Akhenaten

[14][25][26][27][28] Public and scholarly fascination with Akhenaten comes from his connection with Tutankhamun, the unique style and high quality of the pictorial arts he patronized, and the religion he attempted to establish, foreshadowing monotheism.

Aldred proposes that Akhenaten's unusual artistic inclinations might have been formed during his time serving Ptah, the patron god of craftsmen, whose high priests were sometimes referred to as "The Greatest of the Directors of Craftsmanship".

Egyptologist Donald B. Redford believes this implied that Amenhotep IV's eventual religious policies were not conceived of before his reign, and he did not follow a pre-established plan or program.

He ordered the construction of temples or shrines to the Aten in several cities across the country, such as Bubastis, Tell el-Borg, Heliopolis, Memphis, Nekhen, Kawa, and Kerma.

It is also possible that the purpose of the ceremony was to figuratively fill Amenhotep IV with strength before his great enterprise: the introduction of the Aten cult and the founding of the new capital Akhetaten.

These letters, found at Gurob, informing the pharaoh that the royal estates in Memphis are "in good order" and the temple of Ptah is "prosperous and flourishing", are dated to regnal year five, day nineteen of the growing season's third month.

[84] The pharaoh chose a site about halfway between Thebes, the capital at the time, and Memphis, on the east bank of the Nile, where a wadi and a natural dip in the surrounding cliffs form a silhouette similar to the "horizon" hieroglyph.

In the 200 years preceding Akhenaten's reign, following the expulsion of the Hyksos from Lower Egypt at the end of the Second Intermediate Period, the kingdom's influence and military might increased greatly.

Egypt's power reached new heights under Thutmose III, who ruled approximately 100 years before Akhenaten and led several successful military campaigns into Nubia and Syria.

Evidence suggests that the troubles on the northern frontier led to difficulties in Canaan, particularly in a struggle for power between Labaya of Shechem and Abdi-Heba of Jerusalem, which required the pharaoh to intervene in the area by dispatching Medjay troops northwards.

[101] What Rib-Hadda did not comprehend was that the Egyptian king would not organize and dispatch an entire army north just to preserve the political status quo of several minor city states on the fringes of Egypt's Asiatic Empire.

In his second or twelfth year,[111] Akhenaten ordered his Viceroy of Kush Tuthmose to lead a military expedition to quell a rebellion and raids on settlements on the Nile by Nubian nomadic tribes.

Either of these could be the campaign referred to on Tutankhamun's Restoration Stela: "if an army was sent to Djahy [southern Canaan and Syria] to broaden the boundaries of Egypt, no success of their cause came to pass.

"[115][116][117] John Coleman Darnell and Colleen Manassa also argued that Akhenaten fought with the Hittites for control of Kadesh, but was unsuccessful; the city was not recaptured until 60–70 years later, under Seti I.

[118] Overall, archeological evidence suggests that Akhenaten paid close attention to the affairs of Egyptian vassals in Canaan and Syria, though primarily not through letters such as those found at Amarna but through reports from government officials and agents.

[4] These years are poorly attested and only a few pieces of contemporary evidence survive; the lack of clarity makes reconstructing the latter part of the pharaoh's reign "a daunting task" and a controversial and contested topic of discussion among Egyptologists.

[127] Contemporary evidence suggests that a plague ravaged through the Middle East around this time,[128] and ambassadors and delegations arriving to Akhenaten's year twelve reception might have brought the disease to Egypt.

[130] Regardless of its origin, the epidemic might account for several deaths in the royal family that occurred in the last five years of Akhenaten's reign, including those of his daughters Meketaten, Neferneferure, and Setepenre.

[137] Egyptologist Aidan Dodson proposed that both Smenkhkare and Neferiti were Akhenaten's coregents to ensure the Amarna family's continued rule when Egypt was confronted with an epidemic.

Seti I also ordered that Akhenaten, Smenkhkare, Neferneferuaten, Tutankhamun, and Ay be excised from official lists of pharaohs to make it appear that Amenhotep III was immediately succeeded by Horemheb.

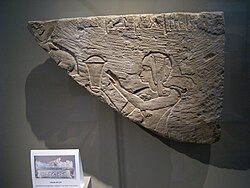

[179] The intermediate stage was marked by the elevation of the Aten above other gods and the appearance of cartouches around his inscribed name—cartouches traditionally indicating that the enclosed text is a royal name.

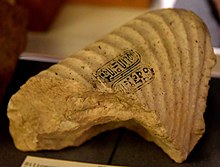

[208] Archaeological discoveries at Akhetaten show that many ordinary residents of this city chose to gouge or chisel out all references to the god Amun on even minor personal items that they owned, such as commemorative scarabs or make-up pots, perhaps for fear of being accused of having Amunist sympathies.

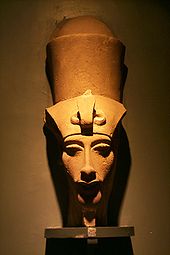

[226] Akhenaten claimed the title "The Unique One of Re", and he may have directed his artists to contrast him with the common people through a radical departure from the idealized traditional pharaoh image.

[235] Basing his arguments on his belief that the Exodus story was historical, Freud argued that Moses had been an Atenist priest who was forced to leave Egypt with his followers after Akhenaten's death.

[240][241] Freud commented on the connection between Adonai, the Egyptian Aten and the Syrian divine name of Adonis as stemming from a common root;[235] in this he was following the argument of Egyptologist Arthur Weigall.

[247] Although scholars like Brian Fagan (2015) and Robert Alter (2018) have re-opened the debate, in 1997, Redford concluded: Before much of the archaeological evidence from Thebes and from Tell el-Amarna became available, wishful thinking sometimes turned Akhenaten into a humane teacher of the true God, a mentor of Moses, a christlike figure, a philosopher before his time.

[249] Cyril Aldred,[250] following up earlier arguments of Grafton Elliot Smith[251] and James Strachey,[252] suggested that Akhenaten may have had Fröhlich's syndrome on the basis of his long jaw and his feminine appearance.

People with Marfan syndrome tend towards tallness, with a long, thin face, elongated skull, overgrown ribs, a funnel or pigeon chest, a high curved or slightly cleft palate, and larger pelvis, with enlarged thighs and spindly calves, symptoms that appear in some depictions of Akhenaten.

[261] A sexualized image of Akhenaten, building on early Western interest in the pharaoh's androgynous depictions, perceived potential homosexuality, and identification with Oedipal storytelling, also influenced modern works of art.

[268] American death metal band Nile depicted Akhenaten's judgement, punishment, and erasure from history at the hands of the pantheon that he replaced with Aten, in the song "Cast Down the Heretic", from their 2005 album Annihilation of the Wicked.