Al Smith

The son of an Irish-American mother and a Civil War–veteran Italian-American father, true surname Ferraro, Smith was raised on the Lower East Side of Manhattan near the Brooklyn Bridge.

Smith was the foremost urban leader of the efficiency movement in the United States and was noted for achieving a wide range of reforms as the New York governor in the 1920s.

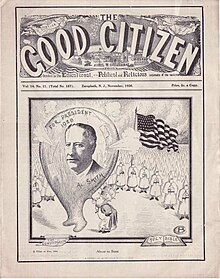

[3] Incumbent Republican Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover was aided by national prosperity, the absence of American involvement in war, and anti-Catholic bigotry, and he defeated Smith in a landslide in 1928.

Smith was born at 174 South Street and raised in the Fourth Ward on the Lower East Side of Manhattan in 1873; he resided there for his entire life.

Smith grew up with his family struggling financially in the Gilded Age; New York City matured and completed major infrastructure projects.

Although indebted to the Tammany Hall political machine (and particularly to its boss, "Silent" Charlie Murphy), he remained untarnished by corruption and worked for the passage of progressive legislation.

He staunchly supported labor unions and pressed for protective legislation for the workers, stressing the need to expand the rights of working women in particular.

A “New Era Progressive”, Smith advocated local governnment funded facilities and services such as hospitals, parks and schools in poor and working-class areas.

"[17][18] New laws mandated better building access and egress, fireproofing requirements, the availability of fire extinguishers, the installation of alarm systems and automatic sprinklers, better eating and toilet facilities for workers, and limited the number of hours that women and children could work.

[20] In 1919, Smith gave the famous speech "A man as low and mean as I can picture",[21] making a drastic break with publisher William Randolph Hearst.

Smith offered alcohol to guests at the Executive Mansion in Albany, and repealed the state's Prohibition enforcement statute, the Mullan-Gage law.

"[1] Smith represented the urban, east coast wing of the party as an anti-prohibition "wet" candidate, while his main rival for the nomination, President Woodrow Wilson's son-in-law William Gibbs McAdoo, a former Secretary of the Treasury, stood for the more rural tradition and prohibition "dry" candidacy.

[26] The Republican Party was still benefiting from an economic boom, as well as a failure to reapportion Congress and the electoral college following the 1920 census,[27] which had registered a 15 percent increase in the urban population.

Scott Farris notes that the anti-Catholicism of the American society was the sole reason behind Smith's defeat, as even contemporary Prohibition activists would admit that their main problem with the Democratic candidate was his faith and not any political view.

Bob Jones Sr., a prominent Protestant pastor in South Carolina, said:I'll tell you, brother, that the big issue we've got to face ain't the liquor question.

[29] William Allen White, a renowned newspaper editor, warned that Catholicism would erode the moral standards of America, saying that "the whole Puritan civilization which has built a sturdy, orderly nation is threatened by Smith."

[29]White rural conservatives in the South also believed that Smith's close association with Tammany Hall, the Democratic machine in Manhattan, showed that he tolerated corruption in government, while they overlooked their own brands of it.

Smith carried the popular vote in each of America's ten most populous cities, an indication of the rising power of the urban areas and their new demographics.

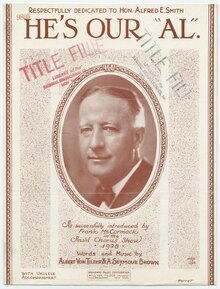

His campaign theme song, "The Sidewalks of New York", had little appeal among rural Americans, who also found his 'city' accent slightly foreign when heard on radio.

Smith narrowly lost his home state; New York's electors were biased in favor of rural upstate and largely Protestant districts.

[35] One political scientist said, "...not until 1928, with the nomination of Al Smith, a northeastern reformer, did Democrats make gains among the urban, blue-collar and Catholic voters who were later to become core components of the New Deal coalition and break the pattern of minimal class polarization that had characterized the Fourth Party System.

"[36] However, historian Allan Lichtman's quantitative analysis suggests that the 1928 results were based largely on religion and are not a useful barometer of the voting patterns of the New Deal era.

[38] Hoover sought "Southern Strategy" for the election, and sided with the segregationist lily-white Republicans at the expense of the pro-civil rights black and tans.

[40] According to Phylon, apart from the Catholics' perceived allegiance to the Pope over the United States, American anti-Catholicism was also racially motivated, as Southern Protestants "strongly opposed the church's liberal policies—particularly its uncompromising position against social and political segregation.

"[40] Al Smith was supportive of racial equality and appointed African Americans to the New York City school system and civil service commission.

"[39] Smith attracted the attention of disheartened African-American voters, as he was unpopular in the South, faced prejudice as a Roman Catholic, and had a reputation of a "spokesman for ethnic minorities in Northern cities".

[39] As such, Smith's candidacy, coupled with Hoover's Southern concession, initiated abandonment of loyalty to the Republicans and embrace of the Democratic Party by African-American voters.

After losing the nomination, Smith eventually campaigned for Roosevelt in 1932, giving a particularly important speech on behalf of the Democratic nominee at Boston on October 27 in which he "pulled out all the stops".

[43] Smith became highly critical of Roosevelt's New Deal policies, which he deemed a betrayal of good-government progressive ideals and ran counter to the goal of close cooperation with business.

[54] Knowing his fondness for animals, in 1934 Robert Moses made Al Smith the Honorary Night Zookeeper of the newly renovated Central Park Zoo.