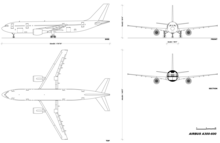

Airbus A300

In September 1967, aircraft manufacturers in France, West Germany and the United Kingdom signed an initial memorandum of understanding to collaborate to develop an innovative large airliner.

While studies were performed and considered, such as a stretched twin-engine variant of the Hawker Siddeley Trident and an expanded development of the British Aircraft Corporation (BAC) One-Eleven, designated the BAC Two-Eleven, it was recognized that if each of the European manufacturers were to launch similar aircraft into the market at the same time, neither would achieve sales volume needed to make them viable.

[2][6]: 37–38 National governments were also keen to support such efforts amid a belief that American manufacturers could dominate the European Economic Community;[7] in particular, Germany had ambitions for a multinational airliner project to invigorate its aircraft industry, which had declined considerably following the Second World War.

[3][8] In July 1967, during a high-profile meeting between French, German, and British ministers, an agreement was made for greater cooperation between European nations in the field of aviation technology, and "for the joint development and production of an airbus".

[2][9]: 34 The word airbus at this point was a generic aviation term for a larger commercial aircraft, and was considered acceptable in multiple languages, including French.

[2][6]: 38 An early design goal for the A300 that Béteille had stressed the importance of was the incorporation of a high level of technology, which would serve as a decisive advantage over prospective competitors.

For this reason, the A300 would feature the first use of composite materials of any passenger aircraft, the leading and trailing edges of the tail fin being composed of glass fibre reinforced plastic.

[10] These decisions were partially influenced by feedback from various airlines, such as Air France and Lufthansa, as an emphasis had been placed on determining the specifics of what kind of aircraft that potential operators were seeking.

[14] In December 1968, the French and British partner companies (Sud Aviation and Hawker Siddeley) proposed a revised configuration, the 250-seat Airbus A250.

[10][16]: 16 For increased flexibility, the cabin floor was raised so that standard LD3 freight containers could be accommodated side-by-side, allowing more cargo to be carried.

[15] Additionally, the managing director of Hawker Siddeley, Sir Arnold Alexander Hall, decided that his company would remain in the project as a favoured sub-contractor, developing and manufacturing the wings for the A300, which would prove to be an important contributor to the performance of subsequent versions.

[2] The intention of the project was to produce an aircraft that was smaller, lighter, and more economical than its three-engine American rivals, the McDonnell Douglas DC-10 and the Lockheed L-1011 TriStar.

[10] In order to meet Air France's demands for an aircraft larger than 250-seat A300B, it was decided to stretch the fuselage to create a new variant, designated as the A300B2, which would be offered alongside the original 250-seat A300B, henceforth referred to as the A300B1.

[6]: 39 [10][16]: 21 In the aftermath of the Paris Air Show agreement, it was decided that, in order to provide effective management of responsibilities, a Groupement d'intérêt économique would be established, allowing the various partners to work together on the project while remaining separate business entities.

The combined use of ferries and roads were used for the assembly of the first A300, however this was time-consuming and not viewed as ideal by Felix Kracht, Airbus Industrie's production director.

[10] Kracht's solution was to have the various A300 sections brought to Toulouse by a fleet of Boeing 377-derived Aero Spacelines Super Guppy aircraft, by which means none of the manufacturing sites were more than two hours away.

[8] Initially, the success of the consortium was poor, in part due to the economic consequences of the 1973 oil crisis,[6]: 40 [8][9]: 34 but by 1979 there were 81 A300 passenger liners in service with 14 airlines, alongside 133 firm orders and 88 options.

[6]: 40 Another world-first of the A300 is the use of composite materials on a commercial aircraft, which were used on both secondary and later primary airframe structures, decreasing overall weight and improving cost-effectiveness.

[12]: 57 The lack of a third tail-mounted engine, as per the trijet configuration used by some competing airliners, allowed for the wings to be located further forwards and to reduce the size of the vertical stabiliser and elevator, which had the effect of increasing the aircraft's flight performance and fuel efficiency.

[19][21] Additional composites were also made use of, such as carbon-fibre-reinforced polymer (CFRP), as well as their presence in an increasing proportion of the aircraft's components, including the spoilers, rudder, air brakes, and landing gear doors.

[20] Various variants of the A300 were built to meet customer demands, often for diverse roles such as aerial refueling tankers, freighter models (new-build and conversions), combi aircraft, military airlifter, and VIP transport.

Perhaps the most visually unique of the variants is the A300-600ST Beluga, an oversized cargo-carrying model operated by Airbus to carry aircraft sections between their manufacturing facilities.

The saviour of the A300 was the advent of ETOPS, a revised FAA rule which allows twin-engine jets to fly long-distance routes that were previously off-limits to them.

The A300 would replacing the aging DC-9s and 727-100s but in smaller numbers, while being a twinjet sized between the Tristars and 727-200s, and capable of operating from short runway airports with sufficient range from New York City to Miami.

[6]: 40 [8][18] Aviation author John Bowen alleged that various concessions, such as loan guarantees from European governments and compensation payments, were a factor in the decision as well.

Although the A300 was originally too large for Eastern's exiting routes, Airbus provided a fixed subsidy for a 57% load factor which decreased for every percent above that figure.

The CF6-50A powered A300B2-100 was 2.6 m (8.5 ft) longer than the A300B1 and had an increased MTOW of 137 t (302,000 lb), allowing for 30 additional seats and bringing the typical passenger count up to 281, with capacity for 20 LD3 containers.

[42]: 52, 53 [43] The variant had an increased MTOW of 142 t (313,000 lb) and was powered by CF6-50C engines, was certified on 23 June 1976, and entered service with South African Airways in November 1976.

Introduced by Garuda Indonesian Airways in 1982 The A300-600, officially designated as the A300B4-600, was slightly longer than the A300B2 and A300B4 variants and had an increased interior space from using a similar rear fuselage to the Airbus A310, this allowed it to have two additional rows of seats.

[42]: 82 Other changes include an improved wing featuring a recambered trailing edge, the incorporation of simpler single-slotted Fowler flaps, the deletion of slat fences, and the removal of the outboard ailerons after they were deemed unnecessary on the A310.