Alawi Sultanate

The dynasty, which remains the ruling monarchy of Morocco today, originated from the Tafilalt region and rose to power following the collapse of the Saadi Sultanate in the 17th century.

The Saadian dynasty, which ruled Morocco during the 16th century and preceded the 'Alawis, also claimed sharifian lineage and played an important role in engraining this model of political-religious legitimacy in Moroccan society.

[24][25] Known for his deep piety, he was believed to have moved to Sijilmassa in 1265 under the rule of the Marinids at the request of locals who promoted him as imam of Tafilalt and viewed the presence of sharifs in the region as beneficial for religious legitimity.

In June 1650, the leaders of Fez (or more specifically Fes el-Bali, the old city), with the support of the local Arab tribes, rejected the authority of the Dala'iyya and invited Sidi Mohammed to join them.

Soon after he arrived, however, the Dala'iyya army approached the city and the local leaders, realizing they did not have enough strength to oppose them, stopped their uprising and asked Sidi Mohammed to leave.

In July he captured Marrakesh from Abu Bakr ben Abdul Karim Al-Shabani, the son of the usurper who had ruled the city since assassinating his nephew Ahmad al-Abbas, the last Saadian sultan.

[22][21] He distinguished himself as a ruler who wished to establish a unified Moroccan state as the absolute authority in the land, independent of any particular group within Morocco – in contrast to previous dynasties which relied on certain tribes or regions as the base of their power.

In practice, he still had to rely on various groups to control outlying areas, but he nonetheless succeeded in retaking many coastal cities occupied by England and Spain and managed to enforce direct order and heavy taxation throughout his territories.

[23]: 231–232 Al-Khadr Ghaylan, a former leader in northern Morocco who fled to Algiers during Al-Rashid's advance, returned to Tetouan at the beginning of Isma'il's reign with Algerian help and led a rebellion in the north which was joined by the people of Fez.

[23]: 231–232 Meanwhile, the Ottomans supported further dissidents via Ahmad al-Dala'i, the grandson of Muhammad al-Hajj who had led the Dala'iyya to dominion over a large part of Morocco earlier that century, prior to Al-Rashid's rise.

Mawlay Isma'il besieged the city unsuccessfully in 1679, but this pressure, along with attacks from local Muslim mujahidin (also known as the "Army of the Rif"[34]), persuaded the English to evacuate Tangier in 1684.

Isma'il also allowed European countries, often through the proxy of Spanish Franciscan friars, to negotiate ransoms for the release of Christians captured by pirates or in battle.

These disturbances were compounded by drought and severe famine between 1776 and 1782 and an outbreak of plague in 1779–1780, which killed many Moroccans and forced the sultan to import wheat, reduce taxes, and distribute food and funds to locals and tribal leaders in order to alleviate the suffering.

[23]: 240 Sidi Mohammed ibn Abdallah maintained the peace in part through a relatively more decentralized regime and lighter taxes, relying instead on greater trade with Europe to make up the revenues.

After his death in 1790, his son and successor Mawlay Yazid ruled with more xenophobia and violence, punished Jewish communities, and launched an ill-fated attack against Spanish-held Ceuta in 1792 in which he was mortally wounded.

[21]: 260 Suleyman's successor, Abd al-Rahman (r. 1822–1859), tried to reinforce national unity by recruiting local elites of the country and orchestrating military campaigns designed to bolster his image as a defender of Islam against encroaching European powers.

[41]: 22 Britain's representative in Morocco, John H. Drummond Hay, pressured Abd ar-Rahman into signing the Anglo-Moroccan Treaty of 1856, which forced the sultan to remove restrictions on trade and granted special advantages to the British.

The subsequent Treaty of Wad Ras led the Moroccan government to take a massive British loan larger than its national reserves to pay off its war debt to Spain.

Hassan I called for the Madrid Conference of 1880 in response to France and Spain's abuse of the protégé system, but the result was an increased European presence in Morocco—in the form of advisors, doctors, businessmen, adventurers, and even missionaries.

[53][51] These caids were unpaid until 1856, when British consul John Drummond-Hay proposed that Sultan Mohammed IV give government workers wages from the Makhzen's treasury.

Moroccan researcher Nabil Mouline has suggested that it was adopted when Sultan al-Rashid captured Rabat, which was inhabited at the time by Andalusians who used the red flag.

[65] Inspired by Wahhabism, a crackdown on Sufi brotherhoods and mystical orders (tariqas) in the country was led by Moulay Slimane for practices he deemed to be sinful.

[19] One of the main literary genres of Morocco during this period were works devoted to describing the history of local Sufi "saints" and teachers, which were common since the 14th century.

[67]: 54, 108 During the 18th century, a number of Tachelhit poets arose including Muhammad ibn Ali al-Hawzali in Taroudant and Sidi Hammou Taleb in Moulay Brahim.

'The Plague'), and his uncle Muhammad ibn Jaqfar al-Kattani's popular Nasihat ahl al-Islam ('Advice to the People of Islam'), published in Fez in 1908, both of which called on Moroccans to unite against European encroachment.

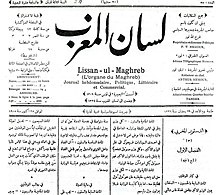

[71] During modernization attempts for the Moroccan state under Moulay Abdelhafid to counter European influence, a draft constitution was published in the October 1908 issue of newspaper Lissan-ul-Maghreb in Tangier.

[74] In 2008, al-Massae claimed that the draft was written by members of a "Moroccan Association of Unity and Progress" composed of an elite close to Moulay Abdelhafid which supported the toppling of his predecessor, Abdelaziz.

[93] Despite economic setbacks occurring periodically, civil conflicts at both national and local levels and the primitive tools employed, there remained a significant emphasis on soil exploitation and agriculture constituted the primary occupation for the majority of rural inhabitants.

[94] Pierre Tralle, a French prisoner who also participated in the construction of Meknes over a seven-year period until 1700, highlighted in his report on the Moroccan situation the fertility of the land which he considered to be adapted to producing high-quality crops.

[94] Despite opening to trade in the late 19th century, Morocco faced limitations due to inadequate agricultural surplus and the antiquated transportation system, which hindered commercial activities.