Ajanta Caves

[8][9] The caves also present paintings depicting the past lives [10] and rebirths of the Buddha, pictorial tales from Aryasura's Jatakamala, and rock-cut sculptures of Buddhist deities.

[46] Some of the Hūṇas, the Alchon Huns of Toramana, were precisely ruling the neighbouring area of Malwa, at the doorstep of the Western Deccan, at the time the Ajanta caves were made.

[53] The Nizam's Director of Archaeology obtained the services of two experts from Italy, Professor Lorenzo Cecconi, assisted by Count Orsini, to restore the paintings in the caves.

[54] The Director of Archaeology for the last Nizam of Hyderabad said of the work of Cecconi and Orsini: The repairs to the caves and the cleaning and conservation of the frescoes have been carried out on such sound principles and in such a scientific manner that these matchless monuments have found a fresh lease of life for at least a couple of centuries.

[57] The caves are carved out of flood basalt and granite rock of a cliff, part of the Deccan Traps formed by successive volcanic eruptions at the end of the Cretaceous geological period.

[60] A grand gateway to the site was carved, at the apex of the gorge's horseshoe between caves 15 and 16, as approached from the river, and it is decorated with elephants on either side and a nāga, or protective Naga (snake) deity.

They are luxurious, sensuous and celebrate physical beauty, aspects that early Western observers felt were shockingly out of place in these caves presumed to be meant for religious worship and ascetic monastic life.

Unlike much Indian mural painting, compositions are not laid out in horizontal bands like a frieze, but show large scenes spreading in all directions from a single figure or group at the centre.

[96] Walter Spink has over recent decades developed a very precise and circumstantial chronology for the second period of work on the site, which unlike earlier scholars, he places entirely in the 5th century.

[32] According to Spink, Harisena encouraged a group of associates, including his prime minister Varahadeva and Upendragupta, the sub-king in whose territory Ajanta was, to dig out new caves, which were individually commissioned, some containing inscriptions recording the donation.

In the years 478–480 CE major excavation by important patrons was replaced by a rash of "intrusions" – statues added to existing caves, and small shrines dotted about where there was space between them.

A terracotta plaque of Mahishasuramardini, also known as Durga, was also found in a burnt-brick vihara monastery facing the caves on the right bank of the river Waghora that has been recently excavated.

Spink states that the Vākāṭaka Emperor Harishena was the benefactor of the work, and this is reflected in the emphasis on imagery of royalty in the cave, with those Jataka tales being selected that tell of those previous lives of the Buddha in which he was royal.

There was originally a columned portico in front of the present facade, which can be seen "half-intact in the 1880s" in pictures of the site, but this fell down completely and the remains, despite containing fine carvings, were carelessly thrown down the slope into the river and lost.

The two most famous individual painted images at Ajanta are the two over-lifesize figures of the protective bodhisattvas Padmapani and Vajrapani on either side of the entrance to the Buddha shrine on the wall of the rear aisle (see illustrations above).

[73][141] The upper storey was not envisioned in the beginning, it was added as an afterthought, likely around the time when the architects and artists abandoned further work on the geologically flawed rock of Cave 5 immediately next to it.

Other frescos depict the conversion of Nanda, miracle of Sravasti, Sujata's offering, Asita's visit, the dream of Maya, the Trapusha and Bhallika story, and the ploughing festival.

[202] The grand scale of the carving also introduced errors of taking out too much rock to shape the walls, states Spink, which led to the cave being splayed out toward the rear.

[234] It is significant in having one of the most complex capitals on a pillar at the Ajanta site, an indication of how the artists excelled and continuously improved their sophistication as they worked with the rock inside the cave.

[235] The artists carved fourteen complex miniature figures on the central panel of the right center porch pillar, while working in dim light in a cramped cave space.

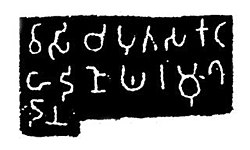

[238][239] The inscription includes a vision statement and the aim to make "a memorial on the mountain that will endure for as long as the moon and the sun continue", translates Walter Spink.

In 1846 for example, Major Robert Gill, an Army officer from Madras Presidency and a painter, was appointed by the Royal Asiatic Society to make copies of the frescos on the cave walls.

[citation needed] Another attempt was made in 1872 when the Bombay Presidency commissioned John Griffiths to work with his students to make copies of Ajanta paintings, again for shipping to England.

[268][269] The dress, the jewellery, the gender relations, the social activities depicted show at least the lifestyle of the royalty and elite,[270] and in others definitely the costumes of the common man, monks and rishi.

Ajanta caves contributes to visual and descriptive sense of the ancient and early medieval Indian culture and artistic traditions, particularly those around the Gupta Empire era period.

[280] According to Walter Spink – one of the most respected Art historians on Ajanta, these caves were by 475 CE a much-revered site to the Indians, with throngs of "travelers, pilgrims, monks and traders".

According to Indian historian Haroon Khan Sherwani: "The paintings at Ajanta clearly demonstrate the cosmopolitan character of Buddhism, which opened its way to men of all races, Greek, Persian, Saka, Pahlava, Kushan and Huna".

[284] According to Spink, James Fergusson, a 19th-century architectural historian, had decided that this scene corresponded to the Persian ambassador in 625 CE to the court of the Hindu Chalukya king Pulakeshin II.

[284][287] These assumptions by colonial British era art historians, state Spink and other scholars, has been responsible for wrongly dating this painting to the 7th century, when in fact this reflects an incomplete Harisena-era painting of a Jataka tale (the Mahasudarsana jataka, in which the enthroned king is actually the Buddha in one of his previous lives as King) with the representation of trade between India and distant lands such as Sassanian near East that was common by the 5th century.

[290] Additional evidence of international trade includes the use of the blue lapis lazuli pigment to depict foreigners in the Ajanta paintings, which must have been imported from Afghanistan or Iran.