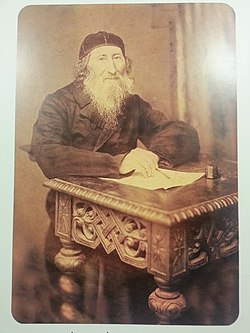

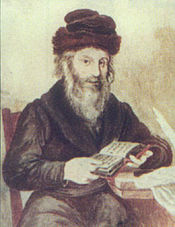

Akiva Eiger

His main public activity began when, after the efforts of his famous son-in-law, the Chatam Sofer, he was elected as the rabbi of the Polish district city of Posen, a position he held for 23 years, until his death.

His name began to spread among scholars in the area when, at just six or seven years old, he solved a difficult Talmudic sugya that had stumped the greatest minds at the Breslau yeshiva for a long time without resolution.

In this yeshiva, he met Yeshaya Pick Berlin, who later became the rabbi of Breslau and was known for his glosses on the Babylonian Talmud printed as additions to the Masoret HaShas on the pages of Vilna Shas.

Initially, Akiva Eiger was reluctant to accept a rabbinical position, preferring to be a rosh yeshiva and teach students, relying on a living stipend provided by local Jewish benefactors.

[18] In this agreement, under the title, "We have all agreed to accept the rabbi among us, to guide the people of Israel in the way they should go, and we have resolved that his meal will always come from this..." his monthly salary is detailed in the local currency (Reichstaler), including special pay for his sermons on Shabbat Shuva and Shabbat HaGadol, Kimcha D'Pischa (Passover flour), Four Cups, Etrog and Lulav, free accommodation in the rabbi's residence, notary fees for certifying marriages and inheritance agreements.

The initial salary was modest, and Akiva Eiger, who saw that it was insufficient to support his family, suspected that the community leaders assumed he had savings from the dowry he received from his wealthy father-in-law.

At his initiative, the city established the "Holy Society for Wood Distribution," a charitable fund aimed at ensuring a steady supply of firewood to heat the homes of the poor during the harsh winter.

She was my support in minimizing the Torah of the Lord within me... She watched over me to ensure my weak and fragile body was taken care of, and she shielded me from financial worries so as not to hinder me from serving God, as I now realize, unfortunately, in my many sins... My pain is as vast as the sea, my wound is severe, and darkness has fallen upon my world.

Sofer, who had recently been widowed from his first wife, forwarded the letter to his close associate, Daniel Proshtitz, who then wrote to Akiva Eiger, suggesting he match his daughter with the rabbi of Pressburg.

The process of secularization that followed the "Age of Enlightenment" was felt more strongly in smaller towns, and the 51-year-old Akiva Eiger began to question his influence over the local Jewish community, particularly the youth.

Twenty-two community members lodged a complaint with the local governor, Zbroni di Sposeti, arguing that Posen needed only a preacher who would focus on ethics and moral rectification.

At the beginning of the month of Shevat 5575 (1815), several Jews of Markisch-Friedland approached Akiva Eiger on the matter, and he replied:[40] I do not wish to leave here for the sake of money or honor, for I lack neither.

Ultimately, in a meeting attended by all parties and mediated by Yaakov Lorberbaum of Lissa, who came as an agreed-upon arbitrator, even those who had initially opposed Akiva Eiger's appointment agreed to it.

During his twenty-three years in Posen, he maintained a strict and fixed daily schedule: he woke up at 4:00 AM, studied Mishnah until 6:00 AM, and then delivered a one-hour lesson to a group of laymen at the synagogue before the morning prayer, which he allotted an hour for.

[50] At 4:00 PM, he prayed Mincha (afternoon prayer), which he set at this relatively early time to maintain a consistent schedule even during the winter, when sunset occurs earlier.

[51] That Rabbi Akiva Eger was a seasoned activist in communal matters, sowing righteousness, avoiding honor, and truly despising the rabbinate in its most literal and plain sense—this we do not know from his responsa, nor from his "Talmud Margins," but from what is told about him among the people.

He ensured that the committee funded cleaning services for the homes of the poor and distributed proclamations in the name of religion about the obligation to safeguard health by boiling drinking water and maintaining personal cleanliness.

As the High Holy Days approached that year, he decreed that a lottery be held to determine which community members would pray in the synagogue during the Rosh Hashanah prayers and which during Yom Kippur, thus reducing the number of attendees to one-third.

[54] The negotiations ceased when, in March 1823, the district head, possibly following a denunciation, issued an order banning Lorberbaum's return to the city on the grounds that he was a foreign citizen.

He appointed Akiva Eiger as the sole trustee of the institutions, stating: "I rely on the rabbi's great fear of God, his Torah knowledge, and integrity, so that his will would be considered as my own."

Despite his long and positive relationship with the Lifshitz family, Akiva Eiger opposed the idea, fearing it would set a precedent, especially considering the general religious situation in Europe at the time, that could serve reform advocates seeking to appoint talented young individuals who were not yet experts in or experienced with halachic rulings.

In parallel, he wrote to the town's shochet instructing him not to bring any kashrut questions regarding animals or poultry before "the bachelor Baruch Yitzchak" and not to allow him to check the slaughtering knife or examine it under his supervision.

Upon the news of his death, the local Jewish leadership declared a "work cessation," a general order to close shops and businesses to pay last respects to such an important figure.

A rhymed passage from the poem's introduction justifies the act of eulogy, reflecting the shock and silence that struck the Jewish world upon Akiva Eiger's passing: And if His holy word binds me in chains - To lament him and weep, his humility restrains me, I have not walked in greatness, and I am a man of uncircumcised lips, And I fear lest my tongue sin to break his command - Shall I guard my mouth with restraint, heed his injunction?

In his response published in the compilation "Eleh Divrei HaBrit" against the first Reform synagogue, he argues: If we allow ourselves to annul even a single letter of the words of the Sages, then the entire Torah is at risk.

Research into these annotations has been conducted by Chaim Dov Shavel, who partially published his findings in his book "The Teachings of Akiva Eiger in the Glosses of the Talmud" in 1959 (covering parts of Seder Moed).

Yissachar Dov Heltercht from Lubranitz published his book Chazot Kashot, stating: "It is dedicated to resolving over a thousand questions raised on the Talmud by our holy Rabbi... the marvel of the generation, the pride of Israel... Akiva Eger in his work Derush and Chiddush [!]

Another ongoing attempt was made by Shmuel Aharon Shazuri, who dedicated a regular column titled "Asheshot" in his journal Kol Torah[79] systematically aimed at resolving Eiger's questions in the margins of the Talmud.

As Akiva Eiger's works are scattered across a wide range of publications, including books, journals, pamphlets, and even individual pages published in various venues, many have seen multiple editions and photographic reproductions.

These collections hold great historical and biographical significance, echoing Thomas Jefferson’s observation that “the letters of a man, especially one who frequently engaged in correspondence, serve as a true and complete life journal.” I heard from reliable sources that the holy light of the diaspora, Rabbi Akiva Eger, before being appointed as the leader of Israel, would visit the hospital called 'Spital' daily... And later, when he was elevated to being the shepherd of Israel, and due to his many duties, he could not always visit, he hired a person to go there daily and report all the details and events as they were.

A processed detail from the painting by Julius Knorr The Market Area in Posen [2]

(Głogowska Street)

Akiva Eiger's gravestone is on the bottom left row

The top of the gravestone reads: "...which is buried here or near this location"