Alaric I

According to Jordanes, a 6th-century Roman bureaucrat of Gothic origin—who later turned his hand to history—Alaric was born on Peuce Island at the mouth of the Danube Delta in present-day Romania and belonged to the noble Balti dynasty of the Thervingian Goths.

[3][a] Historian Douglas Boin does not make such an unequivocal assessment about Alaric's Gothic heritage and instead claims he came from either the Thervingi or the Greuthung tribes.

"[7][b] Alaric's childhood in the Balkans, where the Goths had settled by way of an agreement with Theodosius, was spent in the company of veterans who had fought at the Battle of Adrianople in 378,[c] during which they had annihilated much of the Eastern army and killed Emperor Valens.

[12] For several subsequent decades, many Goths like Alaric were "called up into regular units of the eastern field army" while others served as auxiliaries in campaigns led by Theodosius against the western usurpers Magnus Maximus and Eugenius.

[18] Despite sacrificing around 10,000 of his men, who had been victims of Theodosius' callous tactical decision to overwhelm the enemies' front lines using Gothic foederati,[19] Alaric received little recognition from the emperor.

[22] Refused the reward he expected, which included a promotion to the position of magister militum and command of regular Roman units, Alaric mutinied and began to march against Constantinople.

[25][26] According to historian Peter Heather, it is not entirely clear in the sources if Alaric rose to prominence at the time the Goths revolted following Theodosius's death, or if he had already risen within his tribe as early as the war against Eugenius.

[25] Historian Thomas Burns's interpretation is that Alaric and his men were recruited by Rufinus's Eastern regime in Constantinople, and sent to Thessaly to stave off Stilicho's threat.

On arrival, Gainas murdered Rufinus, and was appointed magister militum for Thrace by Eutropius, the new supreme minister and the only eunuch consul of Rome, who, Zosimus claims, controlled Arcadius "as if he were a sheep".

[g] A poem by Synesius advises Arcadius to display manliness and remove a "skin-clad savage" (probably referring to Alaric) from the councils of power and his barbarians from the Roman army.

This administrative change removed Alaric's Roman rank and his entitlement to legal provisioning for his men, leaving his army—the only significant force in the ravaged Balkans—as a problem for Stilicho.

[48] Using Claudian as his source, historian Guy Halsall reports that Alaric's attack actually began in late 401, but since Stilicho was in Raetia "dealing with frontier issues" the two did not first confront one another in Italy until 402.

[49] Alaric's entry into Italy followed the route identified in the poetry of Claudian, as he crossed the peninsula's Alpine frontier near the city of Aquileia.

Kulikowski explains this confusing, if not outright conciliatory behavior by stating, "given Stilicho's cold war with Constantinople, it would have been foolish to destroy as biddable and violent a potential weapon as Alaric might well prove to be".

[58] Although the imperial government was struggling to muster enough troops to contain these barbarian invasions, Stilicho managed to stifle the threat posed by the tribes under Radagaisus, when the latter split his forces into three separate groups.

[60] Sometime in 406 and into 407, more large groups of barbarians, consisting primarily of Vandals, Sueves and Alans, crossed the Rhine into Gaul while about the same time a rebellion occurred in Britain.

During this crisis in 407, Alaric again marched on Italy, taking a position in Noricum (modern Austria), where he demanded a sum of 4,000 pounds of gold to buy off another full-scale invasion.

[65] In the East, Arcadius died on 1 May 408 and was replaced by his son Theodosius II; Stilicho seems to have planned to march to Constantinople, and to install there a regime loyal to himself.

[73] As a declared 'enemy of the emperor', Alaric was denied the legitimacy that he needed to collect taxes and hold cities without large garrisons, which he could not afford to detach.

[75] He moved across the Julian Alps into Italy, probably using the route and supplies arranged for him by Stilicho,[76] bypassing the imperial court in Ravenna which was protected by widespread marshland and had a port, and in September 408 he menaced the city of Rome, imposing a strict blockade.

When the ambassadors of the Senate, entreating for peace, tried to intimidate him with hints of what the despairing citizens might accomplish, he laughed and gave his celebrated answer: "The thicker the hay, the easier mowed!"

[79] Fearing for his safety, Honorius made preparations to flee to Ravenna when ships carrying 4,000 troops arrived from Constantinople, restoring his resolve.

[57] Why Sarus, who had been in imperial service for years under Stilicho, acted at this moment remains a mystery, but Alaric interpreted this attack as directed by Ravenna and as bad faith from Honorius.

[81]Still, the importance of Alaric cannot be "overestimated" according to Halsall, since he had desired and obtained a Roman command even though he was a barbarian; his real misfortune was being caught between the rivalry of the Eastern and Western empires and their court intrigue.

[89]Whether Alaric's forces wrought the level of destruction described by Procopius or not cannot be known, but evidence speaks to a significant population decrease, as the number of people on the food dole dropped from 800,000 in 408 to 500,000 by 419.

[91] Lamenting Rome's capture, famed Christian theologian Jerome, wrote how "day and night" he could not stop thinking of everyone's safety, and moreover, how Alaric had extinguished "the bright light of all the world.

[93] Not only had Rome's sack been a significant blow to the Roman people's morale, they had also endured two years' worth of trauma brought about by fear, hunger (due to blockades), and illness.

[94] However, the Goths were not long in the city of Rome, as only three days after the sack, Alaric marched his men south to Campania, from where he intended to sail to Sicily—probably to obtain grain and other supplies—when a storm destroyed his fleet.

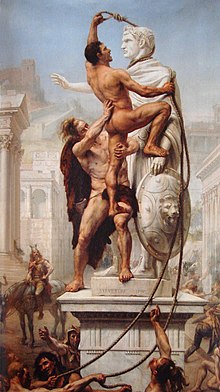

When the work was finished, the river was turned back into its usual channel and the captives by whose hands the labour had been accomplished were put to death that none might learn their secret.

[101] Not long after Alaric's exploits in Rome and Athaulf's settlement in Aquitaine, there is a "rapid emergence of Germanic barbarian groups in the West" who begin controlling many western provinces.