Radio astronomy

The first detection of radio waves from an astronomical object was in 1933, when Karl Jansky at Bell Telephone Laboratories reported radiation coming from the Milky Way.

The discovery of the cosmic microwave background radiation, regarded as evidence for the Big Bang theory, was made through radio astronomy.

Several attempts were made to detect radio emission from the Sun including an experiment by German astrophysicists Johannes Wilsing and Julius Scheiner in 1896 and a centimeter wave radiation apparatus set up by Oliver Lodge between 1897 and 1900.

As a newly hired radio engineer with Bell Telephone Laboratories, he was assigned the task to investigate static that might interfere with short wave transatlantic voice transmissions.

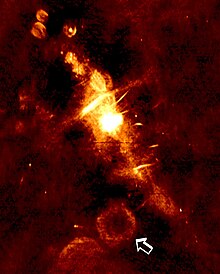

[2] By comparing his observations with optical astronomical maps, Jansky eventually concluded that the radiation source peaked when his antenna was aimed at the densest part of the Milky Way in the constellation of Sagittarius.

[4] In October 1933, his discovery was published in a journal article entitled "Electrical disturbances apparently of extraterrestrial origin" in the Proceedings of the Institute of Radio Engineers.

"[2][6] (Jansky's peak radio source, one of the brightest in the sky, was designated Sagittarius A in the 1950s and was later hypothesized to be emitted by electrons in a strong magnetic field.

)[7][8][9][10] After 1935, Jansky wanted to investigate the radio waves from the Milky Way in further detail, but Bell Labs reassigned him to another project, so he did no further work in the field of astronomy.

His pioneering efforts in the field of radio astronomy have been recognized by the naming of the fundamental unit of flux density, the jansky (Jy), after him.

[12] On February 27, 1942, James Stanley Hey, a British Army research officer, made the first detection of radio waves emitted by the Sun.

[15] Several other people independently discovered solar radio waves, including E. Schott in Denmark[16] and Elizabeth Alexander working on Norfolk Island.

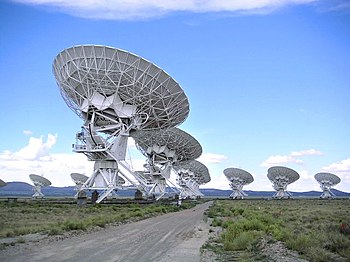

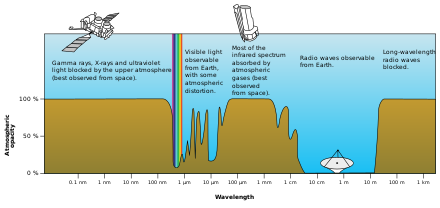

Also since angular resolution is a function of the diameter of the "objective" in proportion to the wavelength of the electromagnetic radiation being observed, radio telescopes have to be much larger in comparison to their optical counterparts.

For example, a 1-meter diameter optical telescope is two million times bigger than the wavelength of light observed giving it a resolution of roughly 0.3 arc seconds, whereas a radio telescope "dish" many times that size may, depending on the wavelength observed, only be able to resolve an object the size of the full moon (30 minutes of arc).

The first use of a radio interferometer for an astronomical observation was carried out by Payne-Scott, Pawsey and Lindsay McCready on 26 January 1946 using a single converted radar antenna (broadside array) at 200 MHz near Sydney, Australia.

The use of a sea-cliff interferometer had been demonstrated by numerous groups in Australia, Iran and the UK during World War II, who had observed interference fringes (the direct radar return radiation and the reflected signal from the sea) from incoming aircraft.

They showed that the radio radiation was smaller than 10 arc minutes in size and also detected circular polarization in the Type I bursts.

Two other groups had also detected circular polarization at about the same time (David Martyn in Australia and Edward Appleton with James Stanley Hey in the UK).

However, radio telescopes have also been used to investigate objects much closer to home, including observations of the Sun and solar activity, and radar mapping of the planets.