Air mass (astronomy)

Tables of air mass have been published by numerous authors, including Bemporad (1904), Allen (1973),[1] and Kasten & Young (1989).

In the corresponding simplified relative air mass, the average density cancels out in the fraction, leading to the ratio of path lengths:

[2] When the zenith angle is small to moderate, a good approximation is given by assuming a homogeneous plane-parallel atmosphere (i.e., one in which density is constant and Earth's curvature is ignored).

However, because the Earth is not flat, this formula is only usable for zenith angles up to about 60° to 75°, depending on accuracy requirements.

Many formulas have been developed to fit tabular values of air mass; one by Young & Irvine (1967) included a simple corrective term:

This gives usable results up to approximately 80°, but the accuracy degrades rapidly at greater zenith angles.

The calculated air mass reaches a maximum of 11.13 at 86.6°, becomes zero at 88°, and approaches negative infinity at the horizon.

The plot of this formula on the accompanying graph includes a correction for atmospheric refraction so that the calculated air mass is for apparent rather than true zenith angle.

As with the previous formula, the calculated air mass reaches a maximum, and then approaches negative infinity at the horizon.

which gives reasonable results for high zenith angles, with a horizon air mass of 40.

which gives reasonable results for zenith angles of up to 90°, with an air mass of approximately 38 at the horizon.

[4] Interpolative formulas attempt to provide a good fit to tabular values of air mass using minimal computational overhead.

If atmospheric refraction is ignored, it can be shown from simple geometrical considerations (Schoenberg 1929, 173) that the path

The homogeneous spherical model slightly underestimates the rate of increase in air mass near the horizon; a reasonable overall fit to values determined from more rigorous models can be had by setting the air mass to match a value at a zenith angle less than 90°.

The model is usable (i.e., it does not diverge or go to zero) at all zenith angles, including those greater than 90° (see § Homogeneous spherical atmosphere with elevated observer).

[5] However, for zenith angles less than 90°, a better fit to accepted values of air mass can be had with several of the interpolative formulas.

In a real atmosphere, density is not constant (it decreases with elevation above mean sea level.

The absolute air mass for the geometrical light path discussed above, becomes, for a sea-level observer,

Using a scale height of 8435 m, Earth's mean radius of 6371 km, and including the correction for refraction,

[6] When atmospheric refraction is considered, ray tracing becomes necessary (Kivalov 2007), and the absolute air mass integral becomes[7]

expanding the left- and right-hand sides, eliminating the common terms, and rearranging gives

The relative contribution of each source varies with elevation above sea level, and the concentrations of aerosols and ozone cannot be derived simply from hydrostatic considerations.

Rigorously, when the extinction coefficient depends on elevation, it must be determined as part of the air mass integral, as described by Thomason, Herman & Reagan (1983).

In optical astronomy, the air mass provides an indication of the deterioration of the observed image, not only as regards direct effects of spectral absorption, scattering and reduced brightness, but also an aggregation of visual aberrations, e.g. resulting from atmospheric turbulence, collectively referred to as the quality of the "seeing".

The Greenwood frequency and Fried parameter, both relevant for adaptive optics, depend on the air mass above them (or more specifically, on the zenith angle).

In radio astronomy the air mass (which influences the optical path length) is not relevant.

Newer aperture synthesis radio telescopes are especially affected by this as they “see” a much larger portion of the sky and thus the ionosphere.

In fact, LOFAR needs to explicitly calibrate for these distorting effects (van der Tol & van der Veen 2007; de Vos, Gunst & Nijboer 2009), but on the other hand can also study the ionosphere by instead measuring these distortions (Thidé 2007).

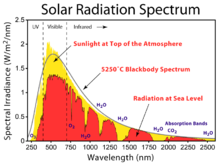

Photovoltaic modules are commonly rated using spectral irradiance for an air mass of 1.5 (AM1.5); tables of these standard spectra are given in ASTM G 173-03.

[9] For many solar energy applications when high accuracy near the horizon is not required, air mass is commonly determined using the simple secant formula described in § Plane-parallel atmosphere.