Alaska Statehood Act

The law was the culmination of a multi-decade effort by many prominent Alaskans, including Bartlett, Ernest Gruening, Bill Egan, Bob Atwood, and Ted Stevens.

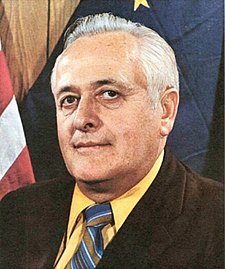

Stevens worked on masterminding the executive branch's attack, using his powerful executive office as Solicitor of the Department of the Interior, along with Interior Secretary Fred Seaton, to lobby for Alaska's statehood, placing reporters in any and all news hearings to pressure President Eisenhower & Congressmen to switch in favor of the law.

[1] Roger Ernst, Seaton's former Assistant Secretary for Public Land Management, said of Stevens: "He did all the work on statehood; he wrote 90 percent of all the speeches.

[3] Their influence spread, and they came to control the Kennecott copper mine, steamship and railroad companies, and salmon packing.

James Wickersham, however, grew increasingly concerned over the exploitation of Alaska for personal and corporate interests and took it upon himself to fight for Alaskan self-rule.

As a result of the affair, Alaska was in the national headlines, and President William Howard Taft was forced to send a message to Congress on February 2, 1912, insisting that they listen to Wickersham.

In August 1912 Congress passed the Second Organic Act, which established the Territory of Alaska with a capital at Juneau and an elected legislature.

[4] The federal government still retained much of the control over laws regarding fishing, gaming, and natural resources and the governor was also still appointed by the President.

First, he allowed for 1,000 selected farmers hurt by the depression to move to Alaska and colonize the Matanuska-Susitna Valley, being given a second chance at agricultural success.

[5] After Japan initiated the Aleutian Islands Campaign in June 1942, the territory became an important strategic military base and a key to the Pacific during the war, with a resulting population increase due to the number of American servicemen sent there.

He encouraged journalists, newspaper editors, politicians, and members of national and labor organizations to help use their positions and power to make the issue of Alaskan statehood more known.

He gathered a group of 100 prominent figures, including Eleanor Roosevelt, actor James Cagney, writers Pearl S. Buck and John Gunther, historian Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr, and theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, who all stood for the Alaskan cause.

[6] On February 27, 1952, the Senate by a one-vote margin (45-44) killed the statehood bill for another year, with Southern Democrats having threatened a filibuster to delay consideration.

The procedural move was backed by some Southern Democrats, concerned about the addition of new votes in the civil rights for blacks movement, in the hope of defeating both measures.

During this convention, Gruening gave a very powerful speech which compared Alaska's situation to the American struggle for independence.

Alaskans therefore elected to Congress Senators Ernest Gruening and William A. Egan and Representative to the House Ralph J. Rivers.

Eventually, with the help of Bartlett's influence, the Speaker of the House, Sam Rayburn, who until 1957 had been an ardent opponent of the Alaskan statehood cause, changed his mind and when Congress reconvened in January 1958, President Eisenhower fully endorsed the bill for the first time.

Senator Lyndon B. Johnson promised his commitment to the bill but others still stood in the way, such as Representative Howard W. Smith of Virginia, Chairman of the powerful Rules Committee, and Thomas Pelly of Washington State who wanted the Alaskan waters to be open to use by Washingtonians.

"[9] Debate lasted for hours within both chambers, though eventually, though, the resistance was able to be bypassed, and the House passed the statehood bill by a 210–166 vote.

[14] Hawaii statehood was expected to result in the addition of two pro-civil-rights senators from a state which would be the first to have a majority non-white population.