Alabama Legislature

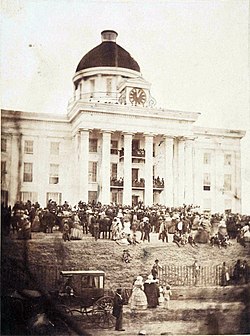

Between February and May 1861, Montgomery served as the Confederacy's capital, where Alabama state officials let members of the new Southern federal government make use of its offices.

The Provisional Confederate Congress met for three months inside the General Assembly's chambers at the Alabama State Capitol.

However, following complaints from Southerners over Montgomery's uncomfortable conditions and, more importantly, following Virginia's entry into the Confederacy, the Confederate government moved to Richmond in May 1861.

Following the Confederacy's defeat in 1865, the state government underwent a transformation following emancipation of enslaved African Americans, and constitutional amendments to grant them citizenship and voting rights.

Republicans were elected to the state governorship and dominated the General Assembly; more than eighty percent of the members were white.

The biracial legislature passed a new constitution in 1868, establishing public education for the first time, as well as institutions such as orphanages and hospitals to care for all the citizens of the state.

Elections were surrounded by violence as paramilitary groups aligned with the Democrats worked to suppress black Republican voting.

Both the resulting 1875 and 1901 constitutions disenfranchised African-Americans, and the 1901 also adversely affected thousands of poor White Americans, by erecting barriers to voter registration.

Late in the 19th century, a Populist-Republican coalition had gained three congressional seats from Alabama and some influence in the state legislature.

They passed a new constitution in 1901 that disenfranchised most African-Americans and tens of thousands of poor White Americans, excluding them from the political system for decades into the late 20th century.

The Democratic-dominated legislature passed Jim Crow laws creating legal segregation and second-class status for African-Americans.

Following World War II, the state capital was a site of important civil rights movement activities.

She and other African-American residents conducted the more than year-long Montgomery bus boycott to end discriminatory practices on the buses, 80% of whose passengers were African Americans.

Martin Luther King Jr., a new pastor in the city who led the movement, gained national and international prominence from these events.

Throughout the late 1950s and into the 1960s, the Alabama Legislature and a series of succeeding segregationist governors massively resisted school integration and demands of social justice by civil rights protesters.

Mirroring Mississippi's similarly named authority, the commission used taxpayer dollars to function as a state intelligence agency: it spied on Alabama residents suspected of sympathizing with the civil rights movement (and classified large groups of people, such as teachers, as potential threats).

When this ruling was finally implemented in Alabama by court order in 1972, it resulted in the districts including major industrial cities gaining more seats in the legislature.

[citation needed] In May 2007, the Alabama Legislature officially apologized for slavery, making it the fourth Deep South state to do so.

Because the Alabama legislature has kept control of most counties, authorizing home rule for only a few, it passes numerous laws and amendments that deal only with county-level issues.

Due to the suppression of black voters after Reconstruction, and especially after passage of the 1901 disenfranchising constitution, most African-Americans and tens of thousands of poor White Americans were excluded from voting for decades.

[3][4] After Reconstruction ended no African-Americans served in the Alabama Legislature until 1970 when two black majority districts in the House elected Thomas Reed and Fred Gray.

Prior to the introduction of bills that apply to specific, named localities, the Alabama Constitution requires publication of the proposal in a newspaper in the counties to be affected.

The Constitution of Alabama states that no bill may be enacted into law until it has been referred to, acted upon by, and returned from, a standing committee in each house.

The regular calendar is a list of bills that have been favorably reported from committee and are ready for consideration by the membership of the entire house.

It may concur in the amendment by the adoption of a motion to that effect; then the bill, having been passed by both houses in identical form, is ready for enrollment.

The "enrolled" copy is the official bill, which, after it becomes law, is kept by the Secretary of State for reference in the event of any dispute as to its exact language.

From this point, the bill becomes an act, and remains the law of the state unless repealed by legislative action, or overturned by a court decision.

The bill is then reconsidered, and if a simple majority of the members of both houses agrees to the proposed executive amendments, it is returned to the governor, as he revised it, for his signature.

If the governor fails to return a bill to the legislative house in which it originated within six days after it was presented (including Sundays), it becomes a law without their signature.

It is then submitted to voters at an election held not less than three months after the adjournment of the session in which state lawmakers proposed the amendment.